#444 Carpenters and vagabonds

December 11th, 2018

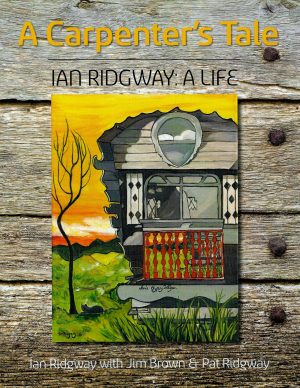

A Carpenter’s Tale: Ian Ridgway, A Life

by Ian Ridgway with Jim Brown and Pat Ridgway

Elphinstone: Gypsy Deluxe Books, 2017

$30 / 9781775008309

Orders: patridg201@gmail.com

See also: http://www.suncoastarts.com/patridgway.html

*

Mudflat Dreaming: Waterfront Battles in 1970s Vancouver and the Squatters who Fought Them

by Jean Walton

Vancouver: New Star Books, 2018

$24 / 9781554201495

*

Both books reviewed by Ron Verzuh

*

There’s something’s happening here. What it is ain’t exactly clear.

– Buffalo Springfield, “For What It’s Worth” (1966)

The generation that came of age in the late 1960s and early 1970s adopted the anti-war protest song “For What It’s Worth” as an anthem of the counterculture. It spoke to something inside us that cried out for freedom from all the restrictions inherent in the established social order. Now come two new and very different books to refresh our memories of those heady, hedonistic, and often confrontational times past.

The setting is British Columbia’s Lower Mainland and the key players are two groups of young people who found themselves in violation of society’s social norms. A Carpenter’s Tale offers an autobiographical view of what happened at a squatter community on Vancouver’s North Shore, while Mudflat Dreaming is a journalistic account of a similar community’s struggles in North Surrey.

The first takes us on a fun-filled tour of community members’ lives, referencing many of the events and activities that marked Vancouver’s counterculture scene. The second focuses on what happened when a rag-tag group of squatters was threatened with expulsion from their makeshift homes. Both are about dreams that might have been, as the two groups intersected with and challenged the values of mainstream society.

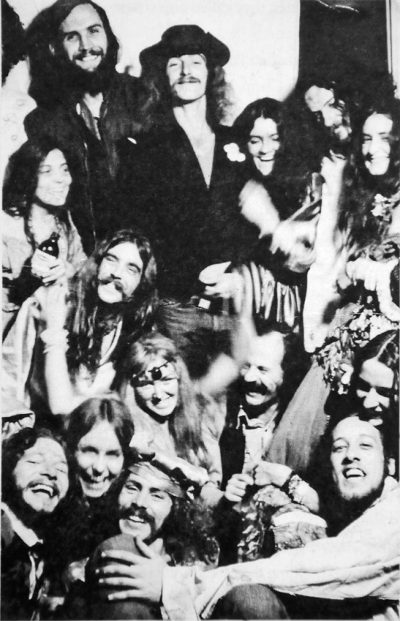

DeLuxe carpenters and friends (Ross, Mel, Irene, Willy, Marguerite, Dan, Wendy, Gerry, Joyce, Bug, Al Clapp, Kenny, and Helen) at the Stranded Canadians Overseas League (SKOL) benefit at the Commodore Ballroom, 1970

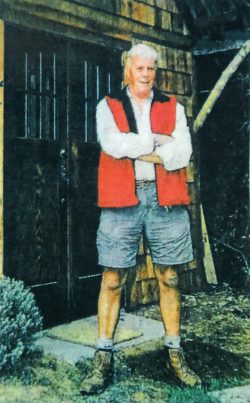

An enterprising young man from England turned hip bon vivant, Ian Ridgway knew the music scene in the United Kingdom from early skiffle bands through to blues and rock, and he names many names to prove it. Perhaps his long-time friendship with Long John Baldry was part of the reason that the rock legend moved to Vancouver for a time.

Ridgway played guitar with Baldry and other early 1960s bands, but to make a steady living he learned carpentry. He was good at it and people always needed something built, particularly stages and houses. It also gave him the independence he wanted and a welcome to the community of fellow hedonists he met in Vancouver.

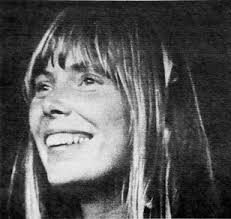

The book’s 53 short chapters recall Ridgway’s many involvements as a carpenter-musician, providing behind-the-scenes background to seminal counterculture events like the Strawberry Mountain Fair, a rock and arts festival held in 1970 outside Vancouver, the Langley Pleasure Faire, the Mission Pleasure Faire, where folk great Joni Mitchell made a surprise appearance in 1971, and various other Ridgway adventures.

There’s a full chapter on the “book in a bag” about the Mission Pleasure Faire. Like many other Ridgway-inspired projects, it was a collective enterprise. People contributed photos, drawings, and poems that were printed on separate sheets of offcut stock from publisher Talonbooks. Others worked on the batik cotton bags that would then be stuffed with the pages. Soon “our little book in a bag was out on the streets,” co-author Jim Brown recalls. “Pages were already being tacked up on people’s kitchen notice boards or bathroom walls” (p. 125).

The collective ethos was especially apparent when Ian and his extended family moved to the North Shore mudflats, where a group of artists, free spirits, and homeless vagabonds had set up what was viewed as a hippie community. Ian was in his element, building homes for his friends using driftwood and other materials that could be scrounged from abandoned buildings.

“Making people’s dreams real and making it fun” (p. 228) is a theme running through Ridgway’s account of his life and times, and that’s exactly what Ridgway’s Deluxe Building Collective did. They created their own jobs and made subsistence-level incomes by selling art, crafts, and music. They were musicians, like Ridgway, poets, save-the-whale activists, feminists, crafts artists, and actors. They were also social outcasts.

This was Ridgway’s playground and it was replete with images of long hair and macramé skirts gyrating with abandon to the music that would set you free. You can almost hear the sounds of the Mamas and Papas, Creedence Clearwater Revival, and the Grateful Dead reverberate thunderously through the pages of this collective biography. And you can almost feel the floor shaking at the Commodore Ballroom as the crowd stomps to Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen.

The playground included the music of local folkies like Joe Mock and the Mock Duck and Shari Ulrich, their songs echoing from the bistros and coffee houses of Kitsilano’s Fourth Avenue. Canadian music greats like Joni Mitchell, Perth Country Conspiracy, and Fireweed also slip onto the pages of this homemade book of surprises and delights.

It was a magical playground that in Ridgway’s early days in Vancouver featured the Retinal Circus on Davie Street, a prominent hip venue with fabulous psychedelic light shows and bands like Country Joe and the Fish, the Youngbloods, and the Velvet Underground. At the Alcatraz Hotel you could buy a dime bag or a gram of hash with your order of a round of 20-cent draft beer for the table. At the Cecil Hotel, Ridgway and friends might share the company of luminaries from the San Francisco and Black Mountain poetry scene mixed with the local TISH poets and other intellectuals.

Ridgway’s voyage down memory lane includes much of this, and his account will resonate with many Baby Boom members of the counterculture. It might even serve as a slightly uncomfortable reminder to some of the high school years when they were weekend hippies riding past the blue-smoke of Vancouver’s hip scene in their fathers’ cars, hoping for a peek at the freak show from another planet.

Certainly Ridgway’s account will cast some back to a time when they were envious of the freedom they saw, or conversely were happy to have missed the bad vibes and bad trips. But the Ridgway book — part memoir and part the shared accounts of friends, family, and associates — mostly celebrates the excitement and fun. Indeed, the large-format book presents a carefree romp through those times and yet mixed in it are memories of the politics of the period.

For example, there are chapters describing the launch of Greenpeace, the Gastown Riot, and the battle to save the North Shore mudflats from the developer’s wrecking ball. Several chapters are devoted to the Pleasure Faires described as “interactive theatre events where the enchanting gingerbread gates and towers of a craftsman’s village became a magical setting for strolling minstrels, jugglers, and happy children” (p. 10).

One chapter recounts the making of the great Robert Altman movie McCabe & Mrs Miller in 1970. Ridgway and other mudflats dwellers were hired to build the sets and Altman found them suitable to play the role of extras. As Ridgway recalls, though, some of the crew got booted off the set after imbibing too much “white lightning.”

Still another chapter reminds us that famous British-born novelist Malcolm Lowry (Under the Volcano, October Ferry to Gabriola) once lived in Dollarton near the North Shore mudflats. Noting that Lowry was “Ian’s famous fellow-countryman,” the chapter suggests that he “found a similar source of energy and rebirth while living among the squatters” (p. 226).

Ridgway’s “tale” is a personal account of what was happening here. But it is as much an extended family album (there are many illustrations) as it is a biography. Two of those family members, Jim Brown and Ian’s wife Pat Ridgway, applied their writing and editing talents to help consolidate this lifetime of shared hip adventures.

With so few Baby Boomers having penned their memoirs of the 1960s — Myrna Kostash’s Long Way From Home: The Story of the Sixties Generation in Canada (Lorimer, 1980) is still among the best — the Ridgways and Brown have pulled a welcome trigger for our own memories of those wild times.

*

Mudflat Dreaming is a sympathetic account of what happened to the squatter communities. Author Jean Walton spent part of her youth in Surrey and had some connection to the flats people there and the struggle for their community’s survival. She was thus able to rely on personal memory as well as local news reports to flesh out what happened.

Jean Walton at Maplewood mudflats with Ken Lum’s “From Shangri-la to Shangri-la,” an installation consisting of squatters’ shacks, one third of their original size. Photo by Marlene Mussell

In doing so, Walton does a good job of recalling the political side of the fight to keep the mudflats from being destroyed. Her portrayal of former B.C. premier Bill Vander Zalm, then the Surrey mayor, exposes him as the fool he often was. Other business stakeholders are also exposed. And this is the strength of the book.

Walton now teaches film studies at Rhode Island University and much of her commentary is based on her analysis of three films that were made about the flats. Focusing on the films, while a way of visualizing the mudflats scene, was not as effective at recreating the alternative atmosphere that we encounter in the Ridgway biography. Often I felt I was examining what happened through the filmmaker’s lens rather than the author’s own perspective.

Her interviews with squatters tend to shortchange the reader by using more paraphrase than verbatim comments. The quotes drawn from the interview with popular Vancouver actor Jackie Crossland, for example, are as much about Walton’s exploration of herself as about Crossland.

Walton also relies too much on novelist Malcolm Lowry’s short story, “The Forest Path to the Spring,” to situate the story of the mudflats. Did his time spent near Dollarton a decade earlier really have anything to do with what happened after he left?

The publisher’s blurb on the Walton book says it “traverses the intersecting domains of activist and documentary film, waterfront environmentalism, urban land use, utopian experiments, and working class struggle.” A tall order for any book, and to her credit she accomplishes some of those goals. But she fails to engage us in the same way that Ridgway and friends do through their personal stories.

*

The politics of the counterculture also comes into play in another recent book about mud. Mudgirls Manifesto: Handbuilt Homes, Handcrafted Lives (New Society Publishers, 2017) tells the story of a group of women calling themselves the Mudgirls Natural Building Collective. This is happening decades after the mudflats of North Vancouver and Surrey, but the connections are interesting (Mudgirls Manifesto is reviewed by Kate Braid in The Ormsby Review #343, August 14, 2018 — Ed.)

More ideological than the utopian mud communities described by Ridgway and Walton, the women see a clear connection between their efforts and fighting rampant capitalism. The mudflats dwellers also felt they were challenging power structures, but they did not apply a left-wing ideological worldview to it. They just wanted to be left alone to have a good time and they objected to the local authorities stepping in to ruin it.

Ridgway and Walton help us recall a time when innovative alternative lifestyles were calling out to the world to change while change was still possible. In a time of climate change denial, perhaps the Mudgirls collective defines the difference between something happening here and there, then and now.

*

Ron Verzuh is a writer, historian, and documentary filmmaker. His book Underground Times — Canada’s Flower-Child Revolutionaries (Toronto: Deneau, 1989) is a history of Canada’s 1960s underground press.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply