Those were the days, my friend

At age 24, Mona Fertig opened The Literary Storefront.

November 17th, 2015

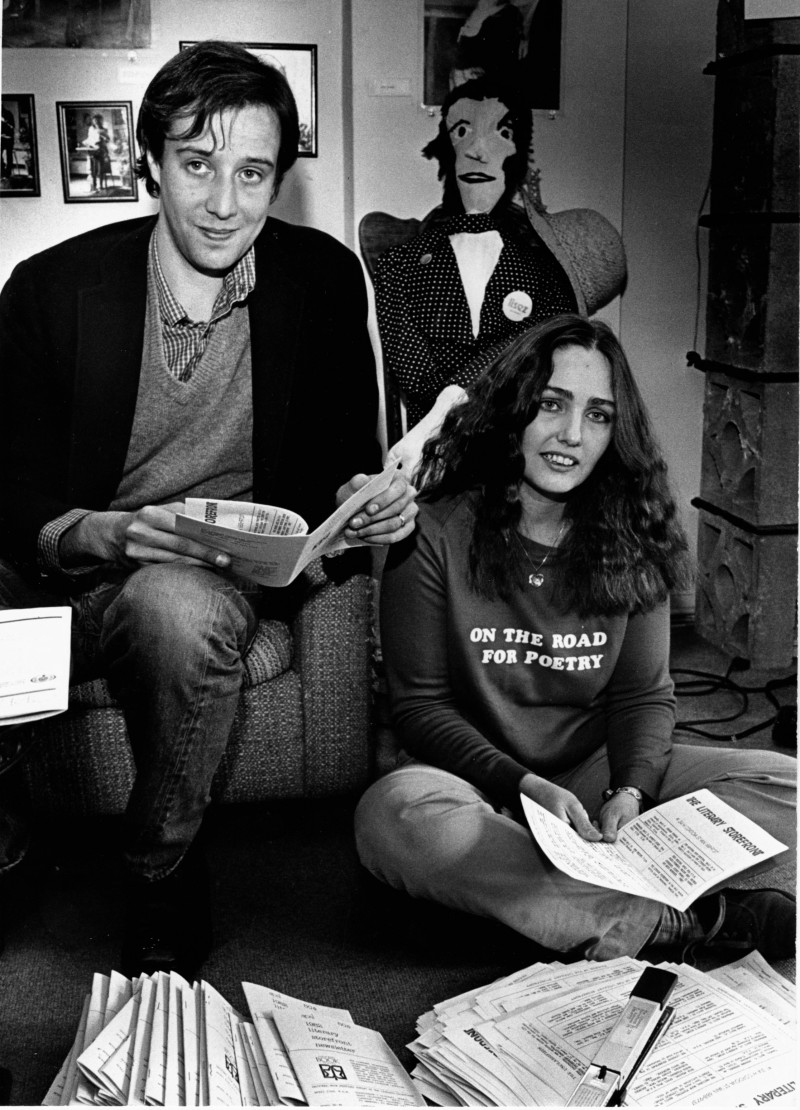

Peter Haase and Mona Fertig when the Literary Storefront opened; now they're book publishers.

Trevor Carolan ensures acquaintances will not be forgot with The Literary Storefront, The Glory Years, Vancouver’s Literary Centre 1978-1984.

In October of 1980 , The Writers’ Union of Canada-BC Branch, The League of Canadian Poets and The Literary Storefront had put in a group application to the BC Cultural Fund for the amount of $25,000 to run the Literary Storefront as a Literary Centre. A broad swath of provincial, regional and community literary organizations, as well as individuals, rallied in support of the cause.

Those were the days, my friend.

The goal was to provide co-operative programs with literary groups such as TWUC, the LCP, PWAC, The Guild of Canadian Playwrights, The Canadian Book Information Centre, The Association of Book Publishers of B.C. (ABPBC), The Canadian Authors Association (CAA), The Burnaby Writers Society, The Richmond Writers Group, The Association of English Teachers of B.C., The C.P.P.A. and more. A bunch of people wrote letters of support including Paulette Kerr, Regional Director of the Canadian Book Information Centre, Lorna Farrell-Ward, former Curator at the Vancouver Art Gallery, Linda Turnbull, Director of the ABPBC, Leonard Angel, BC Rep of the Guild of Canadian Playwrights, Eleanor Wachtel, Vice-President of the Canadian Periodical Publishers Association (CPPA), and the Vancouver Public Library and many more.

The goal was to provide co-operative programs with literary groups such as TWUC, the LCP, PWAC, The Guild of Canadian Playwrights, The Canadian Book Information Centre, The Association of Book Publishers of B.C. (ABPBC), The Canadian Authors Association (CAA), The Burnaby Writers Society, The Richmond Writers Group, The Association of English Teachers of B.C., The C.P.P.A. and more. A bunch of people wrote letters of support including Paulette Kerr, Regional Director of the Canadian Book Information Centre, Lorna Farrell-Ward, former Curator at the Vancouver Art Gallery, Linda Turnbull, Director of the ABPBC, Leonard Angel, BC Rep of the Guild of Canadian Playwrights, Eleanor Wachtel, Vice-President of the Canadian Periodical Publishers Association (CPPA), and the Vancouver Public Library and many more.

Sandy Frances Duncan (TWUC Rep) and Mona prepared the application. The first Board of Directors of the Literary Centre would be; Sandy Frances Duncan (BC Rep, TWUC), Robin Skelton ( BC Rep, LCP), Paulette Kerr (Regional Director-CIBC), Scott McIntyre (Publisher), Margaret Hollingsworth (BC Rep Guild of Canadian Playwrights). Administrative Staff would be Mona Fertig, Founder and Executive Director of the Literary Storefront and Ingrid Klassen, Executive Director of the BC Branch of The Writers’ Union of Canada.

And lo, it came to pass.

Inspired by the the Shakespeare and Company bookstore in Paris, The Literary Storefront operated in Vancouver’s Gastown district from 1978-84, mostly fueled by Fertig’s enthusiasm. But it began to sputter. The reins were handed over to Tom Ilves, who disappeared long long afterward–only to resurface as the long-serving president of Estonia (he’s still in office).

Now Fertig has commissioned Trevor Carolan to write The Literary Storefront, The Glory Years, Vancouver’s Literary Centre 1978-1984 (Mother Tongue) with a preface by Jean Barman. It includes 130 b & w photographs and images. Concurrently, Fertig has been a tad miffed to learn that an initiative to get major bucks for a new Vancouver-based Literary Arts Centre has claimed in its literature that: “…there has never been a public space to showcase the city’s extraordinary practictioners in the written arts until now… The proposed literary arts centre for Vancouver will be the first of its kind in the city…”

Ahem.

The City of Vancouver has allocated millions of dollars of support to the Vancouver Writers Festival to mostly bring writers to the city from elsewhere–thereby reinforcing the notion that the best writing is done somewhere else–so the hugely productive ‘local’ B.C. literary world deserves some reciprocal support. Two years ago, representatives of Pacific BookWorld News Society went to the City of Vancouver’s cultural funding department and gave ’em hell, having analysed the culture funding budget to discover less than 2% of their arts funding went to literary arts.

So there’s a pretty good chance that the proposed Literary Arts Centre will get off the ground.

All of which can amount to progress. As long as history is not erased in the process.

HERE THEN IS TREVOR CAROLAN‘S FOREWORD TO THE GLORY YEARS OF FERTIG’S STOREFRONT INITIATIVE THAT FALTERS SOON AFTER SHE PASSED IT ALONG TO OTHERS.

—

Introduction

Founded by Mona Fertig, a Vancouver poet, the Literary Storefront thrived in Vancouver from 1978 to 1984. A unique literary centre and cultural institution, it was situated in the historic Gastown area near the Pacific Coast city’s inner harbour waterfront. During its heyday, the Storefront had some 500 members—poets, playwrights, novelists, readers, editors, publishers, journalists, teachers and everything in between—and during its first two years alone drew more than 13,000 people to its diverse events, as well as for its lending library of 2,000 books—often signed—by mainly Canadian authors. People gravitated here for individual reasons—to meet, talk and learn about writing, publishing and the world of books and literature. Some came for comradeship and open-access solidarity; many came simply to see and hear or rub shoulders with an amazing range of established literary personalities. The Literary Storefront’s hundreds of public readings and workshops drew, among other notables, Margaret Atwood, Michael Ondaatje, Dorothy Livesay, Jane Rule, Al Purdy, Earle Birney, bill bissett, Audrey Thomas, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, P.K. Page, Stephen Spender, Edward Albee and Elizabeth Smart. It was a home-port reading base too for the West Coast’s own growing legion of writers: Roy Kiyooka, Susan Musgrave, Keith Maillard, Carolyn Zonailo, Maxine Gadd, Peter Trower and scores of others were familiar headliners. Yet the Literary Storefront was never about simply readings, performances or any one thing. Canada had seen nothing quite like it previously, nor has it since.

This book of oral history and archival research recounts the visionary Literary Storefront project begun by Fertig—the daughter of Vancouver painter George Fertig—that was continued for a time by a collective and a pair of migrant Americans, Wayne Holder and Tom Ilves, the latter who would emerge surprisingly on the world political stage years later as the President of Estonia.

Preliminary work toward this project began with a “brief history” chapbook produced by Mona Fertig for the Reckoning ’07 Conference organized by Alan Twigg at Simon Fraser University’s downtown Vancouver campus. The conference focused on the past and future of British Columbia writing and publishing. Aware that the Literary Storefront’s history had disappeared, Mona gave out the limited edition chapbook to various B.C. publishers and attendees during the coffee breaks. It became clear to a number of veteran British Columbia writers during this event how significantly the region’s literary culture was being academized and, simultaneously, how much of that history was already being lost within this institutionalization. Elders of the West Coast’s literary tribe were steadily passing away.

When Fertig published her own book about her father (The Life and Art of George Fertig) as the third in Mother Tongue Publishing’s Unheralded Artists of BC series, it was not difficult to observe that the memory of the Literary Storefront itself was fading in the same romantic twilight. I knew a number of the artists cited in her book and saw that they too, like veteran writers associated with the 1950s and ’60s, were vanishing stories. As if in confirmation, two feasibility studies for an ambitious and expensive Literary Arts Centre for Vancouver developed by the Association of Book Publishers of B.C. and its supporters makes no reference to or recognition of the history of Vancouver’s first grassroots literary centre; so, this book will serve as a necessary archival document for students of BC’s literary history.

I’d had my own start as a serious writer during the heyday of the old Storefront after returning to Vancouver from several years in northern California. When I began asking old friends and colleagues about their recollections of the Literary Storefront, this led organically to inquiries among an even wider circle of writer contacts. Literally everyone I spoke with recalled the centrality of the Storefront years as a unique moment in the West Coast’s literary and cultural history.

As the nature and scope of the conversation grew, the essential nature of the Literary Storefront began to assert itself again. For almost everyone, the Storefront had been more than just a stop on the path to establishing a career. It had served as a society of friends; some attended readings and workshops regularly for the conviviality and networking opportunities it offered, others were more single-minded regarding their own work and picked selectively at the cornucopia of events on a year-round basis. If, like most of those who congregated there, you didn’t have a lot of money in your pockets, that was all right too; for a time, this was Vancouver’s bohemian consular centre. If you wanted to know about the Zen of writing, to get your mojo working at a first open-mic reading, to engage in searching deliberations with other fledgling writers or to read their work from the shelves of books along the wall—this was the place for you.

During the run of the Literary Storefront, Vancouver was still an old-school seaport town. The World Expo of l986 that would accelerate the demolition of heritage buildings and change the city’s architectural face irrevocably had yet to happen. Downtown, the Hastings Street tenderloin, if rugged, was not the combat zone the provincial and city authorities would allow to fester there; it still housed the city’s best newsagents, a variety of colourful pawnshops, Gabor the Cobbler and the landmark Only Seafood Café. Nearby, Chinatown was still thriving, and the back-alley Green Door and Red Door Restaurant and B.C. Royal Café on Pender Street were old reliables. The Ho Ho at East Pender and Columbia Street remained the city’s unofficial late hours eatery for musicians and jazzoids, and two short blocks away Vie’s nine-table Chicken and Steak House at 209 Union Street still had legs until 1979, serving up what locals could relate to as soul food had survived from 1972 onward.

It wasn’t perfect, but Vancouver was a town of possibility. Architect Arthur Erickson had earned international renown. Bill Reid was associated with the Pacific Northwest Coast’s native art renaissance. Jean Coulthard was a nationally important composer, and B.C. poet Phyllis Webb was an equally respected radio broadcaster. Painter Joe Plaskett, although long a resident of Paris, still called the old capital city of New Westminster, a drive up Kingsway, home, as did novelist Sheila Watson and longtime Perry Mason television series star Raymond Burr. Actor Chief Dan George from the Tsleil-Waututh reserve in North Vancouver had already become a beloved elder to many Canadians, and Bruno Gerussi starred in what seemed like a never-ending hit playing a drift-log salvager in the weekly cbc-tv series The Beachcombers. That Jimi Hendrix’s grandmother Nora had worked as a chef at Vie’s Chicken and Steak place for years while living on East Georgia Street in the nearby Strathcona district, and that her guitar wizard grandson had stayed with her many times and sharpened his chops at Monday night sessions in the clubs around the corner, only added to the sense that this was a place that had known famous times, sprung some big names, that things could happen here. Among writers, Malcolm Lowry had spent the better part of fifteen years nearby, struggling with the making of his celebrated novel Under the Volcano and a series of cloudy follow-ups. Poet Earle Birney had established the country’s first serious creative writing program out at the University of BC (UBC), and Marya Fiamengo, an ardent nationalist, had established a feminist ethic in poetry from the early 1960s onward and was outstandingly supportive of other writers. English professor Warren Tallman from the same school had been instrumental in inviting writers from the American Black Mountain and beat spectrum to the city for almost two decades, as well as shepherding a group of former students into teaching and media careers of significance. Novelist Margaret Laurence and future Nobel Prize winner Alice Munro both lived and worked in the city during formative stages in their careers, while the luminous Ethel Wilson wrote for decades from her home overlooking English Bay. An active theatre community produced an impressive roster of actors and directors.

The late 1960s through to the 1980s was a time of Pierre Trudeau-era nationalist arts funding to Canadian publishers, and British Columbia had a budding regional literary and publishing scene, which included Intermedia Press, Sono Nis (Victoria), New Star Books, Pulp Press, Talonbooks, Commcept Publishing, Orca Sound Publishing, Hancock House, Harbour Publishing, Oolichan Books, Riverrun Books, Vancouver Community Press, blewointment press, as well as an emerging group of women who were starting their own writing/literary businesses. Carolyn Zonailo writes:

A real growth spurt in literary and publishing and printing activities was initiated by women in Vancouver. Caitlin Press was founded by myself in 1977; The Literary Storefront in 1978; Press Gang Printers & Publishers in 1975; and the literary magazine A Room Of One’s Own was founded by a collective of women in 1975. These new literary and publishing enterprises initiated by women complimented [sic] those literary small presses and endeavours begun a few years earlier by male literati such as Very Stone House founded by Pat Lane and Seymour Mayne; Blackfish Press founded by Allan Safarik and Brian Brett, among others.4

In step with Vancouver’s emerging non-academic growth in literary publishing was its downtown pulse. Pulp Press had an office up the street from what would become the Literary Storefront’s Gastown central location; Press Gang was not far off, nor was Cobblestone Printing. Cathy Ford recalls that since the early 1960s, poet bill bissett had been running blewointment press “from a secret location, collating on his living room floor, or conducting contract talks from the nearest phone booth. Some of his best contracts were written on postcards, and he sought out and published many new, especially downtown, poets.” Downtown Eastside poet Gerry Gilbert’s mimeographed B.C. Monthly

Vancouver remained a swinging, neon town, renowned among North American musicians for the high tenor of its talent and nightlife. The Main Street and Hastings cabaret district that sent acts like Cheech and Chong, Bobby Taylor and the Vancouvers and others to stardom was entering its last stand. The Lotus Hotel across the road from the old Vancouver Sun building at Pender and Abbott remained a favourite media watering hole, and up-and-coming writers still hoped to meet veterans like the Vancouver Sun’s Allan Fotheringham, Jack Webster and Marjorie Nichols there from time to time. Five minutes’ walk away, the north end of Granville Street retained its colonial-era atmosphere with fine tailors, upscale shoe emporia, James Inglis Reid’s grand old British butcher shop and Woodwards’ $1.49 day. Free parking in the immediate area was an inducement to downtown shoppers.

Bookshops meanwhile, new and used, flourished. Duthie’s, MacLeod’s, Colophon, Richard Pender Books and the leftist outlet Spartacus were all in bloom. For bohemian die-hards, the Classical Joint on Carrall Street was the town’s perennial evening-until-late jazz nexus. A handful of Irish pubs and run-of-the-mill watering holes opened early for the area’s large population of single-room occupants—old loggers, fishermen, boom-men, miners and sundry veterans who’d somehow slipped through the social net. Working-class, shake and shimmy, down at heel, creative and cheap, the Gastown-Downtown Eastside district was a natural magnet for the young and artistic with a dream, and for outsiders of every social hue. It was the ideal location for a walk-in literary centre. It still is.

Novelist David Watmough reflects:

I’m eighty-seven and we’re talking about thirty or more years ago, but my overall impression of Vancouver during the period of the Literary Storefront is that, until then, how lonely and isolated we were as artists and writers here… There was a pervasive sense of remoteness, and the atmosphere between the West and the East was quite hostile. You had the counterculture and the Peace Movements, but everything from Toronto came a week late in the mail. And literature never got quite the thrust that the visual arts did… We had various little power circles here—UBC, the CBC, they were sources of money… Even within our own literary tribe there were lots of little tribes.

Poet Cathy Ford adds:

When I came from the far north as a Creative Writing student at UBC, I suffered various types of culture shock… there were warring factions in literary Vancouver. Literally, people who were rude to one another, gossiped loud and long about each other, and never invited one another to read at or attend readings. The academic centres were most easily identifiable for these sins…UBC, SFU, Capilano College, Douglas College, VCC, and the library system all overlapped one another. Meanwhile, experimental and profoundly exciting things went on downtown, in various art galleries, in Kitsilano, at bookstores and storefronts, at Western Front in combined art and literary openings, and political actions. The most challenging, progressive written work and broadside, chapbook or book publication was being done outside the formally identifiable affiliations. For someone eager to experience a sense of community, I had a lot to think about in terms of inclusiveness, personal and professional conduct, integrity.

My own encounter with the Literary Storefront came by word of mouth. I was riding in a car downtown, crammed among new faces after reconnecting on the Royal City’s running trails with Ron Tabak. We’d been schoolmates, and he’d gone on to pop stardom as the magnetic singer with Prism, one of Vancouver’s first international rock acts.

Ronnie and I ran long-distance in high school. Tall and lean, he’d always been a little faster than I was. Ronnie stuttered, but he let his hair grow long and could shake it; when he belted out a chart-busting tune like “Armageddon,” all the glitches disappeared, and you knew you were listening to a real star. Ronnie lived the pop world high-life for a few years. I’d seen his posters for a huge concert in New York’s Central Park when I was out on the road myself, hustling readings back east. His gold records had that sparkle dust up on the wall at his place up the road.

Now we were in a car full of Ronnie’s pals, jamming out the windows. Susie Whiten, a blues singer, asked who I was. Flipping my notebook to the poems I wrote to keep myself sane in a heavy day job, I said I was a writer. Susie reached through the mob for a scan of my lines.

“You oughta get down to the Storefront and read these,” she said.

“What?”

“The Literary Storefront, in Gastown. My friend Mona runs it. Go down to an open-mic session, listen to other poets, get up and read your stuff, two or three poems like these. See what people think.”

One Sunday, I took Susie’s advice. The first thing you noticed after you climbed the stairs in Gaslight Square at 131 Water Street was the Storefront’s brickwork, funky and kind of comfy like North Beach near City Lights in San Francisco. People read in turn; there were a lot of women. I waited, listening. Nobody got put down. When I was invited up, it all went fine. People offered polite applause. At 27, it was my first public reading in town.

During a break, someone explained that it was a women’s group reading—feminists and lesbians. In my newness, my enthusiasm, I’d missed all that. When I’d given my name to read, someone had simply noticed that I’d travelled some distance, and they’d been decent enough to give me a shot. When the penny dropped, I smiled at their kindness, nodded in thanks and left soon after. I would return many times.

For young writers like me, the Literary Storefront was an unofficial, post-graduate education centre. It was where a generation of Vancouver writers, surfing somewhere between the nationalist and the as-yet-unformed multicultural waves in CanLit, could learn how the writing and publishing game ticked. It was a chance to become part of a community—and by the late 1970s, there was a constituency in Vancouver that needed precisely this. At the same moment, in the Smiling Buddha or any other rundown club that would have them, a similar generation of young punk rockers was figuring out the music world, and a new wave of young painters and sculptors were reimagining their creative missions in the common, low-rent environments of Gastown, Chinatown and the Downtown Eastside. Meantime downtown, the Vancouver School of Art still featured some writing-related events, readings and talks, while the Alcazar Hotel, growing seedy at the corner of Dunsmuir and Homer, was a particular favourite watering hole of the town’s creative arts community. The Video Inn at 261 Powell Street hosted events as well.9A few blocks north brought you to the 1950s Vancouver Art Gallery on 1145 West Georgia Street where literary events such as the memorable reading by Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko took place in 1974.

Against this background, in 1978 the Literary Storefront would emerge right out of the starting blocks as an incubator for the literary arts in a Pacific Coast town that had long been devoted more to hard work and real estate speculation than literature. Devoted to writers and writing, high-brow literary theory from Paris and East Coast universities never transplanted well in the Literary Storefront’s earthy, practical loam. If there was intellectual debate, it was on couches during random drop-in sessions with friends or strangers met while perusing the bookshelves or the framed ephemera on the walls. More likely, it was during or after a reading or workshop presentation. The Storefront hosted literary and arts events and endured financial wobbles of every sort, not uncommon for most non-profit arts organizations. That’s what made the place as likeable as it was. It was the Gastown donkey engine in the West Coast’s arts scene, chugging along indomitably toward the Word, the Sound, the Beat. Ironically, that wasn’t far from the mission that its founder Mona Fertig, a working-class poet and young literary organizer from Burnaby, had envisioned when she realized what she could do now that she’d grown up. Here then, is the way it was at the Literary Storefront, when in the pursuit of happiness, Mona Fertig, Vancouver’s legendary unaffiliated literary force, hung out her shingle at age twenty-four and single-handedly got Vancouver’s writing and literature jumping in a whole new way. It was a courageous idea and enormous accomplishment for a young woman whose life so far, while rich in art and creative inspiration, had flirted around and faced down the poverty line. Heaven only knows what so many of us in the West Coast’s writing community would have done without it.

Hail to the Muse,

Trevor Carolan, Vancouver 2015

What an exciting read. Would love to have been part of that crowd but I wasn’t writing back then. And now as an older writer I wonder how different things are now in the writing world of newcomers and self publishers. Interesting to contemplate. Look forward to reading the book.