Brain Surgery at Zero Rock

While circumnavigating Vancouver Island in a sailboat, Brian Harvey reflects on his past and a malpractice lawsuit against his dead father, a neurosurgeon.

March 18th, 2019

Winter Harbour, where Brian Harvey encountered less than rosy sports fishermen.

Harvey’s account evokes icy winds, malevolent rocks and environmental eyesores. He also writes of weird parallels between boating and brain surgery.

Sea Trial: Sailing After My Father

by Brian Harvey

Toronto: ECW Press, 2019

$21.95 / 9781770414778

Reviewed by Theo Dombrowski

*

Brian Harvey’s Sea Trial defies easy description. In fact, that is exactly one of its – considerable — strengths. The outline is simple enough: the author records a two-month sailing circumnavigation of Vancouver Island, while, concurrently, going through a box of legal documents related to a malpractice lawsuit against his dead father, a neurosurgeon.

Brian Harvey’s Sea Trial defies easy description. In fact, that is exactly one of its – considerable — strengths. The outline is simple enough: the author records a two-month sailing circumnavigation of Vancouver Island, while, concurrently, going through a box of legal documents related to a malpractice lawsuit against his dead father, a neurosurgeon.

That’s where the minor miracle of good writing takes over from the facts. With works of non-fiction it is tempting to speculate what kind of book would have resulted from exactly the same information in the hands of a different writer. In Sea Trial just about every word bears the imprint of its author — we say “author,” but it is probably safer to say “persona,” for who knows — or cares — what the “real” Brian Harvey is like (to the extent that any of us has a “real” version of ourselves).

Given the unmistakeable personal stamp in this book, we can be grateful that our guide is so engaging. Here is a voice that cares — and cares deeply. Yet only towards the intense conclusion do the emotions become torrential. For the most part, the voice is generally breezy, bright, even when it is intensely engaged: through thick and thin (and there is plenty of both) there is something almost “British” about the writing. Self-deprecating humour, lightness of touch, and an inclination to give a wry account of his own (substantial) fears and uncertainties make his a very easy voice to listen to, whether chatting about rocks and reefs or lawyers and legalities. His accounts of learning to sail and of taking courses in seamanship, for example, are hilarious: “One gloomy video was a re-enactment of the death of an entire family from CO2 inhalation: the actors rolled their eyes and went down like tenpins” (p. 142).

Further, with a sharp eye for telling detail, and inventive language, Harvey is a writer who knows how to fix on the less to evoke the more — and, simultaneously, to give a sense of the inner life of stuff. Consider his description of sports fishermen (not his favourite group of sea faring folk). “Early the next morning…the docks were coming alive with coffee-clutching sport fishermen heading out for the first bite, stamping their feet and coughing while the outboard motors rattled in the clouds of vapour” (p. 248).

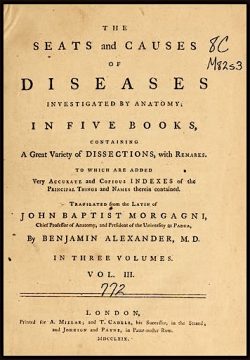

More than a vividly sensory recorder, though, Harvey has a mind and imagination that penetrates. Reading through the history of the branch of medicine relevant to his father, he finds his mind drifting:

I found it hard not to think about the past — and not just the flash and sizzle of my father’s life and career, no more than a mosquito caught in the bug zapper on a hot summer night, but the drawn-out, deeper drone of ghosts long past.

I found myself conjuring the scene in Morgagni’s time: the anatomists bent over the small body on the table….

Even in the present, he looks at a stack of legal papers and mulls, “Some poor soul had spent hours over a photocopying machine, dizzy with ozone, hand-feeding flimsy pink carbons.”

Some readers might engage in a little eyebrow raising when it comes to one of the manifestations of this heightened imagination. Those allergic to “magic realism” (and there are many of us) might disengage during the ghost scenes. Yes, ghost scenes. The ghost of the elder Harvey makes several appearances, usually when Harvey is alone at night in the cockpit. Still, these visitations are easy to take. Short and lightweight, they primarily allow a fanciful interchange between father and son, a chance to probe memories, to expose values, — and to toss off the odd bit of humour.

Another trait leads in a completely different direction. Harvey is a social animal. He likes meeting people. In anchorage after anchorage he sidles up to others for a chat. His capacity to describe, evoke, mimic, and mock (usually, but not always, affectionately) leads to one of the book’s most entertaining features. “How do you deal with irrational people?” he asks at one point, “Especially when you’re tied up next to one at an abandoned dock? Listen to their concerns? Call the cops?”

… The man stuck out his hand. There was a lot of dirt under his fingernails. Brent had a huge head, tangled grey hair, and yellowish horse teeth that I would see a lot over the next few hours. His high forehead was creased in parallel chevrons, as though he was constantly struggling with some weighty conundrum. We shook hands while I read his T-shirt: GARDEN NAKED …. He looked slept-in.

The memorable character portraits are not limited to these social encounters, though. By far the funniest — and most endearing — are the rest of the crew, Charley and Hatsumi. Charley, you must understand, is a schnauzer. Charley cannot swim. Charley’s bladder, his opinions on rough seas, other dogs, squirting clams, rich sports fishermen and much else, are drily recorded.

Hatsumi is quite another case. Hatsumi is Harvey’s wife. Although one could wish she figured more prominently — or, at least, more explicitly — her presence permeates every moment of the trip. Like Charley, Hatsumi, too, has opinions. She also has skills — considerable skills. In fact, without her navigational abilities (her commands yelled up from the cabin of an imperilled Vera) it seems unlikely that Harvey would have lived to tell the tale. Prominent amongst her many characteristics is her Japanese background. Spotting a Japanese flag on a nearby boat, Harvey, ever the extrovert, proposes a visit. Not so Hatsumi: “But we don’t know them!” she avers. Not for the first — or last — time Harvey reminds us, carefully, “Sometimes, my wife could be quite Japanese.”

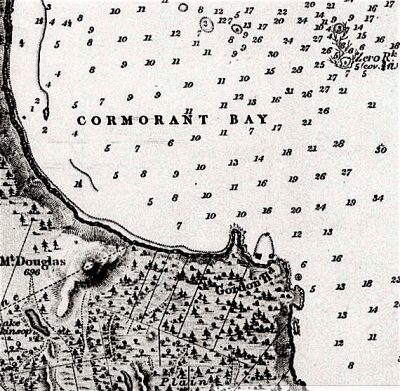

Zero Rock in Haro Strait, Cormorant (now Cordova) Bay, from Captain Richards’ survey, HMS Plumper, 1858-60

In fact, the book is arguably less about either a sailing trip or a legal case, than it is about Harvey himself. So infused is he in everything he observes, remembers, or discovers (in his father’s papers), that, the overwhelming impression we are left with is of a man at sea.

Similar qualities emerge not just in the writer’s voice, but also in its narrative methods. From the first page, we are clearly in the hands of a writer determined to shape his materials. Consider the opening pages. Before we have time to gain our sea legs, we are in the middle of a crisis. Ploughing off course, almost blinded by dark and fog over Nahwitti Bar, Vera plunges into giant, weirdly undulating waves. And before the ordeal is over, Harvey takes us into the midst of another, equally terrifying, boating crisis, this one many years before, by Zero Rock, with an eight-year-old Harvey cowering away from certain death.

And thus the book proceeds. Never predictable, it repeatedly veers off course. The author knows his storytelling techniques. Repeated motifs (like the Zero Rock incident), foreshadowing aplenty, flashbacks (especially to the early experiences with Vera), and side channels into history, make the book richly discursive. A few examples should illustrate.

Consider the way that Harvey concludes his account of the hearty cheer of sports fisherman: “Things weren’t always so rosy with them though, as we would learn firsthand in Winter Harbour a week later.” The tension, thus established, tightens its grip on the next section of narrative. In a different way, the Zero Rock memory threads together almost the whole book. In a particularly gloomy anchorage, for example, he falls into “unsatisfying sleep,” and “dreamed I was ten years old again, trapped in the middle of Haro Strait. This time, though, I was sitting on Zero Rock with the seals, watching my father struggle past” (p. 200).

Still, the book can be read as a straight-ahead travel book, a vivid — but intensely personal — account of a sailing trip around a large, dangerous island. Very, very few readers are likely to put down Sea Trial and rush off to the nearest yacht broker to buy a sailboat. On the contrary. Rhapsodies on the glories of scudding along azure billowing mains under a resplendent sun are, at best, few and far between — not altogether absent, but very few and very far between. And, the postcardy bits are overshadowed by Harvey’s vivid evocations of icy temperatures, dripping, impenetrable fogs, savage winds, treacherous currents, malevolent rocks, and towering seas. And, to add to the general impression, the trip is a greasy litany of mechanical crises — leaking oil, broken starters, failing batteries and more, enough to lead to a whole chapter being called “The Second Law of Thermodynamics” — the tendency, that is, of not just the entire universe to drift toward disorder, but, also, Vera.

Some writers would use these crises as an opportunity to suggest (or even underline) their prowess and fortitude. Not Harvey. There is no swagger here. Dread, panic, nerves, anxieties — and self-criticism — inflect every gust and lurch. When, early in the book, he groans about his nervous bladder and the overwhelming urge to pee, we suspect we are not going to be spending much time with a coolly swaggering male ego.

Of course, the emphasis on the dangers of the trip makes for gripping reading, not least of all because, except for the very last few bits of the voyage, the dangers come in so many different forms — and never cease. One of the more blissful passages is illuminating: “…we surfed an undulating sea of mercury that, when the sun was out, threw back a dazzling reflection of towering white clouds and blue sky. The horizon, at those moments became a wavering silver ribbon.”

If the passage had stopped there, all would be well. It doesn’t. Harvey can’t resist adding, “…the motion was lulling and seductive — or would have been had we not entered the stretch of coastline where there were exposed rock pinnacles as much as five miles out sea. The chart looked as though a waiter had leaned over my shoulder and murmured, ‘Some ground pepper with that?’” The evocation of the sailing is beautiful and the concluding bit is, typical of Harvey, playful and inventive, but the undercurrent of anxiety never, ever, leaves.

As for the natural beauties independent of sailing, of course there are some of those. Pointy mountains and emerald forests pop up on cue. Also on cue, are guest appearances of puffins, wolves, dolphins, sea otters, and whales. These, however, get comparatively short shrift.

Quite a different kind of shrift is given to dereliction and decay. In every harbour or nook, Harvey comes across rust, rot, and abandonment. Passing quickly over whales and otters, he lingers over details of wreckage. Of one an old tug he writes, “The hull paint was long gone and the iron cladding was curling off the wormy-looking wood in rusty leaves, like scales on a dried-out fish.” Not content with this level of detail, he makes sure we learn of the cockeyed and corroded steering station, with a “rusty wheel,” a broken ladder, and a “rusted-out metal chair that looked as though it came out of a high school auditorium.” The descriptions aren’t, however, just pictorial. Harvey’s coast breathes history, an elegaic history of a coast dotted with disappointed hopes and failed lives.

Beautiful British Columbia. Clearcut logging of an old-growth forest, west coast of Vancouver Island. Garth Lenz photo

On the dark side of the ledger of observations, too, lurk the environmental sores. The first references to clear-cut mountainsides and fish farms are a little toneless. As the trip progresses, though, the logging becomes “profoundly depressing,” and the fish farming even more disturbing. In fact, the fish farms present a particular problem, because, as we learn, the author is, in his professional life, tasked with writing a scientific account of their environmental impact. Daunted by the single-minded vehemence of “both sides” of the “sordid fight” (p. 309), however, Harvey reaches a critical turning point. He will not, upon returning, write his report: “Nobody’s going to win this battle, or if they do, it won’t have anything to do with science.” And why the despair over the power of truth? Clearly (but not quite explicitly), his discovery of the distortions of truth in his father’s malpractice suit make him ask himself, “how would my words be bent and re-formed to suit other peoples’ agendas?”

And here we approach the daunting kernel of the book: the malpractice suit. At first, Harvey prepares us for a quiet meditation on his father’s personality: “ I wasn’t interested in judgment — of him or his accusers — and I decided right then that if I looked any further into this story it wouldn’t be with any romantic idea of exoneration” (p. 34). In fact, he seems to turn almost hopefully to this opportunity truly to know his father.

Even during the earliest, most cursory phase of looking at the papers, though, things change. Words like “rancid,” “sordid,” and “lurid” in regard to the lawyers and newspapers are not incidental. And, as it turns out, with good reason.

Harvey takes pains to make a seamless link between discovering the coast and understanding the documents. Part of his justification for the simultaneous ventures is that both the box of notes and the interest in sailing (“love of sailing” isn’t quite right) are “gifts” from his father. At times there may be a whiff of trying too hard, especially as he pushes the analogies between the court case (involving hydrocephalism) and sailing.

While explaining the complex workings of fluid pressure in and around the brain, for example, Harvey writes, “a tiny failure somewhere in the chain can crash the whole system, as surely as a single submerged rock can hole a ship and sink it.” When he speaks, later, of “the weird parallels between boating and brain surgery” (p. 232), he perhaps reveals more about his joint preoccupations than about either boating or biology.

At times, though, the connections are powerful: reviewing transcripts of an interrogating lawyer, he writes, “Reading them in this lonely anchorage, where night and fog had now fallen upon Vera like a shroud, made me wonder, How alone had he felt, closeted in that room with two lawyers and a stenographer?” Even more to the point, however, Harvey feels ever-mounting reluctance to look at the papers, ever-mounting disquiet and pain, even as his own “sea trials” become increasingly harrowing. It is tempting to wonder whether this parallel crescendo is quite true to the facts. In probably the most important sense there is a lot of truth here. And reading about it is increasingly compulsive and taxing.

Arguably, Harvey does four things to make this part of the book so disturbing. First, he meticulously documents the incompetence and deviousness of the opponents in the case. Second, he creates a portrait of his father who, though gristly, is an intensely likeable and admirable man, sailing into court with naïve faith in the “truth.” Third, he makes wrenchingly clear how much and how long his father suffered from the results of the lawsuit. Fourth, and probably most important, he admits the distress he himself goes through in battling his way through the documents. Remove any one of these elements, and the book would lose a lot of its punch. Put them together, and you have the recipe for a harrowing read.

First, then, consider those who initiate the unhappy events. Careful about not saying anything direct about the patient’s parents, Harvey nevertheless seems unable to resist irony: “Billy’s family was officially upset in 1976…. The evidence of just how upset they were arrived at my father’s house in an envelope, dated December 5, 1984, an early Christmas present.” Again, saying nothing very much and trying to be “impartial,” Harvey stands back and quotes Billy’s mother directly as she speaks of the elder Harvey: “If anything went wrong with (Billy), he could help me get a so-called normal child and said he would be a vegetable…. ” Clearly he wants the reader to see. No flinching allowed. When, however, it comes to reacting to the mother’s claims that Billy had, before the medical crisis, been “precocious,” Harvey’s restraint breaks down completely. Of a poem that Billy wrote, Harvey writes hilariously, but savagely, it “was unlikely to have been penned by a carrot.”

But the parents become almost beside the point as the documents get more and more grotesque. The real villains of the piece — and, yes, by the end they do seem villains — are, first, the newspapers, second, the judge who seems incapable of understanding the gaudy mistruths, and third, the “lawyers [who] were paying other doctors to have expert opinions.” The notion of the “expert” for hire takes a huge pummelling. In detail after numbing detail, Harvey drags the reader through a painful sequence of contradictions, ignorant assertions, and even lies.

At the same, time, though, the other real purpose of the investigation, to discover the elder Harvey’s character, is movingly achieved. At the beginning, Harvey claims that “Trying to connect the dots between the handsome violin-playing medical resident and the querulous old man with the haunted eyes and the fly away hair didn’t enter my mind.” If forcing himself (and it does take a lot of forcing in the end) to go through the documents does achieve anything truly significant, it does that. It connects the dots. “Mysteries” that had surrounded his father’s life decisions are, in the end resolved. Perhaps the most overriding of those — why his father never got over the malpractice incident, even though it was settled out of court, turns out to be precisely because it was settled out of court. As a result, the aging doctor, principled to a fault, feisty, yet grimly humourous, never had the opportunity to defend himself publicly.

In solving this mystery, the son really exposes his own vulnerabilities and compulsions. Though he doesn’t quite say so, Harvey and/or the book’s persona, in writing the book, seems to be doing what his father never had been able to do — go public. In this, the reader has a crucial role to play: it is hard not to escape the sense that it matters, it matters a lot, that each of us reading the book is part of an ultimate tribunal.

The mariner up the mast in a storm. Engraving by Gustave Doré

The public function of the book, though, is mirrored by a private one. By the end of both “journeys,” Harvey is wrung out. In admitting to “forcing [his] way through” the “excruciating reading,” he admits to a “month of fear and frustration.” Always the one to eschew melodrama, he mutters dismissively about his “little meltdown” at one point, and at another, deflates the theatrical gesture of flinging down a wodge of papers by having Hatsumi call up from the cabin, “I’m trying to do yoga down here.”

Appropriately, the book concludes, “we did the usual things with winches and jib sheets, the sails filled again, and we headed home.” Some might hear echoes of probably the most seminal sea voyage in Western literature, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner:”

He went like one that been stunned,

And is of sense forlorn:

A sadder and a wiser man,

He rose the morrow morn.

*

Born on Vancouver Island, Theo Dombrowski grew up in Port Alberni and studied at the University of Victoria and later in Nova Scotia and London, England. With a doctorate in English literature, he returned to teach at Royal Roads, the University of Victoria, and finally at Lester Pearson College at Metchosin. He also studied painting and drawing at the Banff School of Fine Arts and at UVic. Theo is the author and illustrator of popular guide, travel, and hiking books including Secret Beaches of the Salish Sea (Heritage House, 2012), Seaside Walks of Vancouver Island (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016), and Family Walks and Hikes of Vancouver Island — Volume 1: Victoria to Nanaimo, and Volume 2: Nanaimo North to Strathcona Park (Rocky Mountain Books, 2018). Theo Dombrowski lives at Nanoose Bay.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply