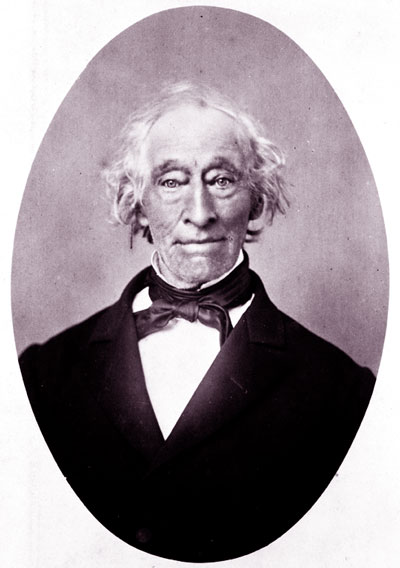

#174 John Tod

March 09th, 2016

LOCATION: Tod House, 2564 Heron Street, Oak Bay.

One of the oldest surviving houses in Western Canada was built by John Tod, one of the first important fur traders in British Columbia in New Caledonia, an area that included Fort Alexandria, Fort St. James, Fort Fraser, Fort George, McLeod Lake, Fort Babine and Fort Connolly. Once described as a man “of excellent principle, but vulgar manners,” John Tod wrote the History of New Caledonia and the Northwest Coast, the obscure forerunner to A.G. Morice’s better-known The History of the Northern Interior of British Columbia, Formerly New Caledonia, 1660–1880. In a letter to James Hargrave in 1843, he once wrote, “Unfortunate Fur Traders, how few of you are doomed to taste the sweets of civilized life.” In order to control the influx of mostly American miners to the Cariboo gold fields, the Colonial Office in London annexed the New Caledonia Department within its new Crown Colony of British Columbia in 1858.

ENTRY

The first-born in a family of nine children, John Tod was born near Loch Lomond, Scotland, in 1794. He grew up west of Glasgow on the banks of the Leven River and left school at sixteen to work in Glasgow in the textile industry, in a cotton warehouse. He lost his position at eighteen when he refused to accept a double workload without adequate compensation.

Unemployed and at odds with his parents, Tod signed a five-year contract to work as an apprentice clerk for the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1811. With copies of Robbie Burns’ poetry, Buchan’s Domestic Medicine and the Bible, he sailed on the Edward and Ann to York Factory on Hudson Bay. He was sent as a greenhorn to Fort Severn, where he wintered. Enduring much privation, he learned “Swampy Cree” for two years, then was transferred to oversee Island Lake and York Factory in succession.

John Tod was present in the mess hall at York Factory in the summer of 1821 to witness the dinner hosted by thirty-four-year-old George Simpson to unite the apprehensive traders of the Nor’westers with their new HBC partners after the formalized merger of those two companies on March 26, 1821.

Tod wrote: “Evidently uncertain how they would seat themselves at the table, I eyed them with close attention from a remote corner of the room, and to my mind the scene formed no bad representation of that incongruous animal seen by the King of Babylon in one of his dreams, one part iron, another of clay; though joined together [they] would not amalgamate, for the Nor’westers in one compact body kept together and evidently had no inclination at first to mix with their old rivals in trade.”

Tod wrote: “Evidently uncertain how they would seat themselves at the table, I eyed them with close attention from a remote corner of the room, and to my mind the scene formed no bad representation of that incongruous animal seen by the King of Babylon in one of his dreams, one part iron, another of clay; though joined together [they] would not amalgamate, for the Nor’westers in one compact body kept together and evidently had no inclination at first to mix with their old rivals in trade.”

Governor Simpson reputedly disliked Tod and sent him to New Caledonia in 1823. Tod initially joined James Murray Yale for one year at Fort George (Prince George, B.C.) before his posting at Fort McLeod. In the winter of 1825 and the spring of 1826, Tod was joined by an up-and-coming HBC employee named James Douglas.

Isolated and lonely at Fort McLeod, unable to speak English to anyone, Tod read a great deal and appreciated the companionship of “the singing girl” who he avowed was “possessed of excellent ear for music & never fails to accompany me on the Flute with her voice when I take up the instruments.” This was the first of John Tod’s country wives.

Tod wrote to Edward Ermatinger about her in 1829: “You ask what is become of the girl who used to sing at McLeods Lake. I have a good mind to answer You as Mr. Boulton, our old messmate, would do but I have not his taste for smut unless it is wraped [sic] up in clean linen — Why then in plain language she still continues the only companion of my solitude — without her, or some other substitute, life, in such a wretched place as this, would be altogether unsupportable.”

John Tod resolved to quit the HBC after nine years in New Caledonia and started back to Scotland, only to receive long-awaited news that he was promoted to the rank of officer in the company. Having received his commission in 1834, Tod was granted a one-year leave. Sailing from Hudson Bay on the Prince Rupert, he met a governess, Eliza Waugh, whom he soon married in England.

The couple did not live happily ever after. In 1835, the Tods went to Rupert’s Land via New York, then waited in the Red River District for Tod’s new posting at Island Lake where Eliza suffered a mental breakdown in 1837. He took her to live with relatives in Wales, then returned to work in New Caledonia and at Fort Vancouver, Fort Alexandria (1839–1842), Kamloops (1842–1849) and Fort Nisqually on Puget Sound.

Legend has it that while working at the Kamloops site—first seen by traders of the Pacific Fur Company, then developed by the North West Company, then controlled by the HBC—John Tod was deemed “impossible to kill” by the local Aboriginals.

In 1846, upon being notified by the fort’s interpreter Lolo of a planned attack, Tod showed his mettle by riding forth on a white mare to meet a war party of more than one thousand Aboriginals on the banks of the Fraser River. Tod informed them smallpox had broken out at Walla Walla and he had come to vaccinate them. “I commenced to cut & vaccinate,” he recalled, “those who were more noted rascals than others I laid into with a vengeance.” The would-be attackers retreated with sore arms.

Tod, in poor health, retired to a large property in Oak Bay, near Fort Victoria, in 1850, which he called Willows Farm, whereupon the first governor of the Colony of Vancouver Island, Richard Blanshard, appointed Tod to serve on the colony’s new executive council in 1851. There were only two other members: James Cooper and James Douglas. Tod, in effect, became one of the four most powerful men on Vancouver Island.

With its loyalties to the Hudson’s Bay Company rather than the Crown, the new council made life difficult for Blanshard, who suffered from “neuralgia” (he drank) and was undermined at every turn by Douglas. After Douglas replaced Blanshard in September of 1851, thereby securing colonial control for the Hudson’s Bay Company, John Tod officially retired from the HBC on June 1, 1852. To outnumber the independence of councillor James Cooper, Douglas added two HBC sympathizers, Roderick Finlayson and John Work, to support Tod’s HBC bias. Tod served as a Justice of the Peace, resolving disputes for one pound per day, and helped pass the first liquor tax in B.C.

Retiring from the council in 1858, Tod lived in Oak Bay where he played the flute and fiddle, enjoyed nature and recalled an unconventional life. In his retirement, he also produced his New Caledonia history, one of the earliest documents pertaining to the interior of B.C. The family inhabited the house until 1890. According to Canada’s Historic Places:

“The house is a rare and intact example of the French Canadian style, piece-sur-piece construction, which was used extensively by Hudson’s Bay builders across Canada. Built in three sections, the transition from pioneer homestead to permanent residence is illustrated by the evolution of building technologies, from the 1850-52 log construction to the 1860s frame construction addition.

“Tod’s farm is important as one of five properties that comprise the first subdivision of HBC land in Oak Bay. Sold with the approval of Sir James Douglas on behalf of the HBC and surveyed by J. D. Pemberton, the devolution of HBC property followed the decline of the fur trade on Vancouver Island. The location of Tod House, in close proximity to the waterfront and its relationship to Cadboro(ugh) Bay Road via Tod Road, illustrates the important link between early urban development and the two historical transportation routes connecting the HBC farm with Fort Victoria.”

Tod had one son named James with his first country wife at York Factory, Catherine Birstone, and at least one child with his second country wife at Fort McLeod. One child was born to Eliza (Waugh) Tod, then he had another seven children with Sophia Lolo whom he met at the Thompson’s River Post (Kamloops). After receiving news of Eliza’s death in 1857, Tod married Sophia in 1863.

John Tod’s opinions of so-called half-breeds were summarized in a letter to Edward Ermatinger in 1843: “Well have you observed that all attempts to make gentlemen of them, have hitherto proved a failure. The fact is there is something radically wrong about them all as is evidently shown from mental science alone, I mean Phrenology, the truths of which I have lately convinced myself from extensive personal observation.”

In his writing, Tod did not entirely approve of the Hudson’s Bay Company practice of enacting the death penalty without a proper trial: “I knew that it was illegal, strictly, for I had seen at York Factory the British Parliament Act.”

John Tod died on August 31, 1882. Tod Mountain near Kamloops, and Tod Inlet northwest of Victoria, bear his name.

BOOKS:

Tod, John. History of New Caledonia and the Northwest Coast. (National Archives of Canada, Ottawa, 1878).

ABOUT JOHN TOD:

Belyk, Robert. John Tod: Rebel in the Ranks (Horsdal & Schubart, 1995).

Leave a Reply