#538 Two belligerent short story critics

April 28th, 2019

The Canadian Short Story

by John Metcalf

Windsor, Ontario: Biblioasis, 2018

$28.95 / 9781771960847

*

Best Canadian Stories 2018

by Russell Smith (editor)

Windsor, Ontario: Biblioasis, 2018

$19.95 / 9781771962490

Both books reviewed by Paul Headrick

*

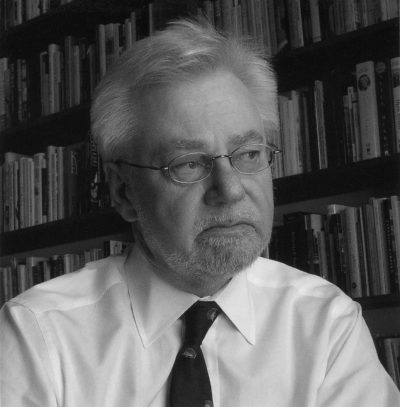

John Metcalf’s The Canadian Short Story champions fifty Canadian short story writers (about one third of whom are British Columbians). Their work, he believes, represents the best of Canadian fiction. Metcalf could be considered a hero of Canadian literature just for his crucial role in the early years of Alice Munro’s career, but the list of important anthologies he has edited and significant Canadian writers he has helped is long, and what he says about fiction matters. Though this book is important, however, it’s disappointing, and its weaknesses are bound to make Metcalf’s take less influential than it could have been.

The opening chapters re-tell the tale of the emergence of Anglo-American literary modernism in the early decades of the twentieth century. They also review the lack of response of the Canadian literary scene, which, in Metcalf’s words, merely “slumbered on.” Much of the material is familiar, the general perspective having been covered by many academics, and the Canadian material by Metcalf himself as long ago as in Kicking Against the Pricks (ECW Press, 1982 — see in particular “Editing the Best”).

Metcalf rejects the neutrality of most contemporary literary historians. For him, modernism amounted not just to a change, but a glorious revolution, sweeping away an inferior past. “Traditional writers babied readers by showing pictures and then explaining them, gently shepherding readers along in the desired direction, making sure they didn’t stray off the safety of the sidewalk” (p. 19). It seems that nothing meaningful is to be gained through an imaginative leap that places one in the position of the sort of reader implied by a nineteenth century novel. We can’t even provisionally relinquish authority and appreciate an explaining narrator without being infantilized. Nor is anything to be gained by reflecting on the reasons certain manners of narration came to feel intrusive to some readers early in the twentieth century. For Metcalf, it’s simply the case that modernist is good, pre-modernist bad. (Metcalf is so committed to the modernist sensibility that he frankly acknowledges he has difficulty appreciating pre-modernist painting.)

Metcalf subscribes to the great man theory of literary history, at least in relation to modernism, where his great man is clear: “nearly all significant writers in English derive in some aspect or another from Pound and the ideas of Imagism” (p. 41). Ezra Pound was certainly an influential publicist for the modernist cause, but an account of such a broad change in literature that emphasizes the contribution of one individual seems almost self-evidently inadequate. Over many decades now, academics have retold the story of the great shift in all the arts of the early twentieth century with more attention to complicated social factors. Pound has been displaced from his position as a guiding intellectual force. An argument that seeks to restore him to the position of preeminent cause would need to deal with that academic work in order to be convincing. Metcalf simply ignores it.

This opening section makes Metcalf’s aesthetic clear. The modernist short story is better because it shows rather than tells. Its narrators refuse to explain or guide, and its readers are more involved and fulfilled because more is demanded of them. Crucially, the stories overcome the “tyranny of plot”; they are not about what happens so much as about their own style. For Metcalf, “form and content are indivisible … the way something is being said is what is being said” (p. 16). There’s an important movement here, from asserting a kind of equivalence between form and content, to asserting that form — the way something is said — is the content. So, to read properly we must focus not on plot or character, but form, which for Metcalf means style, the story at the level of its phrases and sentences. It’s the popular and persistent demand for plot in the old sense that makes Metcalf disdainful of contemporary, novel-loving readers.

To make his argument clear, Metcalf uses the useful analogy of painters who choose to view paintings from up close, where they can see the brush strokes. Writers, similarly, see stories from up close, where they can attend to the placement of a comma, the importance of a single word, and the structure of a sentence. Metcalf wants to teach people to read as writers do. Could we shift back and forth, taking in a middle view, from where a few brush strokes become an enigmatic smile or a translucent pearl, or retreating for a moment to a more distant, academic position so as to notice broad patterns? Metcalf himself certainly does so, observing from the middle ground when he discusses character, for instance, and even entering the academic territory at the far end of the gallery, simply when he speaks of a story as modernist. But he doesn’t seem to notice what he’s up to or acknowledge the value of these different perspectives.

Among the best parts of this historical review are those in which Metcalf reflects on his own reading and writing experiences. He presents a careful analysis of Katherine Mansfield’s famous story “Miss Brill” and then offers up one of his own early efforts. His acknowledgment that he was engaged in imitation is generous; it gives permission to other writers to proceed the same way, to be unembarrassed by learning from the masters. His enthusiasm for the writers he admires had me jotting down many names and titles, composing a to-read list of Metcalf recommendations.

But as a whole, this historical review becomes tedious, weighted down in part with asides driven by Metcalf’s many deep resentments, his decades-old enemies list. He’s furious with academics, who fail to see that all of literary criticism should do what he does, which is to evaluate. He’s furious with publishers, bureaucrats, and Canadians in general for not appreciating the short story and its modernist virtuosos as they should. His anger seems to overcome him, such that he can’t see the silliness of some of his arguments. The fact that an as-new copy of an Alice Munro collection can be found in a thrift store doesn’t show how hopelessly ignorant the Canadian reading public is (it shows what happens to some copies of any books with massive print runs). Of course a passage from a terrific short story by Vancouver’s Shaena Lambert is more exciting than what we find in Northrop Frye, but that tells us nothing about Frye, or academics, or the value of what they do. (Over a few decades Frye has gone from being one of the most influential theorists of literature of the twentieth century to now being mostly ignored by academics in Can Lit and elsewhere. Metcalf’s continuing animosity to him is simply odd.)

After roughly 200 pages, we come to Metcalf’s “century list,” his discussion of the fifty Canadian authors who since 1900 have produced important short story collections. But the earliest book he includes, Mavis Gallant’s The Other Paris, was published in 1956. The early starting date, then, emphasizes Metcalf’s dismissal of most of what was written in Canada before mid-century. One point of such a list, as Metcalf acknowledges, is to stimulate a discussion. Some will advocate for contemporary writers that he’s omitted (B.C.’s Anne Fleming would be on my list, for the excellent Pool Hopping and Other Stories (Polestar) and the even better Gay Dwarves of America (Pedlar Press.)) Some will find an earlier example that they think is worthwhile – perhaps Sinclair Ross’s “Cornet at Night” (which Metcalf gave careful attention to many years ago). But with respect to when Metcalf begins his discussion, exceptions aside, well, he’s right: earlier Canadian fiction is mainly dull. Does the delay of forty-two years between Joyce’s publication of Dubliners and Gallant coming up with the first important Canadian modernist work show how terribly slow we are? Metcalf thinks so.

Eleven of the writers get extended attention, “because of the weight and presence their accumulated work has built over the years.” Five of these are British Columbians: Caroline Adderson, Cynthia Flood, Keith Fraser, Kathy Page, and Leon Rooke (Rooke spent a couple of important mid-career decades in the province). The others are Clark Blaise, Mavis Gallant, Hugh Hood, K.D. Miller, Alice Munro, and Diane Schoemperlen. Gallant and Munro are at the centre of things for Metcalf, with the work of Blaise and Norman Levine singled out as well. (Levine is omitted from Metcalf’s eleven, although more pages are devoted to him than to Fraser or Hood).

Metcalf organizes his discussions alphabetically by author, which makes this a reference work that will reward browsing more than reading straight through. As promised, he focusses on and celebrates style. He presents substantial quotations and some detailed analyses of paragraphs, sentences and phrases to show how these writers’ stories achieve their effects with finely worked details.

For example, the narrator of Vancouver author Caroline Adderson’s A History of Forgetting describes Denis, an aging hairdresser: “Despite decades of dishes laced with butter and, yes, lard, Denis had never gone to fat. Almost imperceptible, his transition from blond to grey.” Metcalf then explains: “The alliteration of the first three words embodies the repetition, the hundreds of dishes. The second sentence makes us wait for its meaning until it fades to its final ‘grey’” (p. 220). Here, and throughout much of the four hundred pages that follow, I’m convinced. Metcalf is a skilled reader, and when his analysis is this specific, it’s an informative pleasure. (Close reading of this sort was developed by academics, that crowd that Metcalf despises, initially as a technique for approaching modernist poetry, and then fiction as well.)

Among the best of these discussions are those in which Metcalf strays from his up-close focus on style to consider plot and theme. In his valuable chapter on Mavis Gallant he says that the stories in one of her masterpieces, The Pegnitz Junction, “probe what it is in us, the man in the street, as it were, that makes us culpable in the horrors of the twentieth century” (p. 355). So, a story isn’t only about its style. It can also be about something as political as twentieth century horrors without mucking around in the slums of traditional fiction.

I wish Metcalf had followed this example more often; it doesn’t do a disservice to the writers and their sophisticated styles to consider how their stories are “about” more than their form. Vancouver’s Cynthia Flood is as remarkable a stylist as Metcalf says. Would it diminish her in some way to point out that many of her stories deal with the Canadian political left, a world seldom represented elsewhere in our literature? But it seems that Metcalf wants so much for us to recognize the importance of style that he’s only rarely willing to help us appreciate the subtleties of modernist plot-making, for these stories overcome the “tyranny of plot” not by doing away with it, but by creating structures that are more sly and surprising than the traditional “tales” that they supersede.

A few of the inclusions are puzzling. Margaret Atwood makes it into the honoured fifty, but she seems to be there mainly so Metcalf can criticize her (persuasively) for her didacticism. His praise for Vancouver Island’s Jack Hodgins is grudging at best; he likes only three of Hodgins’s stories, and he is included, it seems, so that Metcalf can acknowledge his prejudice against “folksy” writing and then explain it in a way that gives the impression he thinks it’s not a prejudice at all, but reasoned judgment. (Many of the examples of humour that Metcalf admires are derisive, at the expense of characters who lack urban sophistication.) Some of the exclusions are eyebrow-raising as well. Not one Indigenous author makes it over the bar. The Metcalf century list is so overwhelmingly white that it feels pointed, as though he’s waving a banner to proclaim his indifference to political correctness. There are no translations of Canadians who write in French, and also no qualifying acknowledgment that his consideration of Canadian fiction is limited linguistically. Metcalf is hostile to all nationalism, and clearly to Quebec nationalism, and again, the unacknowledged omission feels pointed.

A consequence of these weaknesses, I’m sorry to say, is that I doubt the book will be very widely read. Its intelligent admiration for the selected writers is infectious, but that positive spirit is undone by all the self-righteousness, the griping, the spoiling for a fight. It’s as though Metcalf had to choose between becoming even more influential than he has been, with a career-capping, definitive, informative and accessible treatment of the Canadian story, or indulging his anger and revelling in the position of the angry but superior minority. He picked the latter, and much of the result is just boring.

*

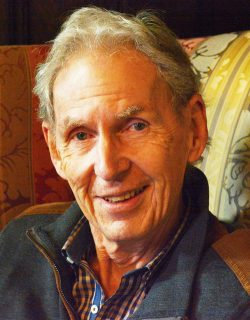

Over many years one of the services that Metcalf has done Canadian literature is to have edited Best Canadian Short Stories. For the 2018 edition, however, that task has been taken on by Russell Smith (one of the fifty on Metcalf’s century list). In his introduction to the anthology, Smith shows that he’s firmly in the angry Metcalf camp. Smith is irritated by people who are too clueless to distinguish fiction from non-fiction, by intellectuals who read fiction with a politically correct reductiveness, and of course by academics. (He quotes Metcalf complaining about a group of academics who did not understand Hemingway the way he should be understood.) In sum, says Smith, “People don’t really get what fiction is for” (p. 12). He styles the anthology as his explanation: the stories tell us what stories are really for.

But who are Smith’s imagined readers? Does he think that people who have stupid ideas about stories will buy this book, read the introduction, then read the stories to learn where they have gone wrong? It’s an obviously self-sabotaging rhetorical strategy, an extension of the belligerence that undermines Metcalf’s book. Even when Smith’s introduction goes on to discuss the stories themselves, his resentment intrudes. In a way that overlaps with Metcalf’s aversion to “folksiness,” Smith wonders why there has been “so much published fiction about the unemployed and illiterate in this highly educated nation” and says “I am actually surprised we don’t have a named genre for fiction that deals with graduate students pretending to be fishermen” (p. 15). Many readers are in the habit of skipping introductions of this sort, and Smith will be fortunate if that holds true here.

The stories themselves are good, and thoroughly modernist. Metcalf discusses the way in which the modernist story has developed a structure that threatens to become predictable and even rigid – the “epiphany story” that progresses toward a moment of heightened awareness for the protagonist. With Smith’s selections, we find a variety of writers resisting that predictability. Tom Thor Buchanan’s “A Dozen Stomachs” is a story in twelve sections, each one describing the experience of a stomach. Lynn Coady’s “Someone is Recording” gives us one side only of an email correspondence. Reg Johanson’s “A Titan Bearing Away Many a Legitimate Grievance” is mostly stream-of-consciousness, which isn’t a new technique, of course, but still feels challenging. Yet in each of these stories, plot still exerts its tyrannical force; the stories’ successes depend on their plots being deeply buried, still generating tension and moving things along for the attentive reader.

The most striking of these efforts to make the modernist story new again is “Twinkle, Twinkle,” by Stephen Marche. It’s science fiction, with a delightfully geeky metafictional twist. Marche claims to be writing the story according to a computer-generated algorithm derived from an analysis of multiple examples of the genre. In a series of footnotes, Marche tracks his efforts to conform to the algorithm’s dictates. The main character observes life on a distant planet, and the drama she witnesses forms a plot of its own, while the way that drama affects her forms another. Yet another plot line, really the most interesting one, is created by the footnotes: the story is about the author’s struggle to meet the algorithm’s demands while still writing effectively. The best moment occurs when we come to an awkward description and recognize it as an insertion required to conform to the algorithm. It’s a flaw in the story of the main character and her disappointing life, but it’s a charming success in the story of the writer and his grappling with the bossy sci-fi formula.

More conventional in its structure, for interesting reasons, is Bill Gaston’s “Klint.” The narrator is a struggling young man, self-exiled to a remote fish farm on Vancouver Island’s west coast. As the disruptive title character enters the scene and the mysterious conflict begins to clarify, we see that the story is most emphatically about something other than its form. It’s about the ecological disaster we’re inflicting on the planet. The story is moving, and in its clear attention to the most urgent of issues it reminded me of Kathy Page’s remarkable “We, the Trees,” from Paradise & Elsewhere (Biblioasis).

As the effects of climate change increase, will we see more work like this? Will the modernist short story that Metcalf and Smith and many of us admire so deeply come to seem involuted, rarified — unforgivably dated when sea levels are rising and smoke fills the skies?

*

Paul Headrick is the author of a novel, That Tune Clutches My Heart (Gaspereau Press, 2008; finalist for the BC Book Prize for Fiction), and a collection of short stories, The Doctrine of Affections (Freehand Books, 2010; finalist for the Alberta Book Award for Trade Fiction). He has also published a textbook, A Method for Writing Essays about Literature (Thomas Nelson, 2009; 3rd edition 2016). Paul has an M.A. in Creative Writing and a Ph.D. in English Literature. He taught creative writing for many years at Langara College and gave workshops at writers’ festivals from Denman Island to San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. Recently he was a mentor for the graduate fiction workshop in The Writer’s Studio at SFU.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply