#342 The woodsman & the economist

August 14th, 2018

My West Coast Surveying Adventure

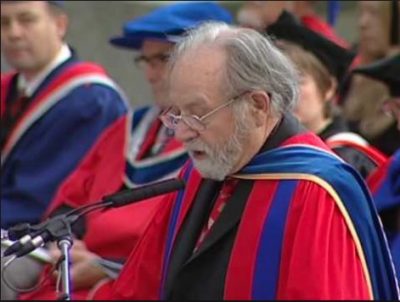

by Richard G. Lipsey, OC, FRSC

*

We are delighted to present a memoir by Richard (Dick) Lipsey, arguably one of Canada’s foremost economists—and it’s not about economics. Here Lipsey recalls his work as a surveyor’s assistant and axeman on the west coast of Vancouver Island in the summer of 1947.

By his own admission, Lipsey was an “indifferent” student when he had just finished his first year at Victoria College. Here, he describes how a summer spent working in the mountains changed and challenged him in positive ways. He had just turned nineteen.

“I got an enormous personal charge in knowing that I had gone, in one long and eventful summer, from a frightened, inexperienced, out-of-condition guy,” he writes, “to an experienced and reasonably competent woodsman.”

That fall, in September 1947, Lipsey went back to Victoria College for second year studies and enrolled “in three courses that were to change my life: the History of Western Philosophy, Introductory Psychology, and Introductory Economics.

“During that year, I transferred my main intellectual stimulus from outside to inside the classroom. Economics especially was a revelation. I found I could do it intuitively. I always seemed to know one step ahead of the lecturer just what assumption was needed to complete the argument.” [1]

After two years at Victoria College, Lipsey transferred to UBC, where he received a first class honours BA in economics in 1951, followed by an MA from the University of Toronto and a Ph.D. from the London School of Economics in 1956. Lipsey held professorial posts at the London School of Economics, Essex University, and Queen’s University, and ended his distinguished career as a professor of economics at Simon Fraser University (1989-1997).

Now 91, Richard Lipsey has retired in North Vancouver where he is still writing. — Ed.

[1] See Richard G. Lipsey, “Introduction: An Intellectual Autobiography,” in Macroeconomic Theory and Policy: The Selected Essays of Richard G. Lipsey, Volume Two, (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 1997), pp. i-xxii.

*

In 1947, I was part of legendary Vancouver Island surveyor, Alfred G. Slocomb’s herculean efforts, along with others, to complete the 1946-1948 topographical survey of the west coast of the Island. The prodigious efforts of Slocomb and his colleagues [i.e., us!] resulted in the first editions of the maps that we use today.[2] My role was a small one; but it had a large influence on my life and character.

I was born in Victoria in 1928, was educated at Cloverdale elementary school until the middle of Grade 4, then Willows elementary school, Oak Bay High School, and Victoria College, which was then a part of the University of British Columbia, whose main campus was located in Vancouver.

During my first year at Victoria College, a friend of my mother’s knew one of the B.C. land surveyors who was looking to add to his crew for the summer’s topographical survey of a section of the west coast of Vancouver Island around Nootka Sound. This sounded like a good idea to my friend, Alan Barnes, and myself, so we met with the surveyor, Alf Slocomb, at his office in (or near) the parliament buildings.[3] During the interview, he asked us how we were with axes. Alan replied truthfully that as his family had a stove and furnace that burned wood coal, he was competent with an axe. I lied and said that I was also competent with an axe, although, given that we had an oil furnace and an electric cooker (not too common at the time), I had never had much to do with axes. Despite, or maybe because of my small lie, we were taken on.[4]

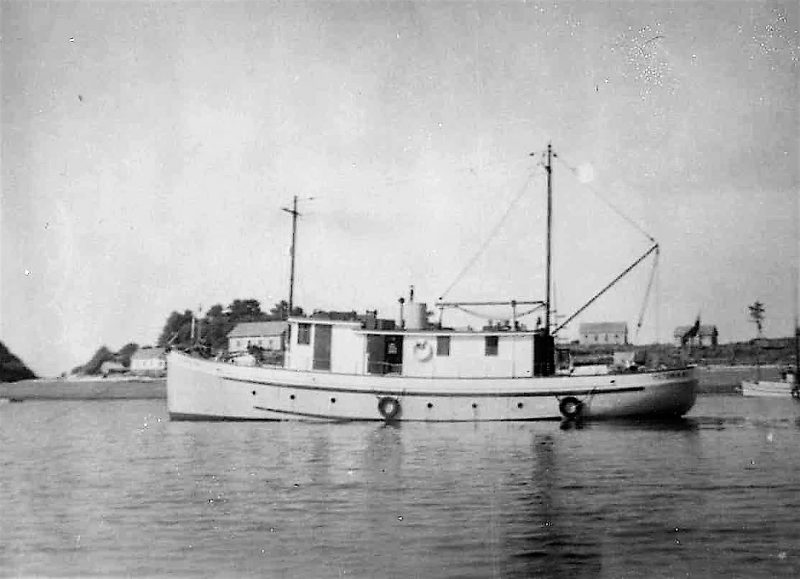

As soon as the college term finished, sometime in May 1947, we went to the dock at fisherman’s wharf near downtown Victoria to meet the rest of the crew. Our ship, the B.C. Surveyor, was about 55 feet long, diesel-powered, and had just been purchased by the B.C. Department of Lands and Forests from its previous owner.

The design was a forecastle that slept six in twin bunks, one set on each side of the cabin and one set on the aft bulkhead. Then a large engine room behind the forecastle, a wheelhouse directly above the engine room where the captain, Fred, slept, and a saloon behind the wheelhouse where we all met for meals and other group activities. For the rest, I have no clear recollection. There must have been a galley where Harry, our ancient cook, prepared our meals and slept. (Incidentally, Harry claimed that in his earlier days he had once sailed with Jack London!).[5] Finally, although I never saw that part of the boat, there must have been two cabins in the stern. One would have been for the assistant surveyor, Art, who we liked a lot, and other for Slocomb, who was known as the Chief and, at least to our young minds, was a rather stern and aloof figure.

Top row: (L-R) Alfred Slocomb, Burt the cook, Fred the captain. Middle row: Dick, Doc, Geoff. Bottom row: Spencer, Alan, Rod.

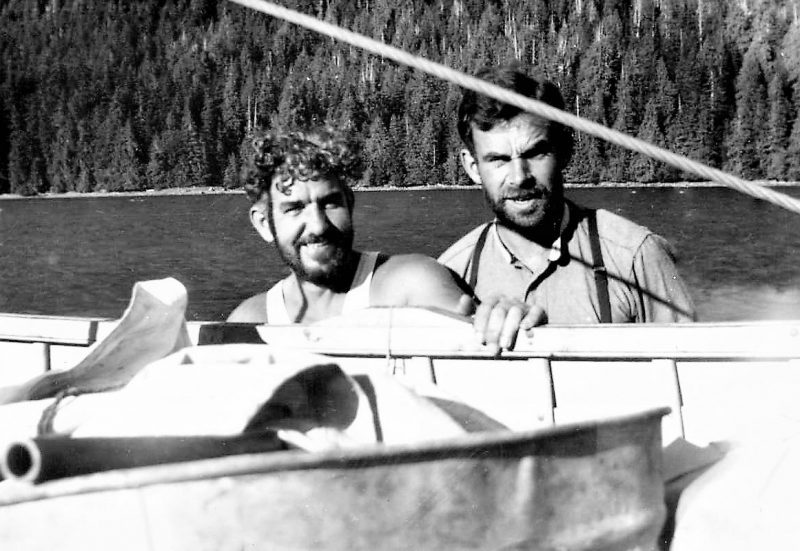

Six of us slept in the forecastle. Rod, an apprentice surveyor, was closer to the bosses than to the rest of us. Then came we five axemen. The student contingent was myself, Alan Barnes, and Spencer Davies, the son of good friends of my parents who had joined the crew unbeknown to us and who was handy with radios, and Jim Johnson — I think that was his real name, but to us he was “Doc” as he was a pre-med student at UBC — a low key person who had been with Slocomb the previous year.

The group was completed by Geoff, who was somewhat older than the rest of us and had a rifle with which he proposed to shoot game. He was designated the engine room chief while I, having had some boating experience, was designated his assistant. The captain gave signals from the bridge by a rudimentary engine room telegraph system. We altered the engine according to these signals, which were neutral, slow ahead, half ahead, full ahead, slow astern and full astern.

Once, the five-foot gear lever jammed while we were coming at some speed into a wharf. When the captain signalled for full astern, Geoff could not move the lever. With great presence of mind, he ran to the end of the engine room, turned and at full running speed hit the lever. Fortunately, it gave way and he managed full astern just in time. Needless to say, the captain was livid until Geoff explained that he was not sleeping at the switch, just coping with an unexpected problem.

The boat needed a lot of work and we lived at home and worked on it all day for some weeks before it was ready to sail. Eventually, we set off sometime in early June, rounded Race Rocks, and headed up the West Coast of Vancouver Island. At that moment I decided to grow a moustache, increasingly apparent in the pictures that follow. It remained until we again passed Race Rocks on our return journey in September.

In the previous year the Chief and his group had surveyed a piece of land just south of our destination at Nootka, but had lived in tents with only a powered dingy to take them to the places where they were to head inland. So, on the way up, we had to stop where he had been last year to show off his new boat. During one of these trips to a small settlement, we went aground on a sand bar, fortunately on a rising tide. A problem arose when someone dropped our only oilcan overboard. We could see it on the bottom, through the crystal clear water with the tide rushing by it. I was the only one who volunteered to retrieve it. Someone pushed a pike pole to the bottom near the can to guide me. I dove in and grasped the can just before the rushing tide could take me away.

Shortly thereafter we stopped for some “R & R” at a hot springs, where we had a lovely bath in the rocks from which the hot mineral water sprang. Although I did not know its name at the time, it was almost certainly the hot springs at what is today the Maquinna Marine Provincial Park.[6]

The heavy Pacific swell was about normal for that time of the year and, coming at us more or less on our port quarter, it created a rather uneasy motion. As a result, Doc was severely seasick the whole trip. Alan and I, who did not get seasick, kept a watch on him, helping him whenever we could. We also kept assuring him that once we got to our destination, the roles would be reversed with him guiding and reassuring us, as he did many times during the early days of our land-side adventures.

Finally, we arrived at our destination, a cove on the south east of Nootka Island, with a jetty, fish cannery, and workers’ bunkhouses on stilts along the shore stretching from the jetty. That settlement is no longer on any current map, so it must have been abandoned. Not far to the south on the island was a First Nations settlement at Friendly Cove, which is still there.

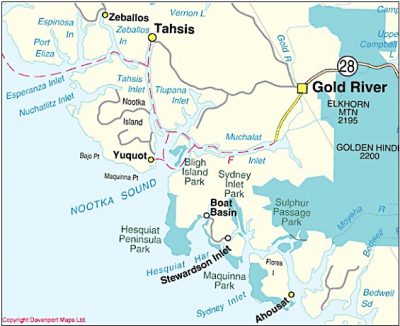

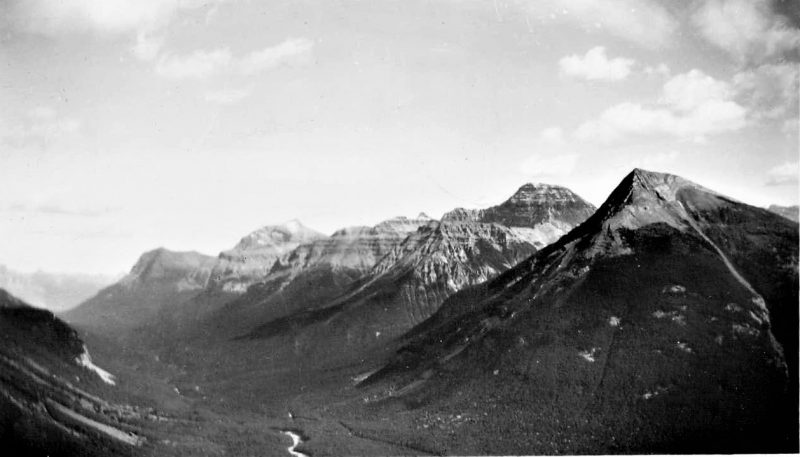

At the time I never saw even an outline map of the area that we were to survey, but it ran roughly from the end of Muchalat Inlet up the centre of Vancouver Island, including the Gold River and Gold Lake, then west to include Conuma Peak, and I think Malaspina Mountain, then south just west of Tlupana Inlet all the way to Nootka island. There were at the time no settlements in our whole area, except at the cannery site and Friendly Cove. There was no road to the head of Muchalat Inlet, as there is today, and no other settlement north of us before the small towns of Zeballos and Ceepeecee that were just outside of our area.

At the time I never saw even an outline map of the area that we were to survey, but it ran roughly from the end of Muchalat Inlet up the centre of Vancouver Island, including the Gold River and Gold Lake, then west to include Conuma Peak, and I think Malaspina Mountain, then south just west of Tlupana Inlet all the way to Nootka island. There were at the time no settlements in our whole area, except at the cannery site and Friendly Cove. There was no road to the head of Muchalat Inlet, as there is today, and no other settlement north of us before the small towns of Zeballos and Ceepeecee that were just outside of our area.

The scenery was spectacular, with deep fjords, mountains often rising straight out of the water’s edge, and snow patches in the more sheltered crevasses.

On paper our job was simple: to climb the key mountains in the area carrying the equipment that the surveyors used for triangulation. The peaks we climbed ranged in height from three to five thousand feet, and a few were slightly higher. We carried on our backs our tents, sleeping bags, food, the surveying equipment and, of course, our axes. As far as I remember the surveying equipment was a tripod, a transit, and a large, heavy camera.

The boat was to take us up the various fjords to the closest point to our mountaintop destination where we would come ashore and begin our journey. The typical land trip was four or five days. The first day was usually through the rain forest where windfalls of enormous first-growth trees meant that we were sometimes walking on rotten logs six to eight feet above the forest floor. Unfortunate was anyone who fell into the morass below. Enormous devil’s club ferns were all around, the overall effect being something almost Jurassic Park-prehistoric. We used the trails made by wildlife whenever we could, but otherwise we had to go straight through the undergrowth. It was so thick that we were often forced to cut our way through it with machetes.

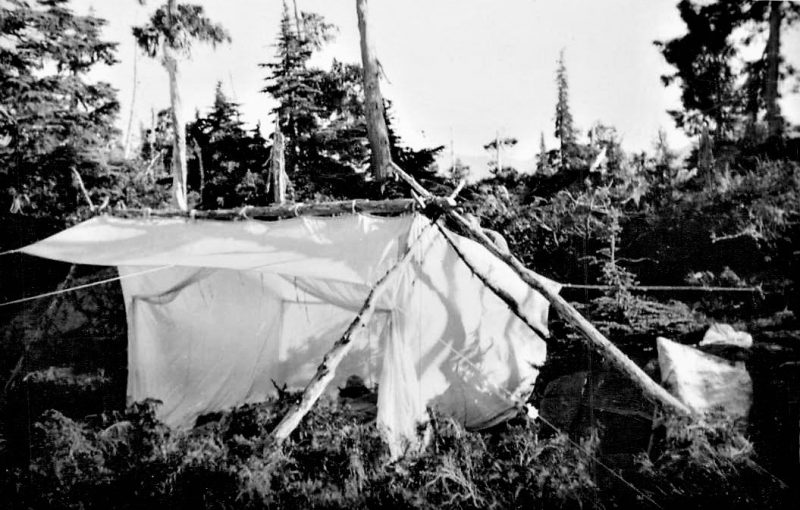

At the end of this day we would set up our base camp, usually part way up the mountain free of the worst of the undergrowth. Once we had found a suitable flat spot, some of us would cut down slender trees and strip them to make poles for our tent. Others would gather firewood: twigs to start the fire and larger pieces to burn; we were lucky if we found a fallen yellow cedar as its wood came off in conveniently sized shakes and was highly flammable. After cooking and eating a meal, we would enter the tent and collapse into our sleeping bags.

On the second day we would climb to our selected peak. There was usually plenty of rock-work, some of it on pretty steep faces. We accomplished this without any climbing equipment and in tough hobnailed boots better suited for bush than rock. Once we reached the top of our current mountain we had, if it was wooded, to cut all the trees and shrubs that would prevent all around 360° sightings. The surveyor would then read angles of elevation and direction to each of the other selected points in the area while one of us recorded these in a journal.

Back in the office in the winter, the surveyors would take the sights of horizontal and vertical angles from each point to all of the others and use them to calculate the contours of a topographical map. When the readings were completed, we used hammer and chisel to make a hole in in the rock and then cement in a metal medallion giving the year of the survey.

We would then build a cairn on top of the medallion, using rocks if we were above the tree line or poles if we were below it. These would be used for the surveyors to sight on when we climbed other mountains later on. Usually the cairns were on mountain tops but sometimes we set them up on the points of islands where they would be visible from all sides.

Once the mountaintop work was done, we would head back to base camp. If we left it too late, it would be dark before we got back to our camp and one would not dare to travel in this rough country after dark. Fortunately, we never got trapped after dark away from our camp, but several times we came close to being too late.

One of us was almost always left on the ship to act as engineer in case it had to be moved. This was usually Geoff, but occasionally me.

The rest of us were split into two groups. The Chief led one, often with three axemen. The other two axemen, which usually included me when I was not left on the boat, were in the group headed by Art. I regarded being in his group as a stroke of luck because I found Art a sympathetic character while Slocomb was, to my mind at least, a rather frightening figure.

As soon as our boat was moored at Nootka, we assembled on the jetty and the Chief read angles to various distant points while we practiced recording these in a journal as he called them out. It turned out that I was very bad at this, as I was at most things that we had to do. Spencer Davies seemed much better, so he was given the job over me. Later in the winter, Art told me that some of the recordings made by various members of the crews were faulty, causing them a lot of trouble when drawing their maps. Although at one time or another, several of the axemen acted as a recorder, it was never me — so happily my general ineptitude could not be blamed for at least this one trouble.

We were also each presented with a long handled axe and a file. The others quickly set to using the file on their axe. Greenhorn that I was, I had no idea what they were doing and was afraid to show my ignorance by asking. By some indirect means I finally figured out that they were sharpening the blades of their axes. I set to on mine but did not do a very good job being almost totally ignorant of axes.

While we were on the jetty looking straight up Tlupana Inlet, we saw a high needle-like peak that looked to us to be about 5,000 feet in elevation, which we soon learned was called Conuma peak. We joked about the impossibility of climbing such a mountain. As we were laughing about it, the Chief told us that was the first mountain we had to climb. Being the most commanding peak in our area, it was necessary to get a cairn on it right away and get readings from it to other key points. Then at the end of our time here, we would climb it again and read the angles to all the other cairns we had erected in the meantime. With a sinking feeling in the pits of our stomachs, we retired to our bunks. (A web search tells me that Conuma Peak is called the Nootka Matterhorn, is 4,837 feet in elevation and that “Alfred G. Slocomb twice visited the summit in 1947…”)[7]

For the first month or six weeks, the weather was frightful with rain most of the days. A recourse to google tells me that the current annual rainfall in the sound is 130 inches and in the mountains behind the sound I am sure it is even more. But after only a day or two in the dock the sunshine returned. The Chief announced that tomorrow morning his group, which included my pal Alan, was off to climb Conuma Peak while Art’s crew would take on a nearby mountain that although still looking formidable, seemed not quite as daunting as Conuma.

To my disappointment, Geoff was asked to go with Art’s crew while I was to stay on board as engineer in case the boat needed to be moved.

We anchored at the head of Tlupana inlet and the two groups set out, leaving me to stay with the captain and cook and not much to do but swap tales with the captain. Our cook, Harry, stayed by himself pretty much all of the time. He was a “waste-not” man and if we did not eat something at one meal, it would reappear at the next meal. This included uneaten fried eggs from breakfast, which would reappear for lunch, cold and greasy. The captain and I got that treatment a day or two into our stay together. Unwilling to face eating the cold fried eggs at lunch, we crept on deck and tossed them overboard. Minutes later, having triumphantly returned to the wheelhouse, we were dismayed to see them floating beside the ship. We tried to retrieve them with the pike pole but they just slowly floated away. Fortunately for us, Harry was resting in his bunk after lunch and the eggs passed away on the tide before he saw them. We fantasied that had he seen them, they would have reappeared on our plates for the next meal, all dripping in brine.

After four or five days, the two parties returned to the boat and Alan told me the climb was one of the most frightening things he had ever done: scaling near-vertical rock faces with pack boards holding heavy surveying instruments and no rock climbing equipment of any sort. Don’t forget most of us were completely untrained in mountaineering and had none of the special equipment that a modern climber would think essential.

We returned to Nootka for a well-earned rest. Then the rain came again. It fell and fell day after day After the nerve-wracking climbs that the two crews had just endured, all were glad to be able to sit around doing little or nothing. On one day when the weather was not quite so bad, several of us were sent out to find a lake that was shown on our aerial photographs — we had these for our whole area — as being near the middle of the Island. I do not recall what readings we were supposed to make there although it does not matter for this narrative as we never found the lake. On our way back from pushing through the dense bush, we did come across a derelict boat on the shore, well south of our jetty.

Finally, there was another slight let-up in the weather and Art announced that we could sit around no longer and would head off to our next destination. This time Geoff stayed on board and I went with Art’s crew to climb a Peak called Kleeptee, linked by a sharp ridge to a second slightly lower peak. We set off and I can still remember getting ready on the beach for my first major climbing adventure, tying our boots then having a last minute rest. We reckoned that the typical backpack weighed about 50 pounds and when it was necessary the long axe was tied onto one side of the pack and extending below it.

Travelling was never easy with all of this equipment, especially if rock climbing was needed to reach what was to be our base camp. In addition, since Spence said they had run low on food last time he allocated to each of us much more than was needed. So, we had to remove the canvas containers from the back packs and substitute large bags which had to be tied onto the pack board — not a good idea when every pound of extra weight was a burden as we fought our way through the rain forest or climbed steep rock faces. Since I was unversed at knots, mine did not hold steady for long, making travel even more difficult than it would otherwise have been as the bag sagged lower on my pack board.

We set off into the rainforest and by afternoon the rain had returned. By the time we made camp, we were drenched along with everything we carried. Wet and cold we climbed into our damp sleeping bags. The next day on our final ascent from base camp to mountaintop, we only needed to carry the surveying equipment. We did a lot of rock climbing in the rain and when we reached the top we could see almost nothing. So, we built our cairn and then went back down to base camp. We reached the boat the next day and when the clouds cleared momentarily, we saw that we had climbed to the wrong, slightly lower, peak. We named it Kleep and were told we would climb the right one, now called Tee, later in the summer.

Except for Geoff, none of us axemen had ever been away from home for any length of time — a home where mother did all the chores. So, we were shocked when the Chief called us into the saloon after several weeks out and said that the forecastle was a disgrace; it was dirty and the heads filthy — a disease trap. We were surprised: did these things not just do themselves? Faced with the reality that there was no mother or fairy to do these things, we decided to have a rota for cleaning the heads and the forecastle. I volunteered to be the first to do the cleaning job, which would be by far the worst one as the toilet had not been “serviced” for over a month, nor the floor cleaned over the same time period. I worked for about half a day until it all gleamed. I fell back then with a real sense of accomplishment, one of the first that I had had since arriving in Nootka.

About a month into our stay Harry, our cook, became ill and had to return to Victoria. Later in the summer we heard he had died soon after arriving in the city. His replacement, Burt, soon arrived — much younger, much more fun and a more imaginative cook. He was also an old hand with the cards.

On days off, which we called Sundays no matter what was the actual day of the week, we began to play poker at Burt’s instigation. I had learned poker hands in a game called Royal Rummy at a much younger age but had never played serious poker. At one session, I had a pat hand in five-card stud: a king showing and a king in the hole. Since no aces and no pairs were showing in the other hands, I had a sure winner. I checked the betting and when it came around to me again, I raised the ante quite a bit. When the hands were shown and I had won, Burt blew his top: “You do not check a pat hand,” he shouted at me in anger. Never again was I so silly as to do anything except make a serious bet on a pat hand — all part of growing up, which we axemen did a lot of in this, our first serious time away from home.

We had many dramatic experiences while en route to our mountaintops. One which sticks out vividly in my memory occurred while I was climbing a rock face, as usual with heavy hobnailed boots and no safety equipment. It was before we made our base camp and so I was burdened with a heavy pack. The end of my long axe handle caught in a rock crevasse and every time I moved, the top of the pack with me attached to it, pivoted an inch further out from the rock face. If that had gone on much longer, I would have tumbled backwards the couple of hundred feet to the level ground below. Fortunately, my calls of distress were responded to by a member of our crew who came from below me and freed my axe handle so that I could continue up the rock face, clinging on for dear life.

On another occasion, we were crossing a stream carrying serious weight on our backs. The water level being quite swollen with runoff, came to somewhere near our knees so that it was difficult to hold our footing. If you have not tried to wade a swollen stream, you have no idea of how strong the water can be. Alan Barnes (I think it was him) was several steps ahead of me when he stumbled. He was left standing but bent at the waist with his head in the water with his fifty-pound pack going over his head to pin him down with his bum sticking up. I rushed forward and pulled on his pack, freeing him to straighten up. He took a big breath, and thanked me for saving him.

Yet another time we were climbing a not-too-steep rock wall when Alan, who was a bit separated for us, came across a narrow ledge, which he followed. Rounding a corner, he came face to face with a cougar who was going the other way on the ledge. According to Allen they looked at each other for a few seconds and then the cougar decided that Alan was the real menace and so slipped off the ledge, down the rock, never to be seen again. Yet another narrow escape from possible serious harm.

During the first six rainy weeks we became used to setting up camp with damp or soaked equipment. Geoff, who had no desire to tramp through the forest, usually stayed on board the boat in case it became necessary to move it, while I went ashore with one crew or another, usually Art’s. My axe work only improved slowly and I was usually the laggard of our group as we cut through the rain forest undergrowth or climbed the early stages on the ascent to the mountaintop. I had not played sports in high school and started smoking at sixteen so that, although I had worked on a farm for two summers during my high school years, I was not in good shape for serious exertion.

My reputation as being a general problem was not helped when my new boots disintegrated (heavy hob nailed bush boots that were not up to the beating offered by the West Coast jungle) and I had to send back to Victoria for a replacement. I developed such an inferiority complex about my axeman abilities that I failed to recognise even the few good things that I had done, including braving the strong tide to retrieve our oil can, cleaning up the sordid mess in the forecastle that no one else wanted to face up to, and helping my friend Alan when he was trapped in the water.

When I was with Art on our first ascent to any mountain, all three of us went to the top so that there were enough hands for axe work when needed. If there were four in the party, or if we were making a second ascent of a peak so that only readings and no preparations were needed, one of us would be left behind in base camp to prepare dinner for the others when they returned. When this happened, the task often fell to me as the one to be left behind when the going got rough. Since I was terrified of bears, being left on my own in a small clearing, cooking a supper whose smell could attract bears left me in a perpetual state of fear. The meal often included tinned dehydrated vegetables (I think the make was Bullman’s) — a “delight” that we thought must have been left over from the war. They were so hard that even after being soaked in water all day, they were only just palatable when liberally mixed with gravy from canned beef stew.[8]

The combination of a rainy spring and early summer then a hot later period produced clouds of mosquitos to which I am mildly allergic, each bite swelling up to be much larger and longer lasting than most of the others suffered. Each time we sat down for a rest on our tramp through the rain forest, we were surrounded by a black cloud of mosquitos whose collective noise was almost deafening. We would have a race for all of us to light up cigarettes ASAP, the smoke from which the mosquitos did not seem to like. That gave us at least partial relief.

The large and voracious mosquitos were so bad that after we got into our Egyptian cotton tent each night, we all sat in our sleeping bags and declared war on any flying things in our tent. Usually about ten minutes were required to rid us of all biting bugs, after which we could sleep soundly. But woe betide he who had to heed a nocturnal call of nature. The mosquito guard would quickly alert the rest and, unless the trip outside was quick, our man would be beset by a cloud of them before he could get back into the tent. Fortunately, on the mountaintops where we read our angles and built our cairns, the wind was almost always too strong for the biting hordes of mosquitos.

Our boat only left our area twice, once clandestinely and once officially. The first time, Geoff was left on board while the rest of us went off in our usual two parties to climb our next maintains. Geoff persuaded the captain to take a trip to Zeballos, only a short hop north of our area. This was probably to ease the boredom of sitting around on the boat waiting for the land crews to return. Unfortunately for the two of them, Art on his mountaintop perch saw the ship sailing away from the anchorage where we had left it. When we returned to the boat there was “all Hell to pay.”

The second was later on, I think in late August, when we made a sanctioned trip to Zeballos. I am not sure, but I think it was just a pleasure jaunt with no official business in mind. It was anyway a welcome visit to the civilisation of what was only a very small mining town. I think the picture of the village is of us approaching Zeballos, and I am sure the door to the mining office was at that town.[9]

Every eight days the Princess Maquinna called in to Nootka as part of her West Coast service. We would go on board, buy ice cream and think of home, both on the ship and later sitting on the dock just dreaming. We were usually given a “Sunday” the day the ship came in, if that was at all possible. As well as these on-ship pleasures, we did our washing and other domestic duties on that day.

Other than the Maquinna, the only other way out, except on our own power, was the Stranaer flying boat, a 1930s designed biplane that made frequent trips to the West Coast.

Sometime in mid-July the sun came out and with only occasional rainy days after that, we had some glorious summer days. Then around the end of July, I did something to my back on one of our trips and made a big deal of packing to go home on the next visit of the Princess Maquinna. Fortunately, I changed my mind at the last moment and decided to stay after the Chief, having been alerted to my condition, said I could stay on board during the next sojourn to a new mountaintop.

Sometime in mid-July the sun came out and with only occasional rainy days after that, we had some glorious summer days. Then around the end of July, I did something to my back on one of our trips and made a big deal of packing to go home on the next visit of the Princess Maquinna. Fortunately, I changed my mind at the last moment and decided to stay after the Chief, having been alerted to my condition, said I could stay on board during the next sojourn to a new mountaintop.

In early August the Indians, as they were then called by everyone, invited us to come to their village near Friendly Cove for their sports day. We cleaned ourselves up and spent a lovely day watching all of the exuberant festivities, races of all sorts, tugs of war, and other similar events. This was truly a memorable occasion and we felt honoured that they wanted to share their big day with us.

In mid-August we had to journey far into the interior of our area. All eight of us set out following the bank of the Gold River, each carrying packs containing large amounts of supplies. For once the captain and cook were left alone with no axeman to keep them company. We set up a base camp on the riverbank about a day’s walk from the sea. From there, two crews were able to set out for another day’s trek in two different directions to set up their high camps from which to make their assaults on their mountain the following day.

On one of these I was chosen to go with the Chief’s group. At our high camp I pleaded to be allowed to go to the top while Geoff, who preferred staying in camp, was to be the one left behind to prepare dinner. The Chief did not like this arrangement because, as he said, “You are too slow and will delay us all.” I promised that this would not happen and he relented. To lighten my load he told me to leave my long axe behind and on the top I could borrow his Lady Axe (an axe with a short handle).

I did manage with enormous effort to keep up and not be a drag on the group’s progress. When we reached the top, we had to chop a lot of trees to clear for the usual 360° sightings. When I returned the Chief’s axe to him, it was badly dented across the whole of the blade. I never figured out how that had happened. Maybe there were stones embed in the trees?! He never said a word to me about the state of his axe but it was easy to read his thoughts from the frown in his face: “There Dick goes, screwing things up again; whatever he does, it ends in a mess.”

I think we made about six climbs from this camp on the river using two crews. To cross the river we needed a raft, which we made with trees that we cut, stripped, and tied with some local vines and ropes we had brought from the ship. It was sturdy enough to ferry three of us at a time across the river.

During one of these climbs I was left in the lower camp on the Gold River to prepare supper for both crews when they returned. I spent a lovely day by the river in bright sunshine with the sounds of the river and the forest all around me. I even forgot briefly about my imagined dangers of lurking wildlife. This is the kind of wonderful day one remembers up front while leaving in the back of one’s mind the nights of sleeping in soaking wet bags with matches too damp to even light a fire — the last of which only happened once, but that was enough!

Then sometime in late August, after my aborted idea of going home, and after the Gold River adventure, I had an epiphany. Suddenly I was no longer afraid of rock faces and had found the strength to keep up with the others. Sadly, the Chief and his assistant, Art, did not notice the change. I remember on our last climb to a very high mountain, I told Art that I was no longer afraid of rock faces and now managed to keep up better than the rest. I told him this on a sloping rock face while we waited for the other member of our group to inch his way up to us. Because this was the first mountain they had climbed at the beginning of our adventure, they did not need a third person at the top. Unmoved by my statement, he left me behind at base camp on the last ascent of the year. When they got back late in the evening they were so tired that they just grabbed a bit of the meal I had prepared and had no energy to sit by the fire fed by the large supply of logs that I had cut during the day. Their, to them understandable, rejection of the celebrative evening I had prepared for them was hard for me to take, but I guess it was all part of my learning curve.

Sadly, I never got to persuade the leaders that I had become, over the summer, the stalwart axeman who eventually became the best member of the trail crew in Kootenay National Park over the following two academic summers. There, under the experienced bushman, Austin Plant, who led us, I learned much in my first year on the Park’s trail crew and, by the second year, had become demonstrably the best crew member in ability with an axe and in stamina. But back in the West Coast, even after Art’s rejection, I got an enormous personal charge in knowing that I had gone in one long and eventful summer from a frightened, inexperienced, out-of-condition guy to an experienced and reasonably competent woodsman.

When we all got back to the boat we had a celebratory meal and then the Chief decided to head back to Victoria ASAP in order to be ahead of the dreaded equinoctial gales. On the West Coast these could be devastating to a ship such as ours. So, in mid-September we again rounded Race Rocks, reached Victoria, and disbanded.

Autumn turned to winter and our lives returned to their separate routines, but come Christmas Art had us axemen over for a reunion. A band of comrades once again, we joked and laughed the evening away with many reminiscences of our failures as well as our successes of the previous summer. After that, Alan and I never saw the others, except for Spencer the son of my parents’ friends, and Doc who accompanied me to Kootenay National Park two years later where I was already an experienced senior member of the trail crew in my second summer in that job — but that is another story all together!

*

Richard Lipsey, BA (UBC), MA (Toronto) PhD (University of London, England) was born in Victoria in 1928. His maternal grandfather came to Victoria in the mid-nineteenth century and worked at the 150 Mile House repairing stagecoaches for the BX Express and then partnered a carriage building business in Victoria. His maternal grandmother hailed from Hamilton, Ontario, where her father was instrumental in founding the Canadian Press. A paternal great grandfather emigrated from Northern Ireland to Ottawa where he was gardener to the Governor-General in the 1860s. His father was well known locally as manager of A.P. Slade Wholesale Produce. Emeritus professor of economics Simon Fraser University, Richard Lipsey has held professorships at many universities in the UK, Canada, and the US, and holds nine honorary degrees from Canadian and UK universities. He is author of 200 articles, book chapters, textbooks, and technical monographs. His book Economic Transformations: General Purpose Technologies and Long Term Economic Growth won the 2006 Schumpeter prize in evolutionary economics. He was made was a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada in 1979, and an Officer of the Order of Canada in 1991.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher/Designer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: CreativeBC.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

[1] See Richard G. Lipsey, “Introduction: An Intellectual Autobiography,” in Macroeconomic Theory and Policy: The Selected Essays of Richard G. Lipsey, Volume Two, (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 1997), pp. i-xxii.

[2] https://www.summitpost.org/conuma-peak/423697

[3] Alfred George Slocomb was born in Liverpool, England, and died in Victoria in 1991. Between 1946 and 1948, Lindsay Elms writes, Slocomb was “in charge of topographical control surveys on the west coast of Vancouver Island from Flores Island northwest to Brooks Bay.” In 1948, Slocomb became Chief of the Topographic Division of the B.C. government, a position he held until 1971. See Lindsay Elms’ biography in Beyond Nootka. http://www.beyondnootka.com/biographies/alfred_slocomb.html

[4] See also Katherine Gordon, Made to Measure: A History of Land Surveying in British Columbia (Winlaw: Sono Nis Press, 2006).

[5] This is entirely possible. The American writer Jack London (1876-1916) worked on sealing schooners in the north Pacific in 1893 and took part in the Klondike Gold Rush in 1897-98. London based his character, Wolf Larsen in The Sea-Wolf (1904) on the Nova Scotian sealer Captain Alexander MacLean (1858-1914). See Don MacGillivray, Captain Alex MacLean: Jack London’s Sea Wolf (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008).

[6] This is Hot Spring Cove, about 50 km northwest of Tofino. See: http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/bcparks/explore/parkpgs/maquinna/

[7] http://www.summitpost.org/conuma-peak/423697

[8] See Mary Leah de Zwart, “Bulmans Cannery: The Dehydration Industry in Vernon,” BC Food History Network, May 16, 2017. http://www.bcfoodhistory.ca/bulmans-cannery-dehydration/

[9] Lipsey is correct. His photo of the door of the mining office was indeed taken in Zeballos. A similar photo from 1947, showing postmaster George Nicholson standing in the doorway, is in the BC Archives, Item I-27541. See also George Nicholson, Vancouver Island’s West Coast, 1762-1962 (Victoria: Morriss Printing, 1962), and Alan Twigg, “George Nicholson,” BC Booklook, January 26th, 2016, https://bcbooklook.com/2016/01/26/75-george-nicholson/

Leave a Reply