#78 Bud Osborn

January 26th, 2016

LOCATION: Insite Supervised Injection Site, 139 East Hastings Street, Vancouver

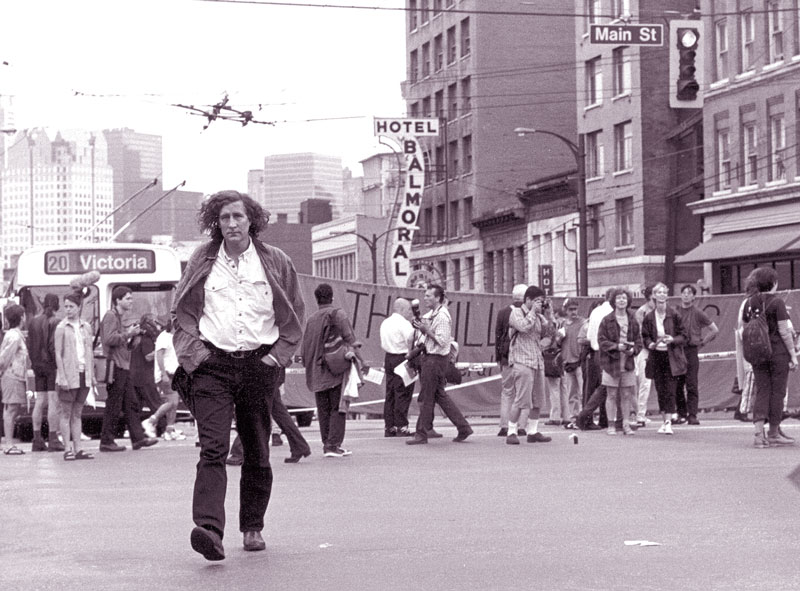

Downtown Eastside activist Bud Osborn was an originator of North America’s first supervised injection site here, near Hastings and Main. Also a superb poet, Osborn published six books, made a music CD and won the City of Vancouver Book Award. Also a co-founder of VANDU (Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users), Osborn was an unofficial archivist of Canada’s poorest neighbourhood and its most eloquent and forceful spokesman. “He could communicate with people,” said his friend and colleague, MP Libby Davies, “and he always spoke the truth, always. He never shied away from it. I credit him with being able to change the way people perceive drug users.” Hundreds gathered outside Insite for a memorial after Bud Osborn died, at 66, on May 6, 2014.

ENTRY:

Vancouver poet and Downtown Eastside activist Bud Osborn, the unofficial archivist of Canada’s poorest neighbourhood and its most eloquent and forceful author and spokesman, died on May 6, 2014, at age 66, after being diagnosed with pneumonia. He was hospitalized for five weeks, came home for one day, then had chest pains and shortness of breath. He collapsed and was rushed to emergency, but died, according to Ann Livingston, a former partner and co-founder of VANDU (Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users).

NDP MP for Vancouver East, Libby Davies, a longtime friend, said Osborn’s passing is an enormous loss to the community and that he was a hero to the people of the DTES and the City of Vancouver overall. She added that Bud Osborn understood harm reduction and safe injection sites as important health measures and a fundamental human right. “I credit him with being able to change the way people perceive drug users,” Davies said.

Osborn’s poetry worked in tandem with his activism for people living on the street and poverty issues. “His words captured the raw horror of being abandoned, poor, cold and lonely,” says Livingston.

His second publisher, Brian Kaufman of Anvil Press, recalls: “In 1994, Bud delivered his typewritten manuscript, Lonesome Monsters, to the Anvil offices on the second floor of the Lee Building at Main and Broadway. And what I saw in Bud’s work then was the same thing I see now when I open one of his books: raw, brave, human, unadorned depictions of people caught in the meat-grinder life of poverty, homelessness, addiction, and violence. He gave voice to the many that could not put it down in words, to the many who are never listened to. The epigraph he gave me for the book was this: ‘the primary intention of my writing has been fidelity to my experience and those of the people about whom I write.’ And in that, he never wavered.”

A chapbook by Bud Osborn called Keys to the Kingdom (Get To The Point Publishing 1998) received the City of Vancouver Book Award.

“Bud was an eloquent and passionate spokesperson for the dispossessed,” said publisher Brian Lam of Arsenal Pulp Press. “As a recovering addict, he knew all too well the struggles of those who live with poverty and addiction, and dedicated his life to documenting their experiences, including his own, using the medium of poetry to move and educate others. As well, Bud was a spirited activist, a well-known figure at various demonstrations and gatherings in the Downtown Eastside, which was his literal and figurative home.”

Bud Osborn was born in Battle Creek, Michigan and raised in Toledo, Ohio. His father, a reporter for the Toledo Blade, was a shot-down bomber pilot and former prisoner of war. He received his father’s exact name, Walton Homer Osborn. His father committed suicide in jail, as a traumatized alcoholic, when Bud Osborn was three. Osborn himself tried to commit suicide with 200 Aspirins when he was 15.

“Amid our peregrinations through poverty neighborhoods, I was so afraid of my name that when a tough alley urchin gang leader in another new location asked my name, I said my name was Raymond or something, but this raggedy kid replied, ‘No, it isn’t. It’s Bud!’ And I have insisted on being called ‘Bud’ ever since.”

Osborn began to consider himself as a perpetual bud on a tree, never to bloom or come to life. He briefly attended Ohio Northern University and took a job with VISTA in Harlem as a counselor. He became a drug addict, married and had a son. His family accompanied him to Toronto, but then his wife and son left him to go to Oregon. He lived on the mean streets of Toronto, Toledo and New York until he moved to the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver where he eventually entered Detox. “I stopped running and tried to face myself,” he says.

Osborn began to consider himself as a perpetual bud on a tree, never to bloom or come to life. He briefly attended Ohio Northern University and took a job with VISTA in Harlem as a counselor. He became a drug addict, married and had a son. His family accompanied him to Toronto, but then his wife and son left him to go to Oregon. He lived on the mean streets of Toronto, Toledo and New York until he moved to the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver where he eventually entered Detox. “I stopped running and tried to face myself,” he says.

Osborn’s former life as a lost soul on the mean streets of Vancouver has been dramatized in an award-winning film called Keys to Kingdoms, made by Nathaniel Geary. He was also the subject of the 1997 documentary by director Veronica Mannix called Down Here.

A former addict who was ‘seven years clean’, Osborn became a board member of the Vancouver/Richmond Health Board, the Carnegie Centre Association Board and VANDU (Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users). In the process he began working closely with MP Libby Davies and advocating for the introduction of free injection sites.

“I realize there are not many people who can advocate from the bottom, who have lived at the bottom,” he said. As a City Council candidate for COPE, Osborn became a fierce adversary of Mayor Philip Owen and met with federal Health Minister Allan Rock. He did remarkably well at the polls for someone who could have been dismissed as a former alcholic and drug addict. Although Osborn didn’t win election, Mayor Owen reversed his stance and accepted most of the policies that Osborn and Davies had been advocating. A reunion with his son ensued after 30 years of separation. Osborn has described it as “the single most powerful experience of my life.” They met a second time but the relationship proved fractious.

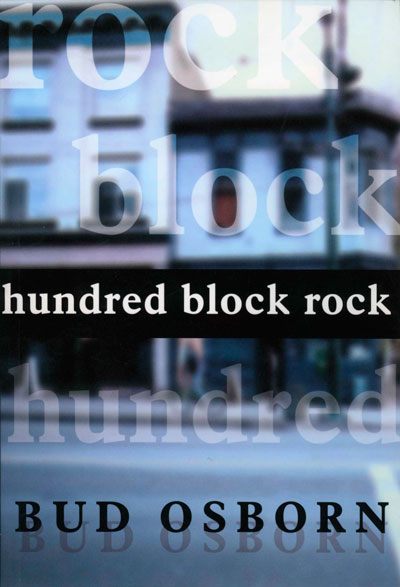

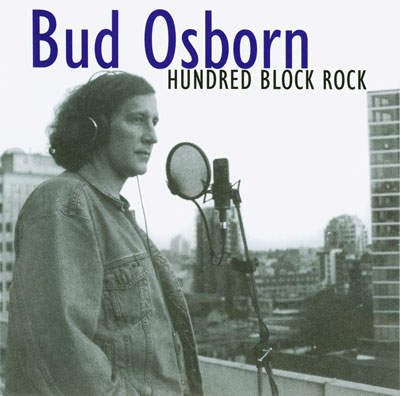

In his poetry Osborn has portrayed the ‘scorned and scapegoated’ of his neighborhood as brave souls fighting for their dignity. His collection of poetry from Arsenal Pulp and a CD of songs produced by Alan Twigg, both called Hundred Block Rock, were released to coincide with his performance at the Vancouver Folk Music Festival with bassist Wendy Atkinson and guitarist David Lester. “The title Hundred Block Rock refers to the 100 block of East Hastings,” he said, “It’s the epicentre of several pandemics. Probably the only comparable conditions are some of the worst places in the so-called Third World.”

In his third poetry collection, Oppenheimer Park (1998), with prints by Richard Tetrault, Osborn offers a plea for compassion in ‘A Thousand Crosses for Oppenheimer Park’. The long poem was spoken at a memorial service to mourn and protest the needless deaths by drug overdose of more than one thousand residents of Vancouver’s downtown eastside. “Any one of these thousand crosses could easily represent my own death,” he says. Oppenheimer Park was privately printed for subscribers. His first book was Lonesome Monsters (Anvil 1995). See Interview.

For more than twenty years Bud Osborn was also an unofficial archivist of the Downtown Eastside [DTES], Canada’s poorest neighborhood.

“We have become a community of prophets,” he wrote, “rebuking the system and speaking hope and possibility into situations of apparent impossibility.”

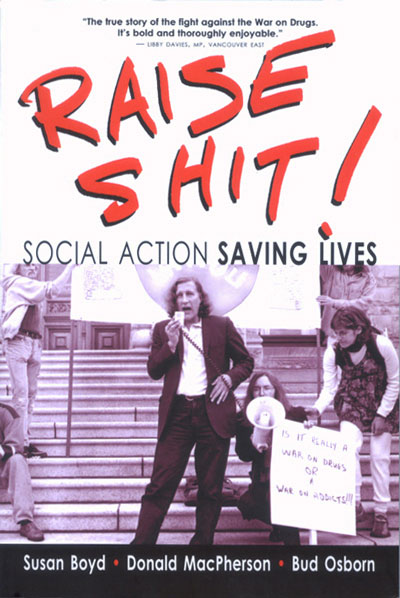

Along with Donald MacPherson, the City of Vancouver’s Drug Policy Coordinator since 2000, and UVic academic Susan Boyd—who lost her sister Diana to a drug overdose—Osborn, who ran for City Council in 1999, has documented the social justice movement in the DTES that culminated in the opening of North America’s first supervised drug injection site.

As a landmark celebration of collective activism and resistance, Raise Shit! Social Action Saving Lives (Fernwood 2009) is a sophisticated history of despair and courage, commitment and hope. It is also an important contribution to the serious literature on drug prohibition and inspiring story of how marginalized citizens have refused to let their friends’ deaths be rendered invisible.

“Our story is unique,” wrote the trio of authors. “It is told from the vantage point of drug users, those most affected by drug policy.”

The DTES made headlines around the world in 1977 when a public health emergency was declared in response to the growing rates of HIV, hepatitis C and overdose deaths among drug users in the area. At its outset, this montage of photos, news stories, Osborn poems, MP Libby Davies letters, journal entries and records of early Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users [VANDU] meetings does not fail to note: “From the early 1980s, poor women, many Aboriginal, associated with the DTES, went missing. Twenty years passed before one man was charged with the murders of 26 of the missing women; however, later he was convicted of six counts of second degree murder. The investigation is ongoing, and poor women remain vulnerable to male violence.”

Interviewed by telephone from Ottawa, Libby Davies told Georgia Straight, “He was the kind of guy, he could talk to lawyers and judges and politicians and bureaucrats, and scientists and business people…or just the ordinary person on the street,” she stated. “He could communicate with people and get them to understand what was going on, and he always spoke the truth, always. He never shied away from it.”

Keys to the Kingdom (Get To The Point Publishing 1998) by Bud Osborn received the City of Vancouver Book Award.

[For other authors pertaining to the Downtown Eastside prior to 2011, see abcbookworld entries for Atkin, John; Ballantyne, Bob; Baxter, Sheila; Brodie, Steve; Cameron, Sandy; Cameron, Stevie; Campbell, Bart; Canning-Dew, Jo-Ann; Clarkes, Lincoln; Craig, Wallace Gilby; Cran, Brad; Daniel, Barb; Douglas, Stan; Fetherling, George; Gadd, Maxine; Gilbert, Lara; Greene, Trevor; Herron, Noel; Itter, Carole; Knight, Rolf; Lukyn, Justin; Mac, Carrie; Maté, Gabor; Murakami, Sachiko; Murphy, Lorraine; Reeve, Phyllis; Robertson, Leslie A.; Robinson, Eden; Roddan, Andrew; Swanson, Jean; Taylor, Paul; Tetrault, Richard; Vries, Maggie de; With, Cathleen.]

Library Students at UBC created an archive (“The Bud Osborn Collection”) of Osborn’s poetry, accessible via:

http://cdm15935.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/landingpage/collection/p15935coll70

The UBC-generated collection is the result of projects conducted by students of the School of Library, Archival, and Information Studies at the University of British Columbia, developed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the class LIBR 582: Digital Images and Text Collections. The Osborn poems are accompanied by images by Richard Tetrault, and in collaboration with designers David Bircham and David Lester.

BOOKS:

Black Azure (Coach House Press 1970)

Lonesome Monsters (Anvil 1995). $10.95 1-895636-08-6.

Oppenheimer Park (1998), with prints by Richard Tetrault. 0-9683337-0-2.

Keys to the Kingdom (Vancouver: Get to the Point, 1998).

Hundred Block Rock (Arsenal Pulp) $14.95 9781551520742

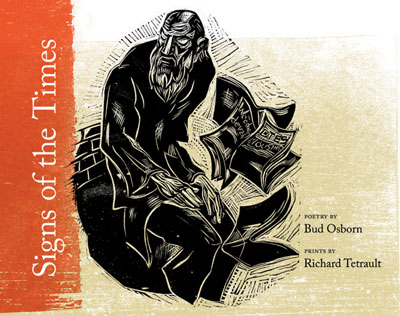

Signs of the Times (Anvil Press, Signs of the Times, 2005). with prints by Richard Tetrault.

Raise Shit! Social Action Saving Lives (Fernwood 2009), with Donald MacPherson and Susan Boyd. Non-fiction. 978-1-5526-6327-1

[Alan Twigg / BCBW 2015]

Hundred Block Rock: Interview with Bid Osborn (1999)

BW: When did you start writing?

OSBORN: In high school. I had a lot of trouble growing up, many kinds of destructive situations. I began writing on my own. Later on I found out there were poets whose lives were as messed up as mine. They seemed to understand me better than anyone in my life.

BW: Who?

OSBORN: [Arthur] Rimbaud, [Charles] Baudelaire. And I had an anthology of Beat poets. [Allen] Ginsberg’s Howl and Kaddish. Reading poems helped me get through another hour, another night, another day. I had been very suicidal until then.

BW: How close to death were you?

OSBORN: The first time I was laying, bleeding to death in a park. It was late at night, three or four in the morning, in Ohio. I was very drunk. I had fallen on my head and burst an artery. A police car went by and never even noticed me laying there. I was in the shadows, in the mud, and the blood was just pumping out of an artery in the back of my head. I figured, ‘Well, this is it.’ I remember the grass being wet, and the earth.

All of a sudden, this white Cadillac pulled to the curb, and these strong arms were lifting me to my feet. I was bleeding and muddy and drunk and they put me in this clean back seat and pressed a towel to my head and took me to the hospital. To this day I have no idea who those people were.

BW: Have there been other times when you were ‘saved’?

OSBORN: Yeah. Several.

BW: What happened to turn things around?

OSBORN: I was written off by psychologists, by cops, by judges. I was even written off by myself. I thought, “I’m not going to have a life.” It seemed foreclosed. And then something new happened in my life. One day I emerged, 45 years old, broke, homeless, in a detox centre, with nothing, and I thought, “Well, what am I going to do from here?” I decided I didn’t want to be so self-absorbed. Since then I’ve been able to contribute, to work with other people, and to passionately advocate for others. I’m still kind of stunned, going from one place to another.

BW: Where did you find the will to start working for other people?

OSBORN: I’ve thought about that. It must be somewhere in my background. My uncle organized unions in Toledo where I grew up. I remember him as being a very intense man. He fought the U.S. Army in the streets of Ohio. Strikers were killed. And my grandfather had been a coal miner. He was working in a coal mine in southern Illinois and there was a strike. Scabs were brought in from Chicago, and the miners surrounded them with rifles and opened fire. The scabs gave up, they surrendered, and the coal miners murdered 17 of them. When the coal miners were brought to trial, they were all acquitted. It would have been impossible to convict a miner in southern Illinois for the murder of a Scab.

Growing up, every kind of curse word was common currency except for the word Scab. If you said that, you were saying something really negative about somebody. That was the worst thing you could call somebody, the worst thing you could be.

BW: What about your mother and father?

BW: What about your mother and father?

OSBORN: My mother was a manic depressive and in one of her later manic phases she decided to run for president of the United States – seriously. She happened to be in a psych ward at the time. She had been in the U.S. Army. She would always end up on this ward with Vietnam vets. So one day she announced that she was going to run, and called a press conference. My mother said she was going to run on behalf of all the mental patients, all the alcoholics, the addicts, all the poor people, the Vietnam vets that were so stressed out and troubled.

BW: All the people who were right at the bottom.

OSBORN: Yes, exactly. An irony in the Downtown Eastside is that there are two hotels within a block of each other on East Hastings Street. One is the Walton; the other is the Patricia. Those are the first names of my parents; Walton and Patricia. I think about that sometimes. It’s as if there’s a family connection in terms of trying to defend people who are being assaulted down there.

BW: Do you believe in destiny? Do you have a faith?

OSBORN: I don’t know how to define theology very much, but I realize now that I don’t have the last word. Human beings don’t. We would like to, but it isn’t that way. Other factors are involved. There’s another hand involved, otherwise I wouldn’t be here. The hope of bringing possibilities out of impossibilities, that sustains me. And it sustains some of the people that I’ve met who have said, “Don’t stop. Whatever you’re doing now, just don’t stop. Don’t stop fighting.”

For instance, there has been an intense and relentless police attack on the 100-block Hastings area without taking into consideration that there are other ways to solve the problems around illicit drug use. Those are the sort of things that concern me on a day-to-day basis. That’s why it’s really exciting for me to work with musicians. It’s a way to expand the discussions beyond grinding political meetings or making speeches.

BW: Did you actually record your CD on the roof of the tall building, or is that just a promo thing?

OSBORN: No, we recorded in a studio on the roof of a building.

BW: It’s ironic to be making music on a skyscraper about life down on the street.

OSBORN: What can I say? I guess music can be celestial and down-to-earth at the same time.

BW: What happens if you get hugely successful and you wind up with tons of dough?

OSBORN: I’d buy Woodwards and develop it for the needs of the people of the Downtown Eastside.

1-55152-074-5

[BCBW AUTUMN 1999] “Interview”

The Heart of the Community (New Star $24)

Larry Loyie has also contributed to The Heart of the Community (New Star $24), edited by Paul Taylor, an anthology gleaned from the pages of the Carnegie Centre newsletter begun in 1986.With contributions from writers such as Sandy Cameron, Sheila Baxter, Maxine Gadd, Diane Wood and Bud Osborn, its appearance coincides with the 100th anniversary of the building at Main & Hastings that serves as the Carnegie Centre. 0-921586-94-9

Raise Shit! Social Action Saving Lives (Fernwood $26.95)

For almost twenty years Bud Osborn has been the unofficial archivist of Canada’s poorest neighbourhood.

“We have become a community of prophets,” writes the Downtown Eastside poet, “rebuking the system and speaking hope and possibility into situations of apparent impossibility.”

Along with City of Vancouver’s Drug Policy Coordinator Donald MacPherson and UVic academic Susan Boyd—who lost her sister Diana to a drug overdose—Osborn has documented the social justice movement that culminated in the opening of North America’s first supervised drug injection site in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (DTES).

As a landmark celebration of collective activism and resistance, the trio’s impolitely-titled Raise Shit! Social Action Saving Lives (Fernwood $26.95) is a sophisticated history of despair and courage, commitment and change.

It is also an important contribution to the serious literature on drug prohibition and an inspiring story of how marginalized citizens have refused to let their friends’ deaths be rendered invisible.

“Our story is unique,” say the trio. “It is told from the vantage point of drug users, those most affected by drug policy.”

At its outset, this montage of photos, news stories, poems by Osborn, MP Libby Davies’ letters and journal entries does not fail to note: “From the early 1980s, poor women, many Aboriginal, associated with the DTES, went missing. Twenty years passed before one man was charged with the murders of 26 of the missing women; however, later he was convicted of six counts of second degree murder. The investigation is ongoing, and poor women remain vulnerable to male violence.”

The DTES made headlines around the world in 1977 when a public health emergency was declared in response to the growing rates of HIV, hepatitis C and overdose deaths among drug users in the area.

The last time we checked, raising hell was not an official Olympic event, so as 2010 draws nearer, it will be interesting to watch how critical DTES voices will be raised.

Earlier this year anti-Olympics author Chris Shaw was hassled by the RCMP, requesting information of protest plans. 978-1-5526-6327-1

[BCBW 2009]

An Appreciation by Libby Davies: Memorial (2014)

An Appreciation by Libby Davies: Memorial (2014)

It is with a heavy heart that I write about the death of Bud Osborn. He was a true hero to a community we know as the Downtown Eastside, but far beyond that, he inspired and gave hope to our city, and many people across the country.

I knew Bud for many years and he was a dear, close friend. When times were dark and people felt hopeless; he gave us hope. When people felt they had no voice; his poetry raised many voices and gave people courage. When people yearned for belonging and community; he led by example and united people in a common cause for human dignity and respect.

Bud was such a key part in the struggle for the rights of drug users and the need for INSITE. I have no doubt, that none of the incredible changes we have seen, would have taken place had Bud not lead the way forward.

I saw the times he was exhausted, overwhelmed, and deeply concerned about lack of action by governments – but he never wavered and he never rested. How many times did he speak to us at rallies, gatherings, and events – often with a specially composed poem – so that WE could gain understanding and strength to speak out and act together.

I remember the times that people would fall silent as they listened intently to each and every word he spoke as like a prayer – and it was as though he spoke to each of us personally and deeply. Such is the impact this man had.

He influenced and persuaded, in the most honourable way, elected representatives, academics, bureaucrats, journalists, and business people to stop the madness of the so called “war on drugs”. He spoke the truth – always – and without equivocation.

Most of all though, his greatest impact was his life’s work for and with those without voice. He led by example and showed people that they could speak out, be heard and change the course of history. To the many who were marginalized, criminalized, and hopeless – he changed their lives with friendship, compassion and love.

Bud’s extraordinary work in founding groups like VANDU, is significant and lasting.

I saw Bud only a few days before he died as he prepared to leave the hospital. It amazed me that his great sense of humour was always present – even in difficult times. He was laughing softly about his experience in the hospital. We all thought he was heading home to get better. But this was not to be.

As we grieve it is Bud’s words that give us comfort:

“when eagles circle oppenheimer park

we see them

feel awe

feel joy

feel hope soar in our hearts

the eagles are symbols for the courage in our spirits for the fierce and piercing vision for justice in our souls”

amazingly alive: poem / lyrics

This BUD OSBORN poem “Amazingly Alive” is off the CD, HUNDRED BLOCK ROCK (Get To The Point Records, 1999).

here I am

amazingly alive

tried to kill myself twice

by the time I was five

sometimes it’s hard to take one more breath

inside this north american

culture of death

big big trouble

from the time I was born

lots of people get stripped

right to the bone

say nobody’s gonna

touch me anymore

if I’m gonna live

gonna be a cutthroat whore

can’t touch my heart

can’t touch my soul

yah I know all about

this north american

culture of horror

but here we are

amazingly alive

against long odds

left for dead

lazarus couldn’t have been

more shocked than me

to have been brought back

from the dead

a judge said to me

I was of no use

no use at all to society

but I got news

news for him

a society of bullshit

bullshit and greed

ain’t no damn use

ain’t no use to me

this hotshot head shrink

at a locked-up nuthouse

told me I was so

totally hopeless

so far out

and so fucked up

nothing could ever

wake my life up

but I got news for him

today

I’m so amazingly alive

I’m dancin

dancin on my own grave

had knives at my throat

thrown from a car had my back broke

gun pointed at my heart

lay bleedin to death

in a dark city park

been o.d.ed so bad make a doctor mad

lookin at me said

you’re still alive

how can that be?

said I don’t know why I’m alive except I don’t want to be

but I got news

for that doctor too

right now I’m so alive

feelin so free

doctor your science ain’t nothin

behind this

mystery

so here we are amazingly alive

against long odds

and left for dead

inside a culture teachin ten thousand ways

ways to die

before we’re dead

but here we are

amazingly alive

I used to hate it

hate

hate wakin up

say not another damn day shit make it all go away

woke up one day

wearin a straitjacket

locked in a padded cell

thought I was dead and buried

deep in hell

but today I wok up

sayin got me one more

one more day never thought I’d have before

so I’m dancin

first thing

this brand new morning

dancin first thing

to otis redding

dancin with a woman

in my arms

naked in sunshine

naked in the breeze

these arms of mine

wrapped around her

lord have mercy

her arms around me

I used to wake up

so low and mean

so down and out

wake up most days now

I say shout

shout with my heart

and shout with my eyes

shout with my balls

and shout with my feet

shout with my fingers

and shout with my soul

shout for life

more abundantly

shout for all

hard-pressed messed-with human beings

shout my last breath

shout fuck this north american culture of death

had to stop runnin

face my pain

stop killin myself

face my pain

my pain was lightning

comin down like rain

but facin me

only way I found

to start gettin free

gettin free of

north america

inside of me

gettin free of this death culture

drivin me

so here I am

here we are

amazingly alive

against long odds

left for dead

north america

tellin lies

in our head

make you feel like shit

better off dead

so most days now

I say shout

shout for joy

shout for love

shout for you

should for us

shout down this system

puts our souls in prison

say shout for life

shout with our last breath

shout fuck this north american culture of death

shout here we are

amazingly alive

against long odds

left for dead

shoutin this death culture

dancin this death culture

out of our heads

amazingly alive

OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD): Thursday, May 15, 2014

Speaker: The Honourable Andrew Scheer

Ms. Libby Davies (Vancouver East, NDP):

Mr. Speaker, Bud Osborn was an extraordinary leader and activist in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. His death has caused grief and sadness of a magnitude rarely seen.

Bud was a critical part of the struggle for the rights and dignity of drug users. He worked tirelessly for the opening of InSite. When times were dark and people felt hopeless, he gave us hope. When people felt that they had no voice, his poetry raised many voices and gave people courage. When people yearned for belonging and community, he led by example and united people in a common cause for human dignity and respect.

He worked with elected representatives, academics, journalists, and more to stop the madness of the so-called war on drugs. He spoke the truth always and without equivocation. Bud’s greatest impact was his life’s work for and with those without voice. He showed people that they could speak out, be heard, and change the course of history.

In the 100 block of East Hastings Street tomorrow, the community will unite to grieve and to celebrate the life of Bud Osborn and what he gave us.

Bud Osborn fought for human life and dignity: Obituary

by JUDY STOFFMAN, The Globe and Mail (Friday, May, 30 2014)

Tall and slender with flowing hair reminiscent of Oscar Wilde’s, Bud Osborn was a distinctive figure on Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. His people, as he put it in one of his poems, were “junkies winos hookers cripples crazies thieves welfare bums and homeless freaks” whom he saw as, above all, people entitled to life and dignity. On their behalf, Mr. Osborn fought for acceptance of the idea that addiction is an illness, not a crime.

As a young man, Mr. Osborn sank about as low as a human being could go, addicted to heroin and alcohol, shooting up, abandoning his family, living by stealing, begging, selling his blood. But around the time he turned 45, he entered a detox program in Vancouver, kicked his long-time addictions and began his second act. He became a community organizer, activist, award-winning poet and the voice of the marginalized, the outcast, the sick in Canada’s poorest neighbourhood.

When he read his poetry at bookstores, parks, or the Ovaltine Café, he seemed to fill people with hope. “When Bud read, the room went very quiet,” said Ann Livingston, his former partner.

He chronicled life on the mean streets of the Downtown Eastside (also known as DTES) in six books of passionate poetry, one of which, titled Keys to Kingdoms, won the $2,000 City of Vancouver Book Award in 1999.

“Universities and colleges have started to look at his work and realize its importance and impact,“ said Mariner Janes, a young poet who wrote his 2008 master’s thesis at Simon Fraser University about Mr. Osborn.

“He used poetry to articulate his experience,” said Brian Lam, publisher of Arsenal Pulp Press, which issued hundred block rock, another of Mr. Osborn’s poetry collections. “[DTES] was his home. He remained a prominent figure at protests and news scrums to make sure recovering addicts had a voice. He was recovered for his last 20 years. He put himself in the poetry; that was part of his recovery process.”

His greatest achievement was his leadership of the fight to open Vancouver’s controversial Insite, Canada’s first legal supervised injection site, which has steeply reduced the number of overdose deaths among the local addicts.

Mr. Osborn died in Vancouver of pneumonia on May 7 at the age of 66, and the following week 200 of his friends and fans held a tearful memorial on Hastings Street in front of Insite, marked by tributes, poetry and native drumming.

Walton Homer Osborn III was born in Battle Creek, Mich., on Aug. 4, 1947, to Patricia Osborn (née Barnes) and Walton Homer Osborn II, a Second World War bomber pilot who was shot down, captured by the Germans and interned as a prisoner of war.

Bud (an early nickname that stuck) spent his childhood in Toledo, Ohio; it was a chapter of his life marked by chaos and violence. Bud’s aunt killed her mother (Bud’s paternal grandmother) then turned the gun on herself.

His father worked as a reporter for The Toledo Blade, became an alcoholic and committed suicide in jail after an arrest when Bud was 3. He grew up in Toledo’s skid row with his mentally unstable and hard-drinking mother, who, like his father, had served in the U.S. military. Ms. Osborn picked up men and sometimes married them. “I think his mother was married seven times,” Ms. Livingston recalls. One of the husbands turned out to have been a murderer.

In his heartrending poem Four years old, Mr. Osborn recalled seeing his mother raped by a stranger whom she had brought home from a bar and being too small and weak to save her. At 15, he attempted suicide by swallowing Aspirin. At 35, he tried again, driving a car into a wall, after which he was sent to the Toledo Mental Health Centre. A psychiatrist there pronounced him “emotionally disturbed.”

There were good times, too. “Bud was a leggy 6-foot-1 and he was a runner in high school, winning races,” said his half-sister, Leslie Ottavi, who was 10 years younger, and now lives in Cary, N.C. “He was a voracious reader, he loved to read; his father left behind a lot of books. He started to write poems in high school.” He discovered Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and Allen Ginsberg’s Howl.

“I found out that there were poets whose lives were as messed up as mine,” he once said. “Reading poems helped me get through another hour, another night, another day.”

At 18 he entered Ohio Northern University, but left after two years. He married his college sweetheart, Judith, a girl from New York, but the marriage, which produced a son, Aeron, did not last.

Mr. Osborn lost touch with his son for 30 years but around the time he turned 50, he found Aeron living in Oregon. They saw each other on two occasions, but the reunion was not successful.

His sister says Mr. Osborn got into hard drugs after college, in New York, where he did odd jobs. In his poems he described scoring “smack” and selling his blood plasma to a lab, “5 dollars the first visit and 10 the second.”

He did not see heroin as a problem then, but as a solution. He later wrote that it gave him peace and was the only thing that helped him sleep.

In 1969, with the Vietnam War raging, Mr. Osborn got his draft notice and left for Toronto. His first collection of poems, Black Azure, was published there by Coach House Press in 1970.

Living hand to mouth in Toronto in a cheap hotel on Sherbourne Street, he met a woman he calls Marie in his prose-poem Gentrification, but who his friends later knew as Cuba Dwyer, a Cherokee from the hills of Oklahoma. In 1986, when he was sinking deeper into addiction, the couple moved to Vancouver and found their way to the Downtown Eastside.

Ms. Dwyer eventually became a chaplain and ministered to the AIDS-afflicted, before returning to the United States. Mr. Osborn was still a junkie and supported his habit through theft and scamming. He was eventually arrested for stealing books from the UBC bookstore.

“A judge told me I was of no use no use at all to society,” he wrote in his poem Amazingly Alive, recalling this episode:

but I got news

news for him

a society of bullshit

bullshit and greed

ain’t no damn use

ain’t no use to me

On another occasion, he was taken to St. Paul’s Hospital following a near-fatal drug overdose.

“One day I emerged, 45 years old, broke, homeless, in a detox centre, with nothing,” he told an interviewer. He decided he wanted to live, after all.

He credited his victory over heroin and alcohol to the support of a Roman Catholic priest who refused to give up on him. From then on, though born Presbyterian, he identified as a Roman Catholic. Once clean, he moved to a halfway house away from the Downtown Eastside. But he moved back after a year to a studio on Powell Street in the DTES, where he found what he called “a community of prophets.”

In the film Down Here, one of several documentaries in which he appeared, he said it was a privilege to read his poems to a crowd of poor people in a park rather than have his verses appear in a literary magazine where few would see them.

In 1997, when harm reduction was a new and misunderstood idea, he met Ann Livingston, a community organizer and mother on welfare with a disabled son. He was 49 and she was seven years younger. Ms. Livingston was part of a small group of activists who had opened an illegal supervised injection site, having read about such facilities in Spain and Switzerland. “It was called the Back Alley, and we cobbled together three tiny grants to rent a storefront and build some booths and provide clean needles, ” she recalled. “The cops visited regularly to check that no drugs were sold.“The walls of the facility were covered with poems by addicts, using the felt pens provided and someone got the idea of inviting Bud Osborn, the neighbourhood poet, to copy them down before the walls were repainted.”

The two had a decade-long relationship and became an effective duo in advocating for harm reduction. They founded the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU), which now has 2,500 members.

HIV and hepatitis C infections were then raging in the neighbourhood, due to the large number of intravenous drug users sharing needles, and this became Mr. Osborn’s chief concern when he was appointed to the Vancouver Richmond Health Board in 1998. He pushed hard – sometimes presenting his motions in poem form – for the board to declare a public-health emergency.

He wanted sites such as Back Alley made legal, and went to Ottawa to lobby. He also made the case for supervised injection sites to Mayor Philip Owen, whom he managed to meet by going to his church in affluent Shaughnessy.

“There were at least 200 people dying annually on the Downtown Eastside and this went on year after year,” Ms. Livingston recalls. Mr. Osborn and Ms. Livingston organized the installation in 1997 of 1,000 white-painted crosses in Oppenheimer Park to remember those who had died. Mr. Osborn read an inspirational poem 1,000 Crosses in Oppenheimer Park. A few years later, in 2000, they repeated the event with 2,000 crosses.

“Those were critical steps in getting governments to respond,” recalled Donald MacPherson, director of the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition, a friend of Mr. Osborn. “This was before social media – the 1,000 crosses, and 2,000 crosses. Those were significant events in the life of the city. The banner they unfurled said ‘The killing fields – federal action now.’”

With the election as mayor of former coroner Larry Campbell in 2002, the campaign for Insite picked up speed.

Ultimately, Coastal Health, the regional health authority, applied to open the facility. “Health Canada designated it as a research project; it was Health Minister Anne McLellan who approved $2-million for research,” Mr. MacPherson said.

“Bud inspired them and he pushed them; he was not to be taken lightly. He was very much about citizenship for all. He was reacting to a notion that some people didn’t count. He was trying to bring people into citizenship. That is why Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users was very important.”

After the 2003 opening of Insite, which, naturally, he celebrated by writing a poem, Mr. Osborn turned his energies to opposing gentrification of the grimy neighbourhood where he had found a reason to live. He organized against the redevelopment of the old Woodward’s building at West Cordova and Hastings Streets into expensive apartments. And he picketed last year when the upscale Asian restaurant Pidgin opened near his home. He knew there would be no room for his people in a gentrified high-rent Downtown Eastside.

Bud Osborn leaves his sister Leslie; son, Aeron; and two grandchildren he never met.

Bud Osborn (1947-2014): Obit

Vancouver poet and Downtown Eastside activist Bud Osborn, the unofficial archivist of Canada’s poorest neighbourhood and its most eloquent and forceful author and spokesman, died on May 6, 2014, at age 66, after being diagnosed with pneumonia.

Vancouver East MP Libby Davies, a longtime friend, said Osborn was a hero to the people of the DTES who understood that harm reduction and safe injection sites are important health measures and a fundamental human right. “I credit him with being able to change the way people perceive drug users,” Davies said.

Osborn’s poetry worked in tandem with his activism for people living on the street and against poverty.

His first publisher, Brian Kaufman of Anvil Press, recalls: “In 1994, Bud delivered his typewritten manuscript, Lonesome Monsters, to the Anvil offices on the second floor of the Lee Building at Main and Broadway. And what I saw in Bud’s work then was the same thing I see now when I open one of his books: raw, brave, human, unadorned depictions of people caught in the meat-grinder life of poverty, homelessness, addiction, and violence.”

A chapbook by Bud Osborn called Keys to Kingdoms (Get To The Point Publishing 1998) received the City of Vancouver Book Award.

“Bud was an eloquent and passionate spokesperson for the dispossessed,” said publisher Brian Lam of Arsenal Pulp Press. “As a recovering addict, he knew all too well the struggles of those who live with poverty and addiction, and dedicated his life to documenting their experiences, including his own, using the medium of poetry to move and educate others.”

Bud Osborn was born in Battle Creek, Michigan and raised in Toledo, Ohio. His father, a reporter for the Toledo Blade, was a Second World War bomber pilot whose plane was shot down and he became a prisoner of war. He received his father’s exact name, Walton Homer Osborn. His father committed suicide in jail, as a traumatized alcoholic, when Bud Osborn was three. Osborn himself tried to commit suicide with 200 Aspirins when he was 15.

“Amid our peregrinations through poverty neighborhoods, I was so afraid of my name that when a tough alley urchin gang leader in another new location asked my name, I said my name was Raymond or something, but this raggedy kid replied, ‘No, it isn’t. It’s Bud!’ And I have insisted on being called ‘Bud’ ever since.”

Osborn began to consider himself as a perpetual bud on a tree, never to bloom or come to life. He briefly attended Ohio Northern University and took a job with VISTA in Harlem as a counselor. He became a drug addict, married and had a son. His family accompanied him to Toronto, but then his wife and son left him to go to Oregon.

Osborn lived on the mean streets of Toronto, Toledo and New York until he moved to the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver where he eventually entered detox. “I stopped running and tried to face myself,” he says.

As a former addict who was ‘seven years clean,’ Osborn became a board member of the Vancouver/Richmond Health Board, the Carnegie Centre Association Board and VANDU (Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users). In the process he began working closely with Libby Davies and advocating for the introduction of free injection sites.

“I realize there are not many people who can advocate from the bottom, who have lived at the bottom,” he said. As a city council candidate for COPE in 1999, Osborn became a fierce adversary of Mayor Philip Owen and met with federal Health Minister Allan Rock. He did remarkably well at the polls for someone who could have been dismissed as a former alcoholic and drug addict.

Although Osborn didn’t win election, Mayor Owen reversed his stance and accepted most of the policies that Osborn and Davies had been advocating.

His collection of poetry from Arsenal Pulp and a CD of songs, both called Hundred Block Rock, were released to coincide with his performance at the Vancouver Folk Music Festival with bassist Wendy Atkinson and guitarist David Lester, followed by a cross-country tour.

A commemorative video is in the works.

“He could communicate with people,” Libby Davies told the Georgia Straight, “and get them to understand what was going on, and he always spoke the truth, always. He never shied away from it.”

Leave a Reply