#517 Sunlight on the Rain People

March 27th, 2019

Ocean Falls: After the Whistle. Recollections and Reflections of Life in a Coastal Company Town

by R. Brian McDaniel

Victoria: Printorium Print Works, 2018

$40.00 / 9781999420703

Reviewed by Howard Stewart

*

The story of a town that no longer exists is destined to be poignant, at least in places. The fact that it’s a story about a coastal pulp and paper community turned ghost town makes it doubly sensitive. Here in British Columbia, we’re used to the ephemeral nature of our mining towns: booming today then naught but ruins and memories tomorrow. The disappearance of a town built to transform our super abundant coastal forests into paper is more daunting. Didn’t we devise our vaunted “sustained yield” forestry system to prevent that kind of thing?

The story of a town that no longer exists is destined to be poignant, at least in places. The fact that it’s a story about a coastal pulp and paper community turned ghost town makes it doubly sensitive. Here in British Columbia, we’re used to the ephemeral nature of our mining towns: booming today then naught but ruins and memories tomorrow. The disappearance of a town built to transform our super abundant coastal forests into paper is more daunting. Didn’t we devise our vaunted “sustained yield” forestry system to prevent that kind of thing?

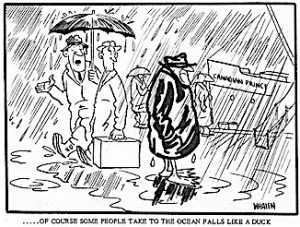

I mean, if Ocean Falls was vulnerable, then what about Campbell River? Powell River? Crofton? The most obvious answer is that the fate of Ocean Falls was also sealed by far more rain than they get in those other places, at least a hundred inches more each year. Indeed, the residents called themselves the Rain People. Also, by its crushing isolation. Ocean Falls was always unreachable by the sacred automobile and during its final decades, even the coastal freighters were less frequent and less comfortable. So, while those places around the Strait of Georgia are able to slowly transform themselves giant retirement homes, Ocean Falls couldn’t. If the flow of old people to the south coast starts to dry up though, other communities may want to look for lessons in the Ocean Falls experience.

Ocean Falls, circa 1970. The pulp mill town was situated at the head of Cousins Inlet, off Dean Channel

Underlying causes of Ocean Falls’ collapse and death are not the subject of this book however. Instead McDaniel has carefully crafted a detailed celebration of that place. We get the whole Ocean Falls story, from its founding early in the century to its so-called “normalization” (the odd name given to the town’s destruction) in 1985. But the central focus of the book is the heyday of Ocean Falls, from the mid-1940s to the mid-1960s when the author was growing up there.

This book is certain to be interesting for people with ties to Ocean Falls, and towns like it. And, as the author reminds us, those with ties to Ocean Falls are legion. An estimated 70,000 people passed through the place between 1906 and 1980, and 50,000 of them actually worked there. Not bad for a town that, at its peak in the early 1960s, had only about 3,000 inhabitants; its work force topped out at 1,400.

This vast flow of people through Ocean Falls over the years would theoretically be enough to entirely re-populate the town every three years or so. Again, it comes back to its intense isolation, half way up the coast between Vancouver and Prince Rupert, and weather that was frequently less than optimum. The average annual rainfall was about 150 inches and some years there was more.

McDaniel remembers Ocean Falls though, as a fine and nurturing place to grow up. During most of its existence, he says, the company was a benign influence. One of the many things the American owners did well, apart from managing their business effectively and paying their workers very well, was working hard to encourage their employees to stay for a while. Well, the right people of course. Labour organisers were tolerated but “eccentrics” did not do well. The unemployed were on the next boat out.

There were a great many European immigrant workers but very few First Nations people in town; mill work apparently didn’t suit them. The town’s population was one-third Japanese-Canadian at the start of the Second World War but, as happened all over the coast, every one of them was deported east of the coast after Pearl Harbor.

It’s fortunate that the company was benevolent, because they controlled virtually everything, with the notable exception of a tiny suburb that emerged latterly. Provincially and federally, the town voted more solidly NDP than most places — seldom an asset in BC’s venal politics — but there was no municipal politics to speak of: the company governed its town.

McDaniel recognises that, among the armies of single men who poured through the soggy grey town, some could harbour memories different from his own. Most workers — including present premier John Horgan — passing through stayed in Ocean Falls just long enough to get up a grubstake: enough for a mortgage, a car for the future, or whatever, but not a moment longer:

Of all the locations of paper mills on the coast of B.C., Ocean Falls was probably the least desirable. There were no roads in or out. The noisy and foul-smelling mill was separated from the town by a 200-foot river clogged with debris and effluent. It was surrounded by mountains that blocked the sun and captured the rain…

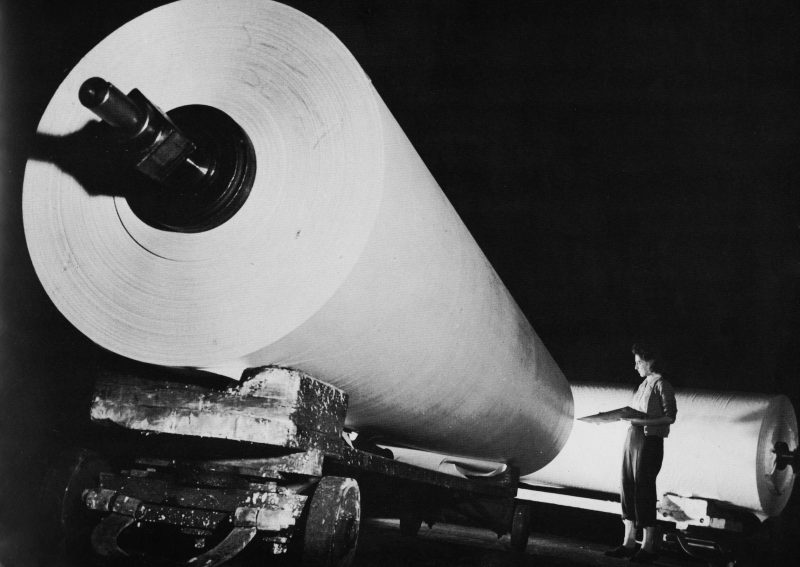

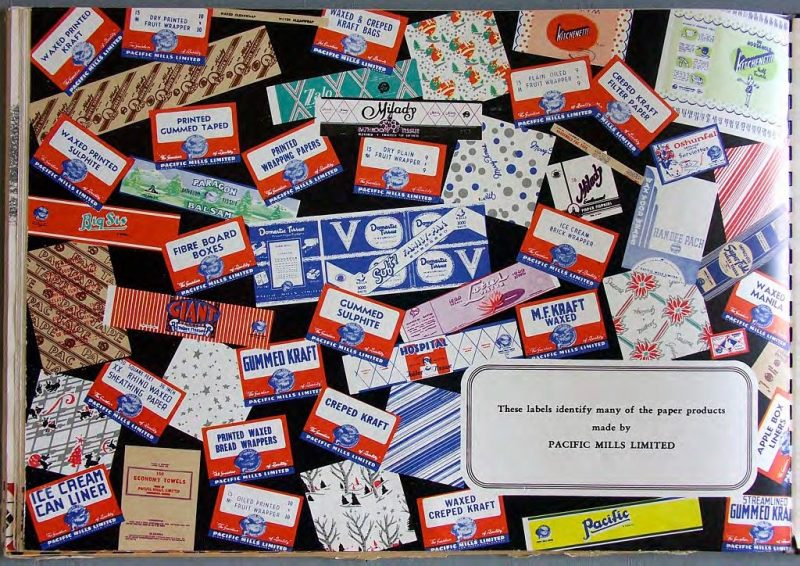

Inspecting finished rolls of newsprint, female wartime replacement worker, circa 1944. Pacific Mills photo

Yet those who accepted the company’s welcome, put down roots in Ocean Falls, and made it home, found it had a lot to offer. Well, maybe not a lot, but what it did offer was interesting and welcoming for people who went there to raise a family: good paying and secure jobs (until the bottom fell out in the 1970s) in a safe and friendly town where the spectacular nature of the B.C. coast started at their doorsteps. And opportunities to excel at sports.

Like many from my demographic, I expect, I remember Ocean Falls as a town that was hard to find on the map, even before it was deliberately destroyed. Yet somehow, it kept sending us spectacular swimmers. One of these swimmers himself, McDaniel explains that the town was very conducive to fitness in general, and organised sports like swimming in particular. The town had no cars and many stairs, the company provided first class sports facilities, and the coaching was excellent. Things like television and cars that might distract kids in other places came much later to Ocean Falls, or not at all. One result was that this tiny town in the middle of nowhere sent athletes, mostly swimmers, to every Olympic Games from 1948 until 1972.

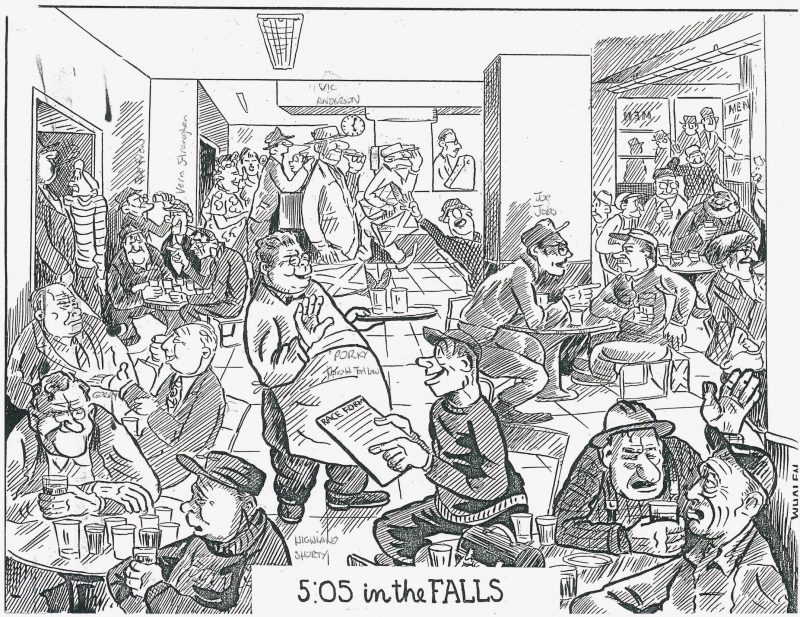

In many ways Ocean Falls was two towns: there was the one where McDaniel grew up inside a happy family supported by a benevolent company. There was also the dark, stinky, and foreboding one where many thousands of workers came ashore for a while to earn some serious money. For many of the latter, it was a place that offered little to do besides work and little to spend your money on except beer and poker, especially after they closed the facility at Pecker Point. McDaniel has done a fine job of presenting the perspectives of both kinds of people.

In the process, Ocean Falls, its characters, and the paper factory that caused it all, are brought to life in detail so rich it’s almost archaeological.

*

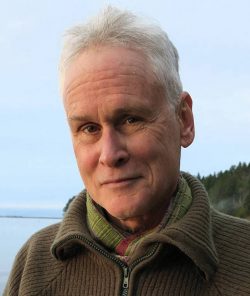

Howard Macdonald Stewart is author of Views of the Salish Sea: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Change around the Strait of Georgia (Harbour Publishing, 2017). A geographer and semi-retired international consultant whose work has taken him to more than seventy countries since the 1970s, Howard has reviewed books for The Ormsby Review and BC Studies. His 17,000- word story of a 1973 bicycle trip down the Danube with the Canadian war hero and debonair cyclist Corny Burke (Lt.-Cdr. Cornelius Burke, DSC) was published by The Ormsby Review #21 (September 28, 2016), and he is working on an insider’s view of four decades on the road entitled Bumbling through the World on Someone Else’s Dime. Volume 1, Discovering the Americas will be out soon. He has lived on Denman Island, off and on, for more than thirty years.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

I worked at OF for a total of three years as a young man in the 1950’s.

Wonderful, wonderful memories of people and place.

Brian McDaniel’s book is a great read – for me, a treasure.

Bill Day