#525 Ron Holland makes a splash

April 06th, 2019

All the Oceans: Designing by the Seat of My Pants

by Ron Holland, with a Foreword by Rupert Murdoch

Vancouver: Ron Holland Design 2018, distributed in Canada by Georgetown Publications

$45.00 / 9781775096801

Reviewed by Marianne Scott

*

Eminent yacht designer Ron Holland, born in Aukland, New Zealand, in 1947, moved to San Francisco in 1969, to Ireland in 1973, and to Vancouver in 2012. He has now written a memoir of his international career, All the Oceans: Designing by the Seat of My Pants.

“Yacht racers, yacht designers, and many who love the wind in their sails will enjoy this memoir,” writes Ormsby reviewer Marianne Scott of Victoria.

On April 5, 2019, Ron Holland’s All The Oceans was named a 2018 finalist in the 21st annual Foreword Magazine INDIES Book of the Year Awards. The winners will be announced June 14. — Ed.

*

“Really not much in my life was planned. It was saying ‘YES’ to the next opportunity.”

“Really not much in my life was planned. It was saying ‘YES’ to the next opportunity.”

This is how Ronald John Holland encapsulates his life in his autobiography All the Oceans: Designing by the Seat of My Pants. He tells the story of how he became an internationally renowned yacht designer in an engaging and straightforward way, as if he’s having a cup of tea or a few slow beers with the reader. Without rhetorical flourishes, he puts you aboard with him while he’s recalling the quarter ton race on the Solent that lies between Southampton and the Isle of Wight. When the wind dies, the boat is in sixth place and the yacht just drifts around, you share the disappointment.

What strikes you right away in this memoir is Ron’s prodigious memory of every boat he has sailed, raced, designed, built, or capsized from the smallest dinghy to the most luxurious megayacht. He’ll regale you with a sailboat race that took place decades ago, with precise descriptions of the gale, the nearby rocks, how he gripped the wheel, tacked, gybed, raised and lowered the spinnaker, and pushed the limits of his boat. Moreover, he describes the tactics of the boats he’s racing against. He even recounts what his teammates said, reconstructing the dialogue.

Ron Holland’s Flying Ant racing skiff (left) on Waiaki Beach, Torbay, New Zealand, circa 1958. Ron Holland photo

Ron’s path from humble beginnings to international recognition is improbable. Today, many career tracks require advanced degrees, certifications, apprenticeships, captain’s tickets. Ron found success despite being a high school dropout. He was born in Auckland, New Zealand, in 1947. His parents’ income was extremely modest, but from the beginning, they supported his desire to be on the water. For his seventh birthday, he was presented with a sailing dinghy. Ron writes he was disappointed — he’d wanted a rowboat. Still, after a tryout of the P class snub-nosed dinghy with his dad, which capsized with Ron plunging into the water screaming for his mother, he was hooked on sailing. That love of having the wind lift a boat speedily across salt water grew into a near obsession that has not waned.

Sociology professor Morris Massey developed the theory that the experiences of our early years imprint and shape most of the rest of our lives, coining the phrase, “What you are is where you were when you were ten.” Ron appears to embody the “Rule of Ten.” At age 11, he was out sailing solo on Hauraki Gulf in his next dinghy, the 12-foot Flying Ant, Tempo. The wind died and it grew dark. Adrift and fearful of being run over by large ships, he eventually realized he could paddle home. He reached shore after midnight, exhausted, having focused on the flashlight his mother had used to signal from the beach. It being the late 1950s, he didn’t even get scolded. (Would today’s parents who drive their pre-teens to school in a SUV understand that kind of autonomy?)

Ron Holland in the UK with his airplane and his Renault. “When you own a big twin engine plane you can’t afford a fancy car,” he writes in All the Oceans. Photo by Michael Levitt, Nautical Quarterly (August 1980)

From this frightening event, Ron learned a lesson, even if only subconsciously: If one way of doing things doesn’t work, try another — a concept he used throughout his career, forever improving his designs.

Ron’s parents and younger brother Philip also caught the sailing bug. Weekends were spent at the Torbay Boating Club, which sounds grander that it was. Ron calls it “the crucible of my lifelong career in sailboats.” It was a place where boats were pushed from the beach into the water and volunteer judges hung out in a tent. And it was the beginning of a long apprenticeship on how to tack and gybe, tune a rig, and play the winds. He learned about seamanship and the written rules of sailing. Moreover, he came to understand the informal code of sailing, or what he explains as, “the ethos of fairness — and good behaviour — which is understood right around the world.”

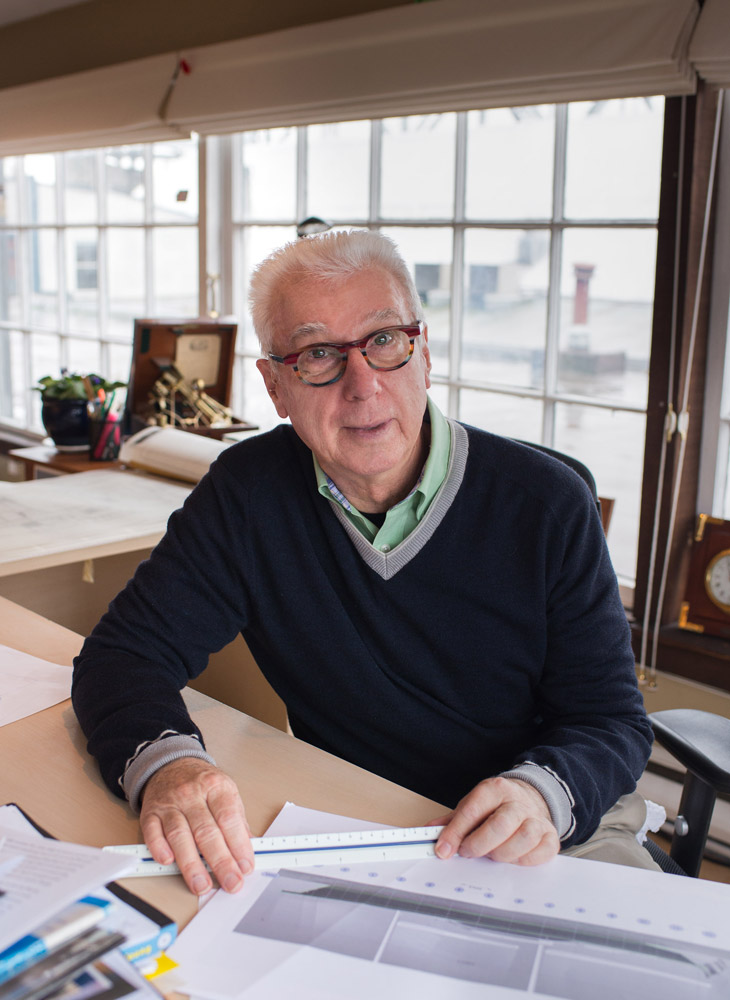

Ron Holland at work, 1990s. Creating yacht designs required the use of drawing splines, wood, or plastic held in place with dead weights. Photo by Andrew Bradley

The first New Zealand challenge for the America’s Cup, 1987, in the Indian Ocean off Western Australia

Meantime, Ron was unhappy in school. Reading was a huge obstacle, until his worried mother asked Marie Clay to teach him reading after school. The teacher recognized Ron’s interest in all things nautical, and they started reading books about Captain Cook, whom Ron venerated. Other sailing adventures were also on the reading menu, and soon Ron became a much improved reader (a good lesson to remember for kids with reading problems).

He found school boring. After failing to complete his School Certificate test twice — bookkeeping did him in — Ron scooted to the dock to see if any new boats had arrived. He never returned to school and, at age sixteen, began an apprenticeship in boatbuilding with Keith Atkinson, where he inhaled lofting and the techniques of wooden boat building. He also learned that his inclinations were more focused on design than on working with his hands.

At age eighteen, he drew his first full-fledged boat for a friend in exchange for a few cases of beer. White Rabbit was a success. It was the beginning of his design career and led to being asked to improve the speed of racing yachts, to race with them, to go offshore. He participated in the Sydney-Hobart Race. When he couldn’t get time off to sail the Auckland-Fiji Race, he quit working in the Atkinson boat yard. Other racing events followed, and his motto to saying “YES” to opportunity became his leitmotiv.

He moved to San Francisco after being invited to commission an off-shore racer, became part of the sailing scene, met such radical boat designers as Bill Lee, and worked on various racing boats. His job at Gary Mull’s design shop raised him to his next level of competence. He raced Spirit to Tahiti and shared watches with the later well-known designer Doug Peterson.

His first successful design and build was spurred by the introduction of yachts classified as quarter tonners under the International Offshore Rule (IOR). Quarter tonners had an IOR rated length of 18 feet, 24 feet overall. Ron called her Eygthene, a take-off on the Kiwi pronunciation of 18. She won the Tampa Bay mid-winter series, where the peripatetic Ron had moved to work with Charley Morgan Yachts. He left to campaign his yacht in the US’s only entry in the Cowes Week race. His yacht won and his face graced the cover of Yachting magazine. He signed a production contract for the Kiwi 24, as the quarter tonner came to be called. Then an Irish firm offered him a job designing a one tonner. He and his wife Laurel accepted. Still only 25, he spent the next 40 years in County Cork.

His one tonner, Golden Apple, won the British One Ton Race. Ever more yachts emerged from his boards, and recognition followed in such publications as the New York Times and Sports Illustrated. He got to know the rich and famous, designed former UK prime minister Edward Heath’s Morning Cloud IV, and had lunch with him at the Savoy. His designs dominated the 1977 Admiral’s Cup. Mr. Takeda, a Japanese sailing enthusiast, led him to design yachts for the Japanese market. He bought a plane to make travel easier.

Sir Edward Heath’s Morning Cloud IV racing flat-out with Heath (top right) alongside helmsman Larry Marks and crew boss Owen Parker, 1979. Photo by Guy Gurney

One of the most compelling tales in Ron’s book is his description of the infamous 1979 Fastnet Race. Hurricane winds, monstrous waves, and a broken rudder on the 43-foot Golden Apple of the Sun left the yacht bucking aimlessly toward the Isles of Scilly’s vicious rocks. He and entire his crew were lucky to be plucked by helicopter from a half-submerged liferaft. Others were not so lucky: this Fastnet cost fifteen sailors their lives.

This calamitous event steered Ron into a new design direction: from ocean racers to big private cruising yachts. His first big maxiyacht, the 81-foot Kialoa III, was followed by a 65-foot trimaran. Monaco’s Prince Rainier ordered the design of family yacht. Commissions for yachts 100 feet or more flowed in, necessitating the manufacturing of such parts as winches and cleats, which were unavailable off-the-shelf.

Bruce Katz’s yacht Juliet, a design collaboration between Ron Holland and Dutch designers PB Design and the Royal Huisman Shipyard, launched in 1993. Photo by Guy Gurney

But dark clouds started to gather. The golden days waned after the 1987 financial turndown. Commissions dwindled; Ron sold his plane. Finally, in 1995 he was forced to declare bankruptcy (that bookkeeping he so hated in school may have contributed). He does re-establish himself over the next couple of years, although details of how he accomplished that feat are sketchy. Things pick up after he designs Mirabella V, at 247 feet the largest sailing craft ever built. Other commissions follow. Then, despite his love for sailboats, he goes to what sailors call the “dark side,” by designing large power yachts as well.

Yacht racers, yacht designers, and many who love the wind in their sails will enjoy this memoir. Ron spends the majority of his recollections on his earlier, heady years on the way to success.

One thing that’s missing in this chronicle is a lack of information beyond the designing and racing of boats. He remarks on friendships but offers few details on how they influenced his life. He marries Laurel and mentions her warmly a few times; he divorces her and marries Joanna Keltner in two sentences. Both are supportive of his design efforts, he writes.

That’s all we get to know about these two women who must tended to all household and family obligations while he followed his overweening passion and travelled constantly. Later, we’re introduced to his relationship with Canadian Catherine Walsh, who takes him to Vancouver in a sentence. He writes, however, that later in life, he explores his own psyche, goes on retreats and learns to meditate, a skill he uses when he has a serious stroke while residing in Vancouver. But about Ron’s personal life, especially as an adult, we learn little.

Today, although maintaining an office, he’s closed down his design shop rather than selling it for fear his designs will lead to cheap knock-offs. Ron consults on various yachts, teaches, lectures, and goes sailing sometimes. He enjoys looking over Vancouver’s Coal Harbour.

In the book title Ron says he learned yacht design “by the seat of my pants.” This phrase, coined when early aircraft flew without navigational aids, describes the pilots’ use all of their senses to feel lateral and vertical forces transmitted through the plane’s seat helping them to control the flight. So his book’s title is apt: Ron used all his senses, and his brain, to design boats able to win races. His lack of formal qualifications mirror the lack of aircraft instruments. But perhaps having skipped disciplined study may have provided a motivation beyond his obsession with yacht design. In the middle of his long tome, while describing his growing victories, he recalls what his teachers once said about him, “Holland will never amount to anything.” Was his quest for success meant to prove them wrong?

Ron started learning about sailing, the wind and the ocean from that first capsize at age seven. He read every nautical book he could get his hands on. He devoured yachting magazines. As a kid, he hung around boat building shops. He visited foreign boats and asked endless questions. When the near-legendary Eric and Susan Hitchcock showed up in Auckland Harbour, he borrowed a dinghy, rowed out to Wanderer III, and talked with the intrepid circumnavigators for an hour. That takes chutzpah. Later, he took apprenticeships, worked in boat yards and design shops. Sailed, raced and skippered yachts. It’s this single-minded focus, and the willingness to learn everywhere from everyone and every event that led to his success.

*

Marianne Scott is an award-winning Victoria-based writer who has specialized in marine topics since she and her husband, David, sailed from Victoria to French Polynesia in a 35-foot sailboat. For six months, they cruised the Baltic Sea in Beyond the Stars, their Hanse 411. They again explored Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands by sailboat the following year. Their 30,000 nautical miles under a keel includes other voyages in the Atlantic, Washington State, British Columbia, and Alaska. Marianne writes for many marine and other publications in Canada, the U.S., and Australia. She has authored Naturally Salty — Coastal Characters of the Pacific Northwest, published by Touchwood Editions in 2003. She also wrote a commissioned coffee-table book for the Tawainese luxury yacht builder entitled, Ocean Alexander — The First 25 Years (2006). She recently co-authored Vancouver boat-builder Ben Vermeulen’s memoir, Before I Forget (2015). She volunteers for the Maritime Museum of British Columbia, in Victoria.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply