#573 B.C.’s forgotten artists

July 04th, 2019

The Ormsby Review presents a joint review of all ten books in the Unheralded Artists of B.C. Series from Mother Tongue Publishing of Salt Spring Island, 2008-2017. — Ed.

- Monika Ullmann, with an introduction by Brooks Joyner, The Life and Art of David Marshall (Mother Tongue: 2008) (UABC #1)

- Eve Lazarus, Claudia Cornwall, and Wendy Newbold Patterson, with an introduction by Max Wyman, The Life and Art of Frank Molnar, Jack Hardman, & LeRoy Jensen (Mother Tongue: 2009) (UABC #2)

- Mona Fertig, with an introduction by Peter Such, The Life And Art of George Fertig (Mother Tongue: 2010) (UABC #3)

- Sheryl Salloum, with a foreword by Sherrill Grace, The Life and Art of Mildred Valley Thornton (Mother Tongue: 2011) (UABC #4)

- Christina Johnson-Dean, with an introduction by Pat Martin Bates, The Life and Art of Ina D.D. Uhthoff (Mother Tongue: 2012) (UABC #5)

- Christina Johnson-Dean, with an introduction by Kerry Mason, The Life and Art of Edythe Hembroff-Schleicher (Mother Tongue: 2013) (UABC #6)

- Adrienne Brown, with an introduction by Robert R. Reid, The Life and Art of Harry and Jessie Webb (Mother Tongue: 2014) (UABC #7)

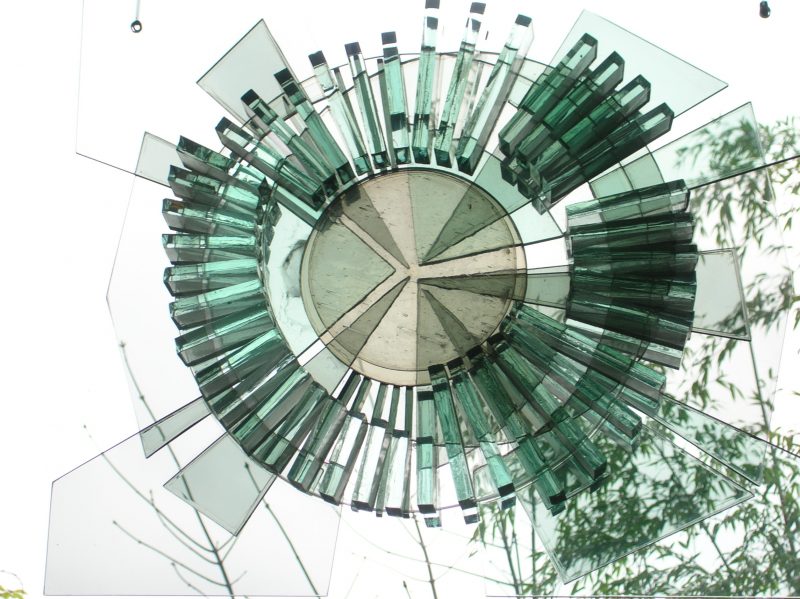

- Peter Busby, with an introduction by Paul Wolf, The Life and Art of Jack Akroyd (Mother Tongue: 2015) (UABC #8)

- Christina Johnson-Dean, with an introduction by Robert Held, The Life and Art of Mary Filer (Mother Tongue: 2016) (UABC #9)

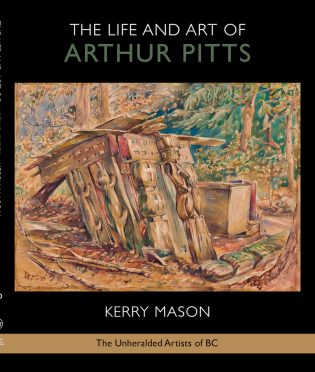

- Kerry Mason, with a foreword by Daniel Francis, The Life and Art of Arthur Pitts (Mother Tongue: 2017) (UABC #10)

All books reviewed by Nellie Lamb.

*

*

Many people dedicate their working lives to making art. Very few financially support themselves with that labour. Even fewer become household names. Statistics indicate that in Canada the average annual income for a visual artist was roughly half of that of a worker in the overall labour force. In 2010 sixty percent of artists made less than $20,000 and fifteen percent of artists operated on a financial loss. [1] I don’t have statistics for how many artists work in obscurity but it’s safe to say most do. Some artists struggle against these realities while others embrace living in the margins and even believe it is necessary to their art. One such artist, painter Jack Akroyd, wrote in a card to friends “An artist should be poor!!!!!!!” But is the financial inequity between most artists and the average worker fair? Is the work of the few artists who are widely shown and written about superior to that of the artists to those who remain in the margins of art history? What effect does the inequity of the art world have on artists? And how should we write about artists who haven’t been written about before?

The Unheralded Artists of BC, a series of ten books published between 2008 and 2017 by Mother Tongue Publishing, introduces fourteen British Columbian artists who until now have been left out of the art historical canon. The series began with owner/operator of Mother Tongue Press, Mona Fertig’s childhood memories of her father, George Fertig, a Vancouver painter interested in mysticism and Jungian psychology. Fertig became frustrated with much of the art world and felt he never received the critical acclaim or financial security he was due.

After George’s death in 1983, Mona decided to bring his work the attention it had not received during his life. The process of researching and writing about her father’s work lead her to other artists whose stories are lost to a collective “historical amnesia.” These artists became the subjects of the Unheralded Artists of BC series: David Marshall, Leroy Jensen, Frank Molnar, Mildred Valley Thorton, Leroy Jensen, Ina D.D. Unthoff, Edythe Hembroff-Schleicher, Jack Akroyd, Jack Hardman, Harry and Jessie Webb, Mary Filer, and Arthur Pitts. None had been substantially written about before. The series’ central concern is that these artists and their work deserve to be remembered. In these detailed and well-illustrated biographies, Fertig and the series’ authors try to right this perceived wrong.

Despite being an art historian, curator, art educator, and the child of artists I still don’t know how we should measure an artist’s success. Measuring it in an artist’s commitment to their work is, I suspect, an inclusive way to start; to be able to continue to make art in the face of obscurity and poverty is a significant achievement. We might also consider insight, imagination, originality, and influence on other artists. It might be that there is no single rubric for art. However, I can say unreservedly: the primary measurements of an artist’s achievements are not popularity and sales.

The Unheralded Artists series emerges from a similar perspective and suggests that devoted artists deserve attention whether or not they are able to sell or exhibit their work widely. As Sherrill Grace writes in the foreword to The Life and Art of Mildred Valley Thornton, “For every great modern artist… there are hundreds of artists who play minor roles, but who are essential to the development of the art form…” The Unheralded Artists series begins to fill in the spaces between the well-known characters of B.C.’s art history like Jack Shadbolt, BC Binning, Fred Varley, and Emily Carr and contributes to a richer body of art historical knowledge. The series adds names and details and reminds us of the breadth of artistic practice all around us. One need not travel to far away places to come into contact with serious art.

As the child of two relatively unknown artists, I am sympathetic to Fertig’s goal. I am also thankful for her work as a publisher; my introduction to Mother Tongue Press was through Claudia Cornwall’s At the World’s Edge: Curt Lang’s Vancouver, which presents Lang’s biography as a parallel to the history of Vancouver through the second half of the 20th century. I have written about Vancouver’s art of the sixties and agree with Fertig’s assertion that “there is little documented evidence of the wealth of creativity that existed before the 1970s.”

Though Vancouver is not a culture capital like New York, London, or Paris, the seventies and eighties put Vancouver on the map of cities with notable arts cultures. I believe that this expansion of artistic culture depended on the artists who were working in Vancouver in the fifties and sixties, then a provincial backwater. I believe there are too many artists whose work has gone unappreciated, and when I learned about The Unheralded Artists of BC series I found it heartening to know Fertig and the authors of the Unheralded Artists series were working to bring more of B.C.’s art history to the public’s attention.

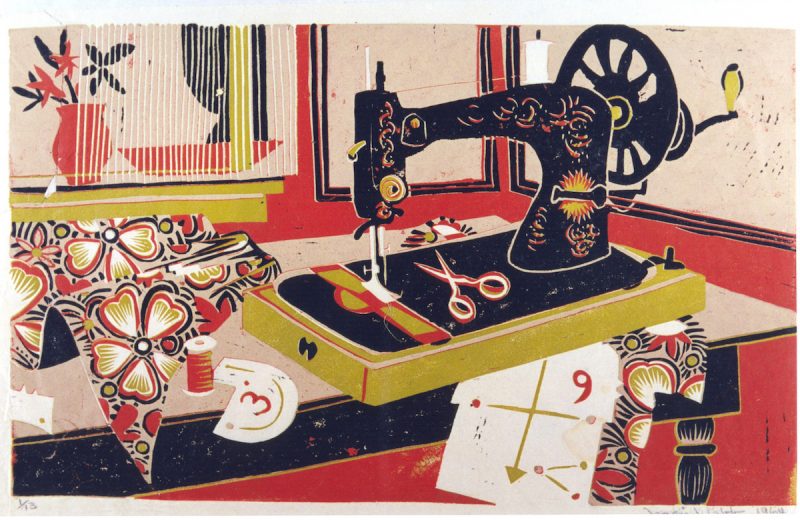

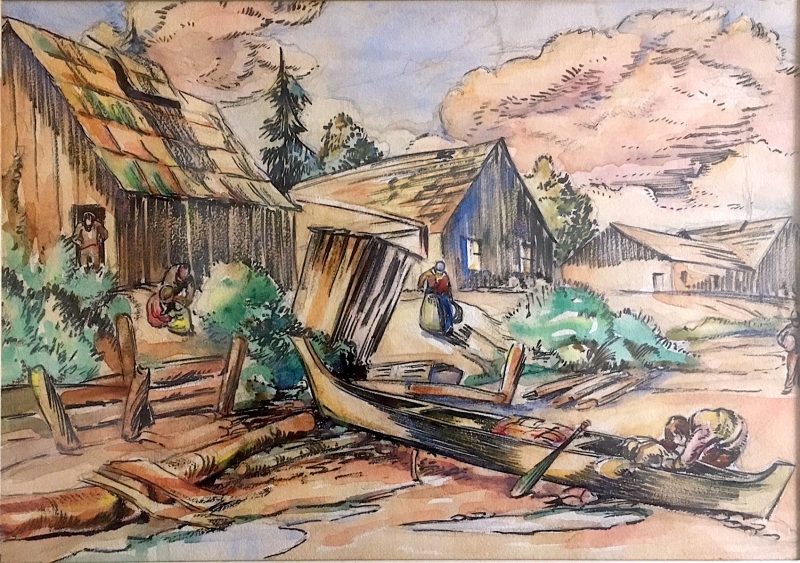

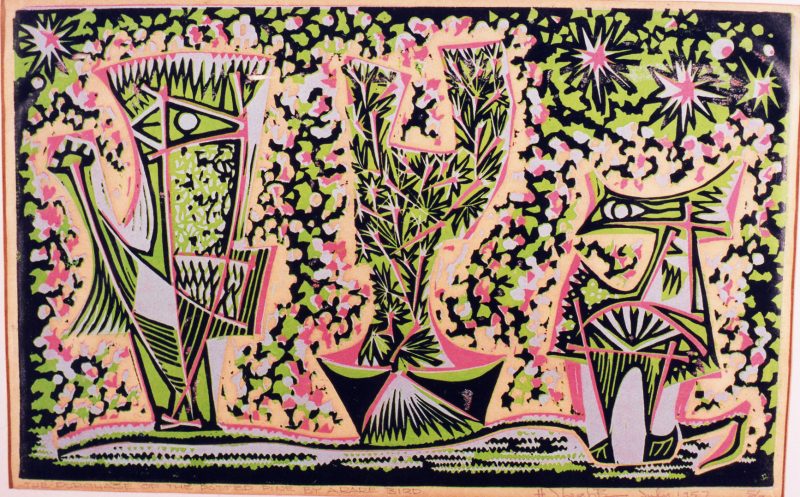

In addition to detailed accounts of the artists’ lives, the Unheralded Artists series brings high-quality reproductions of the artists’ work to the public. Each book has nearly 100 colour reproductions of artworks and photographs from the artists’ personal archives. Fertig’s instinct to feature illustrations paid off; there is a wealth of information available to readers through the images.

Several books in the series connect the excellent reproductions of the artist’s work with their biography. The work of artists like Jack Akroyd, George Fertig, Jack Hardman, and LeRoy Jensen lends itself well to biography because it is introspective and sometimes biographical itself. This is most true in the case of Akroyd’s paintings, which author Peter Busby shows are often diaristic and arranged symbolically to communicate Akroyd’s emotions. Mona Fertig connects the symbols of moon and sea in her father’s paintings to his intellectual interests in Jungian psychology, which she further ties into his personality and life story. Wendy Newbold Patterson allows the art objects to inform her biography of LeRoy Jensen and clearly articulates his artistic concerns of movement, luminosity, rhythm, and spirit.

Edythe Hembroff-Schleicher, Portrait of Emily Carr, 1971, Collection of Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Photo by Janet Dwyer

The most successful book in the series in this regard is The Life and Art of Harry and Jessie Webb, by Adrienne Brown. Brown is Harry and Jessie’s daughter and perhaps it is her familiarity that allows her to integrate descriptions and interpretations of her parents’ art into their biography from the outset. The Life and Art of Harry and Jessie Webb is engaging and makes the case for more attention for Harry and Jessie’s work, not by lamenting their lack of attention or unfurling every detail of their lives but by tying together their biographies, the themes in their work, their concerns, and their techniques so that a full picture emerges of the artists and the milieu in which they worked.

Despite the successes of some of the books, the series falls flat. Instead of making a significant addition to art history, the series fails to answer the question implied in its basic premise: what makes an artist “unheralded?” The qualifications to be in this group seem to be that no book has ever been devoted to the artist and that the artist worked primarily in B.C. in the 20th century. But that includes most artists who have ever worked in B.C. Why group these fourteen artists and not others? The qualifications for being an Unheralded Artist are never laid out, which leaves the series shallow. My guess is that these were the artists on Fertig’s radar. Just like the curators who are implicated by several authors in the series for failing to include David Marshall or Mildred Valley Thornton in their exhibitions, Fertig only had so much space in the series and chose artists who were visible to her and who she thought deserved the attention.

We need artists’ biographies to reflect both the artist and their time and the contemporary concerns of our time. In the individual books, the most glaring misunderstanding of contemporary thought appears in The Life and Art of David Marshall, in which author Monika Ullmann suggests that modernist styles are “timeless” by way of criticism of curators who by the 1960s were no longer interested in showcasing Marshall’s large modernist sculptures. This assertion is incorrect — artistic styles are always rooted in a specific socio-political time. In Marshall’s case, Ullmann misses an opportunity to link Marshall’s old-fashioned personality and “traditional” values to his artistic choices in a meaningful way.

Overall, the series doesn’t take an accurate reading of contemporary understanding of who is left out of artistic discourse both historically and today. There isn’t one artist of colour in the series though there are several artists who took Indigenous people and people of colour as their primary subjects. I am wary of tokenism but in almost any survey of artists published in the 21st century and especially a survey of lesser-known artists I expect to find stories of people of colour, people with disabilities, and LGBT2SQ+ people since these are the voices that have so often been harshly excluded from the art world (as well as many other parts of society).

If it was hard for Mother Tongue’s white men and women artists to fit into the art world, it was harder and even dangerous for many others. I imagine readers will be quick to point out that the series is evenly divided between women and men. It is, and the women’s stories were likely more difficult to research than their male counterparts; but any feminism that doesn’t include LGBT2SQ+ people, people of colour, people with disabilities, and other frequently marginalized voices is only ever masquerading as the real thing. Though I acknowledge that it is the nature of underrepresented stories to be more difficult to research and write, I cannot excuse any survey of “unheralded” artists of BC that does not include these stories.

Although the series fails to address systemic reasons an artist might be excluded and remain obscure (sexism, racism, classism, etc.), it reveals that the art world is often a cruel and traumatic place for artists no matter their social status. The pressure to continue showing, selling, and constantly advancing the style and content of one’s work to fit the fashion of the day wears on artists. For example, Monika Ullmann describes David Marshall’s lifelong defensiveness of his style of modernist sculpture, which had lost its popularity near the beginning of his career as an artist. Adrienne Brown writes that though her mother continued painting into her sixties, she increasingly avoided selling her paintings for fear of being taken advantage of. Even when an artist receives recognition and gets a show, it can be terrifying and wounding to share the work with critics, curators, and admirers who may misinterpret and misrepresent. In Jessie Webb’s case, this trepidation meant remaining “unheralded.”

Although these books bring the artists’ names, biographical details, and high-quality images of their work to the public they do little to convince me that these artists deserve careful attention, which is an unfortunate disservice to the artists. These books don’t make much of an argument either as stand-alone books or a series. They suggest that the art world should be more inclusive but they don’t really set a great example of inclusivity. They are against and outside the art world and yet their raison d’être is to include these artists in the art world. They begin to say something about the hardship of being an artist but it’s not thoroughly examined throughout the series and falls flat. The lack of an argument suggests that there really isn’t much to say about these artists other than to deliver a chronology about where they travelled, whom they married, and what jobs they took. After spending time with these books and looking at the images they hold, I believe much of the Unheralded Artists’ work deserves further research.

The inequity between most artists and the few who find recognition and financial security is heartbreaking. It doesn’t take much time in the art world to hear an artist — faced with playing the system or another rejection — say, “Maybe I’ll just give up on art.” Fertig’s attempt to address this failure of the art world is admirable. However, these books, like their subjects, are often out of touch with current concerns. The thorough biographical details and full-colour plates provide a valuable resource to someone who might want to take on a thorough art historical or curatorial project. A critical examination of these artists’ work remains an incomplete project. I hope it is a project some researcher will take up soon because there are many artists, both living and dead, several of whom are included in The Unheralded Artists of BC series, whose insight, ideas, expressions and contributions to art deserve thoughtful, critical attention and to be shared widely with art appreciators in B.C. and beyond.

*

Nellie Lamb is a curator and educator based in Coast Salish territory (Vancouver and Victoria). Her research and curatorial practice are centred in notions of place; she is currently investigating human relationships to the sea in the context of the ecological crisis. Her educational practice is also place-based and focuses on the value of practicing deep observation. Nellie graduated with a Masters of Arts from the University of Victoria’s Art History and Visual Studies program in 2018. She has curated exhibits for Integrate Arts Festival’s FUSE, the University of Victoria’s Legacy Art Galleries, and Open Space.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Kelly Hill. A Statistical Profile of Artists and Cultural Workers in Canada Based on the 2011 National Household Survey and the Labour Force Survey. Hamilton Ontario: Hill Strategies Research Inc. 2014. Accessed January 4 2019, pp. 30-33.

Leave a Reply