#414 Good art and bad habits

November 05th, 2018

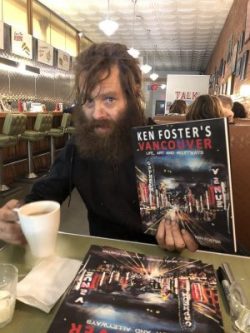

Ken Foster’s Vancouver: Life, Art and Alleyways

by Sean Nosek and Ken Foster

Vancouver: Granville Island Publishing, 2018

$49.95 / 9781926991917

Reviewed by Robert Amos

*

I like this book. I like the energetic paintings, I like the way the writer presents the artist’s unique life story, and I admire the artist’s determination to create. Wouldn’t want to be him, but I appreciate this chance to visit the world of Ken Foster.

I like this book. I like the energetic paintings, I like the way the writer presents the artist’s unique life story, and I admire the artist’s determination to create. Wouldn’t want to be him, but I appreciate this chance to visit the world of Ken Foster.

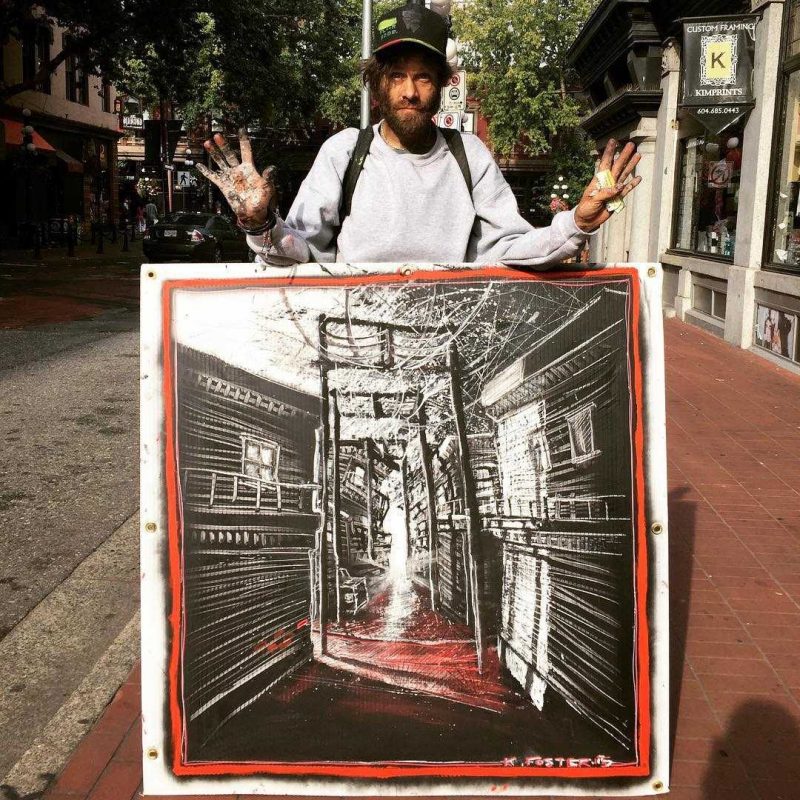

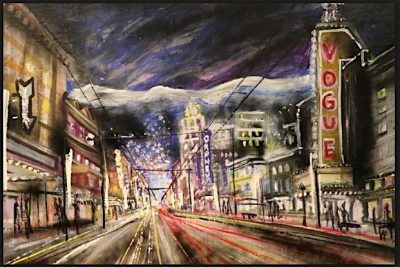

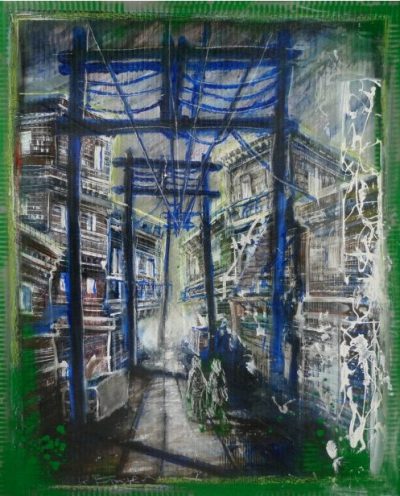

Ken Foster’s Vancouver is a place I recognize. He paints the railway tracks along the waterfront, Gastown and Coal Harbour and False Creek. He paints Granville Street and the wired-up back alleys within those downtown blocks. Foster paints it all at night, with neon and rain-slick streets under bruised skies. He takes a perverse pride in painting on “found objects” with ready materials like spray paint, and he blasts his images into place in a hurry, without a backward glance. Like all the best art, they are very much of his time and place.

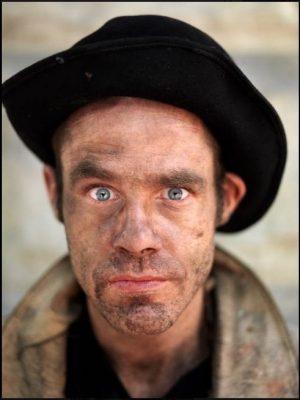

Foster has made downtown Vancouver his place, like Canaletto painted Venice and as Ken Done has done with Sydney. But Foster has done it without any royal patronage or the backing of a fortune made from giftware and the tourist trade. Sean Nosek tracked him down in an SRO – single room occupancy hotel – in the DTES – Vancouver’s Downtown East Side. Make no mistake: Foster is a long-term drug addict who has paid for his habit over the years by selling his paintings on the street.

“Up a dilapidated flight of stairs,” Nosek begins, “I check in at reception and leave my identification at the desk.” Foster’s room is impossible to get into — so packed with stuff it’s been declared off limits by the fire marshal. He sleeps in the “safe use area,” an injection site behind the reception desk.

Maybe that’s not the best place to interview the artist. Nosek found him more at home in the back alley, “a place of refuge,” Nosek calls it, “a place far removed from the eyes of society, where one can squat in the corner, shaking and shivering and desperate, and not be judged.” Foster often paints the fire escapes and overhead wires there, and the void at the end of the street. It’s “a portal to a dark and secret universe,” Nosek suggests. “Is this not a manifestation of the emptiness, the hole, that every addict longs to fill?”

In his sympathetic text, Nosek writes about the path that led Foster to this place. Born in 1970, the artist was adopted by a family in Ottawa, who brought him to Delta in 1978. During his teen years, skate culture drew him in: “it had the right degree of danger and was suitably badass and antiauthoritarian.” He and his gang carved their way across the urban landscape of the financial district, high on weed and acid and cough syrup and alcohol. Tagging, graffiti, street art, and murals were part of the scene. Crack and heroin followed later.

Foster tried to channel his talent, with two years at Kwantlen College, a year at Emily Carr College of Art and Design, and a session at the Vancouver Institute of Art. But the two great themes of his life — art and addiction — wouldn’t allow him the time to fit into anybody else’s system. To get the money his habit requires — $200 every day — he has to create constantly.

“Why do you think I work so hard to sell paintings?” Foster asks. “Sometimes I barely sleep.” Nosek makes a surprising comparison. “His level of devotion would rival that of an Olympian or a concert pianist.”

There have been high points. In 1992 he became a parent to his daughter Cypress. In 1997 the producer of a Rolling Stones video, Bridges to Babylon, flew him to Los Angeles to paint a graffiti mural for them. But Foster’s also been to jail a couple of times too. “There is something admirable,” Nosek muses, “about how he has stayed true to his path.”

It’s normal to view drug addicts as useless and reprehensible but meeting Foster in the pages of this book might cause you to reconsider. He’s a high-functioning painter who’s been attracting paying customers for decades. That can’t be easy.

Couldn’t he just stop using drugs?

“Why would I want to do that?” he replies. “My drugs are how I frame my day. How I space my time. It’s how I reward myself. There’s nothing wrong with it, other than how society looks at it. The only problem with it is they’re just so expensive.”

The writing about the artist and his addictions is interesting, but this book isn’t about the words. It’s about the pictures, lots of big coloured pictures showing Foster’s grand and gritty vision of the city. It’s a true picture of the city by someone who knows it all too well.

Maybe this book will change Ken Foster’s life. It’s easy to imagine a stable future for him, followed by an even bigger book, and then a big show at a prestigious gallery, followed by jaw-dropping prices for Foster paintings at auction houses. Perhaps we’ll look back on the pictures in this first album as those rare, early works painted back when he was pure and unspoiled.

For now, this is a valuable record of our time and place, and I am glad it was published.

If Ken Foster speaks to you, then you should know about another book. It came out seventeen years back, but treads some of the same sidewalks and deserves to be better known. Artist Keith McKellar (a. k. a. Laughing Hand) wrote and illustrated a profound and extensive meditation on the history and texture life of the streets and cafes of downtown Vancouver. It’s called Neon Eulogy (Ekstasis Editions, Victoria, 2001) and it’s packed with a unique blend of detailed local history, hep cat poetry and obsessive pen drawings. I can unreservedly recommend it — it’s on my bookshelf right next to Ken Foster’s Vancouver.

*

Robert Amos has become known as “the man who paints Victoria,” and his paintings have entered the permanent collections of the City of Victoria, the University of Victoria, and the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. Amos was the art writer for the Victoria Times Colonist newspaper for 32 years and during that time interviewed many of Victoria’s finest artists. Nine books of his paintings and writings about Victoria have been published by Orca Books and TouchWood Editions. In 2010 his book, Inside Chinatown, (TouchWood, with Kileasa Wong) received the Award for Outstanding Achievement from Heritage B.C., and most recently he released the best-selling E.J. Hughes Paints Vancouver Island (TouchWood Editions, 2018). Amos was made an Honorary Citizen of the City of Victoria (1985) and was elected to membership in the Royal Canadian Academy of the Arts (1996).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply