#272 Beyond McEachern’s folly

March 24th, 2018

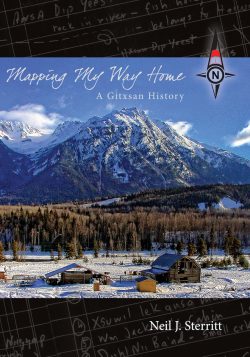

Mapping My Way Home: A Gitxsan History

by Neil J. Sterritt

Smithers: Creekstone Press, 2016

$29.95 / 9781928195023

Reviewed by Dorothy Kennedy

*

Mapping My Way Home tells the story of Gitxsan elder, geologist, and politician Neil Sterritt, who served as president of the Gitxsan-Wet’suwet’en Tribal Council in the 1980s.

Mapping My Way Home tells the story of Gitxsan elder, geologist, and politician Neil Sterritt, who served as president of the Gitxsan-Wet’suwet’en Tribal Council in the 1980s.

From 1975 to 2009, Neil Sterritt and his family lived at Temlaham Ranch, the site of a Gitxsan ancestral village on the Skeena River (a.k.a. Temlaxam or Dimlahamid), during which time he was hired as land claims director for the Gitksan-Carrier Tribal Council. A member of the House of Gitluudaahlxw, he was president of the Gitxsan-Wet’suwet’en Tribal Council from 1981 to 1987, key years leading up to the precedent-setting aboriginal rights case known as Delgamuukw v. B.C.

Between 1984 and 1991 the case known as Delgamuukw v. British Columbia made its way through the Supreme Court of British Columbia. The Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en people claimed title to over 58,000 square km of B.C.

Two Gitxsan chiefs held the hereditary name Delgamuukw during the court case: Albert Tait, who was Delgamuukw during the preparation of the trial, and Kispiox carver Earl Muldoe, who assumed the name in 1987 after Tait’s death. On the Wet’suwet’en side the chief was Alfred Joseph, whose chiefly name was Dini ze’ Gisday’wa.

In his judgment of March 1991, Chief Justice Allan McEachern dismissed the role of oral history and determined that Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en title was extinguished when B.C. joined Confederation. In his infamous judgement, McEachern opined that:

It would not be accurate to assume that even pre-contact existence in the territory was in the least bit idyllic. The plaintiffs’ ancestors had no written language, no horses or wheeled vehicles, slavery and starvation was not uncommon, wars with neighbouring peoples were common, and there is no doubt, to quote Hobbes, that aboriginal life in the territory was, at best, “nasty, brutish and short.”

The Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en appealed appealed McEachern’s ruling to the Supreme Court of Canada, which ruled in 1997 that the B.C. government had no right to extinguish the Indigenous peoples’ claim to their ancestral territories and that oral history was a legitimate type of evidence.

Reviewer Dorothy Kennedy concludes that, in Mapping My Way Home, Neil Sterritt “has done an exceptional job in demonstrating his people’s place and history in this province and this book will, itself, form part of the legacy of Delgamuukw.”

In Mapping My Way Home: A Gitxsan History (Creekstone 2016), Sterritt traces the history of the area at the junction of the Skeena and Bulkley Rivers, the resiliency of the First Nations residents who have maintained the villages of Gitanmaax and Hazelton, as well as his own personal story of growing up in Hazelton and helping his people fight the Delgamuukw court case. His overview stretches from the creation tales of Wiigyet to the advent of oil and gas pipeline proposals, including tales of the Madiigam Ts’uwii Aks (supernatural grizzly of the waters), the founding of Gitanmaax, Kispiox and Hagwilget and the coming of the fur traders, miners, packers, missionaries and telegraphers.

Mapping My Way Home was awarded the 2017 Roderick Haig-Brown Region Prize for the best book to contribute to the understanding and appreciation of British Columbia, an honour thoughtfully bestowed upon an author who has contributed greatly to the history of our province through contextualizing and elucidating his people’s oral history that almost thirty years ago evaded Chief Justice McEachern’s appreciation. – Ed.

*

The Delgamuukw v. British Columbia litigation in the Supreme Court of British Columbia provoked many responses and much scientific and legal discussion about the nature and reliability of oral history.

Among the most prominent anthropological and historical specialists reflecting on these questions was a collection of scientists whose criticism of the Court appeared in a special issue (Autumn 1992, vol. 95) of BC Studies, entitled Anthropology and History in the Courts. Guest Editor Bruce Miller concluded from these articles that the materials submitted to the Court by anthropologists and historians “were improperly utilized and badly understood.”

Certainly, Chief Justice Allan McEachern’s lengthy “Reasons for Judgement” of 1991 on this long and costly trial presented a large target for anthropologists whose rebuttal to his stinging dismissal of their discipline resulted in a mass outcry, along with some more solemn and private self-reflection. Subsequent court witnesses have both profited and suffered from the backlash, learning from the earlier Court’s reaction that experts, when amassing and analyzing oral histories, need to apply the tools of their profession more transparently.

The Court told us that evidence used within the restrictions of the western legal and political system, where the people-land relationships have been misrecognized by law and by policy, also requires greater attention to the historical context of the information and the recognition of conflicting stories.

Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en territorties.

If, paradoxically, Delgamuukw served anthropology well in bringing about more critical self-reflection of its methods, it served the First Nations even better by necessitating the collection of oral histories dispersed among elders and archives into a coherent story that connected a people to its homeland.

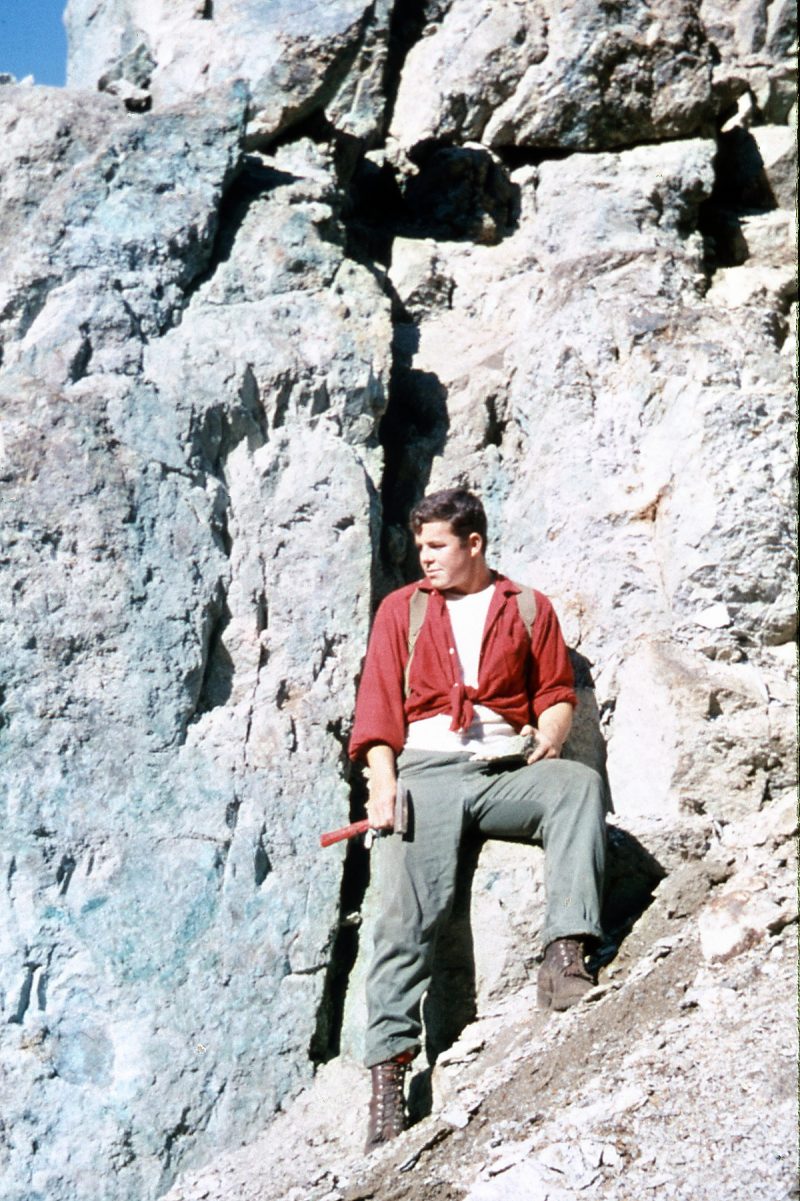

For Neil Sterritt, a member of the Gitxsan and author of Mapping My Way Home: A Gitxsan History, research undertaken in preparation for the litigation immersed him in an ancient world created at Temlaham, a place he knew as a child, left as a teenager to pursue schooling and an international career in geology, and returned to as an adult where he served as president of the Gitxsan-Wet’suwet’en Tribal Council from 1981 to 1987, key years in those communities’ preparation for Delgamuukw.

Strategy developed for the trial preparation in a series of meetings with Gitxsan-Wet’suwet’en elders between 1981 and 1984 led to the transfer of the chiefs’ knowledge of their territories onto maps and the collation of supporting documentation. The materials discussed boundaries of Houses, confirmed specific place names, and recorded descriptions of landmarks and resource use that together would present the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en chiefs’ views of their world.

Sterritt and a team of researchers spent eight years building upon earlier ethnographic studies, including Sterritt’s own mapping project begun in 1975. As Sterritt explains, “Contrary to the strategy used in the Calder case [1973] where one expert witness [anthropologist Wilson Duff] was called to prove title, our strategy was to defeat the extinguishment argument and to prove Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en title by placing a substantial body of evidence from the elders about our land, laws and oral histories against the meagre evidence of the crown and its sovereignty assertions” (p. 310).

Delgamuukw is significant, for the Supreme Court of Canada in 1997 unanimously decided that Aboriginal title consists of the right to exclusively use and occupy the land including the right to choose how the land can be used.

However, what the Gitxsan gained from the litigation was more than an impressive legal victory, for they created an archives and library that should continue to provide an enduring legacy of their people’s history from the mythical time of Temlaham through to their people’s role in Canada’s recognition of landmark legal principles.

For Neil Sterritt, what emerged from his preparation for the litigation was a deeper comprehension of his homeland. In Mapping My Way Home, it is through Sterritt’s integration of the many forms of evidence compiled for the trial that the people-land relationships of the Gitxsan become clearly apparent.

His skilful weaving together of his personal journey of discovery with the accounts of ancestors and elders, coupled with historical and resource-use maps, and with the histories of both the local settler and Indigenous communities along with that of his Newfoundland mother, provides a more familiar and accessible route towards understanding the Gitxsan-Wet’suwet’en and their territories than any of the documents alone.

With such a volume of materials to draw from, including numerous expert reports, Sterritt’s book is at times dense; at 354 pages it is far-reaching. But Sterritt has selected and told his story well. He has done an exceptional job in demonstrating his people’s place and history in this province. This book will, itself, form part of the legacy of Delgamuukw.

A Smithers court clerk receives the writ and statement of claim from the Gitxsan Wet’suwet’en Tribal Council in 1984. L-R Misilos, Delgamuukw, Neil Sterritt Gisdaywa. Ian Lindsay photo.

*

Dorothy Kennedy is a consulting anthropologist, occasional university lecturer and expert witness specializing in the Indigenous cultures of British Columbia, Washington State and, most recently, Alberta and the Yukon. She completed a Doctorate from the University of Oxford in 2000, and an award-winning Master’s degree from the University of Victoria, where she has taught in the Anthropology Department and the Indigenous Education Program. For the past four decades, including two decades devoted intensively to ethnographic and linguistic fieldwork in First Nations’ communities, she has been engaged full-time in the research process, from conceptual planning and document review to issue-focused research, analysis, and reporting. She is the author or co-author (primarily with her colleague and husband, Randy Bouchard), of hundreds of reports, as well as numerous published articles and books, both scientific and popular, including four articles in the Plateau and Northwest Coast volumes of the Smithsonian Institution’s Handbook of North American Indians and, most-recently, Talonbooks’ The Lil’wat World of Charlie Mack (2010). Kennedy and Bouchard are also editors of the well-acclaimed Indian Myths and Legends from the North-Pacific Coast of America, a translation of Franz Boas’s first and significant collection of B.C. First Nations’ mythology published by Talonbooks in 2002, and originally published in German in 1895. As of 2018, she was with Bouchard & Kennedy Research Consultants at Mill Bay, B.C.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Roy Vickers, Art Sterritt, Walter Harris , Earl Muldoe and Neil Sterritt at the opening of the carved Ksan doors at UBC Museum of Anthropology, 1976.

Leave a Reply