#451 Fathers & sons on the Salish Sea

December 19th, 2018

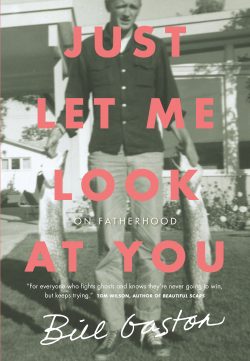

Just Let Me Look at You: On Fatherhood

by Bill Gaston

Toronto: Penguin Random House (Hamish Hamilton), 2018

$19.95 / 9780735234062

Reviewed by Howard Stewart

*

The sub-title of Bill Gaston’s new book declares it is “on fatherhood.” The publisher had to narrow it down, I suppose, to keep it pithy. Because, as the cover photo suggests, it’s also about fishing. And about death and the ravages of alcohol. Not incidentally it’s also about boating in the north Salish Sea, especially at the mouth of the Skookumchuck Rapids, the most terrifying corner of this otherwise benign inland water. Not unlike the grim reaper, this tidal torrent is better seen from a safe distance, as it pours in and out of the mouth of Sechelt Inlet like clockwork, relentless and eternally threatening to sweep away the unwary or careless.

The sub-title of Bill Gaston’s new book declares it is “on fatherhood.” The publisher had to narrow it down, I suppose, to keep it pithy. Because, as the cover photo suggests, it’s also about fishing. And about death and the ravages of alcohol. Not incidentally it’s also about boating in the north Salish Sea, especially at the mouth of the Skookumchuck Rapids, the most terrifying corner of this otherwise benign inland water. Not unlike the grim reaper, this tidal torrent is better seen from a safe distance, as it pours in and out of the mouth of Sechelt Inlet like clockwork, relentless and eternally threatening to sweep away the unwary or careless.

The big difference of course, is that no one escapes the dark maelstrom of death in the family or, eventually, one’s own. Gaston’s story takes us to the edge of both furies and back a few times, spanning most of his life and, eventually, most of his dad’s. We know his dad is going to die, has already died, yet Gaston keeps us engaged. He does a masterful job of sharing his feelings and stories about his father, and about losing him: first to alcohol, then to dementia, and finally to death.

As the grownup son of a loved but deeply flawed father, Gaston grapples especially with questions surrounding his father’s vain struggle with alcoholism, another kind of maelstrom, one that could have been avoided — at least theoretically — but wasn’t. By the end of the book, after contemplating his dad’s impoverished youth at Mukilteo on the shores of the south Salish Sea, the younger Gaston comes closer than ever to understanding the influences that moulded the elder Gaston.

But the book’s title, Just Let Me Look at You, might also be a subtle hint that he’ll never really get that close. On the one hand, Gaston is looking (back) at his father; like many of us, I expect, he is looking longer and harder than while the patriarch still lived. But “just let me look at you” was also one of his father’s favourite lines, a stock phrase he trotted out when meeting with the adult Bill, on occasions when the younger Gaston felt his father was looking at him but seeing little.

Am I making the book sound gloomy and dour? A good read only for those who enjoy wallowing in pathos and sustained, profound, introspection of a kind that I find often borders on self-indulgence? The kind of book that I would normally avoid like the plague?

In other hands it might have been so. But Bill Gaston has written a book that broaches these weighty and emotional subjects while taking us on memorable and funny boat rides and fishing expeditions, many of them set in and around Egmont, a quirky outpost on the banks of a Sunshine Coast fiord, aboard two generations of stink pots.

These are the settings for the greatest intimacy, the best face time between the author and his boozy executive father as they indulged a shared passion for a sport that usually demands more talk than action. In these places we’re introduced to a series of memorable characters and much fishing lore. Gaston also reminds us of the frighteningly rapid decline of the once rich salmon populations around our inland sea, and obliquely acknowledges the role sport fishers have played in this catastrophe. At one point, he even foreshadows the drama played out recently at Vancouver’s Sun Yat Sen Gardens as he recounts his own failed struggle with a wily koi-killing otter.

Anyone who is both a father and a son will, I suspect, find himself comparing Gaston’s experiences with his own, especially if his is a fishing family or one ravaged by alcohol. My own capacity to share in the spirit of the author’s musings was limited by a father who didn’t fish, didn’t drink, and died young.

And yet inevitably, like Gaston, I wonder how I’m seen by my grown sons. And this leads me, also inevitably, to reflect on my own evolving evaluation as a father, and more generally to hope that our sometimes intense assessments of our erstwhile role models might mellow with time, as it has for Gaston.

Some father-son relationships are short on both contact and affection. Gaston shares a bon mot from Oscar Wilde, who quipped in An Ideal Husband that “Fathers should be neither seen nor heard. That is the only proper basis for family life.” And for almost fifty years I’ve remembered the shock of listening to American writer Henry Miller talk of his father. Even in his dotage, Miller detested his old man and the smug suffocating bourgeois life the elder had planned for the younger Miller. Gaston grew up watching his father drink himself into an alcoholic muddle on a regular basis, then pretty much throw in the towel completely when he got older. Yet Gaston, unlike Wilde or Miller, has managed to salvage good and happy memories of the man and achieve some understanding of what made him the way he was. A glimmer of hope then, for all flawed fathers — and for the sons who seek to understand them.

*

Howard Macdonald Stewart is author of Views of the Salish Sea: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Change around the Strait of Georgia (Harbour Publishing, 2017). A geographer and semi-retired international consultant whose work has taken him to more than seventy countries since the 1970s, Howard has reviewed books for The Ormsby Review and BC Studies. His 17,000- word story of a 1973 bicycle trip down the Danube with the Canadian war hero and debonair cyclist Corny Burke (Lt.-Cdr. Cornelius Burke, DSC) was published by The Ormsby Review #21 (September 28, 2016), and he is working on an insider’s view of four decades on the road entitled Bumbling through the World on Someone Else’s Dime. Volume 1, Discovering the Americas will be out soon. He has lived on Denman Island, off and on, for more than thirty years.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply