Ryga Award shortlist announced

The George Ryga Award for Social Awareness highlights First Nations, drug addiction treatment and the environment.

February 21st, 2018

Insite founders Ann-Livingston and Bud Osborn are featured in Travis Lupick's Fighting for Space.

Shortlisted titles are Gary Geddes’ Medicine Unbundled, Travis Lupick’s Fighting for Space and David Suzuki & Ian Hanington’s Just Cool It!

Last year’s Ryga Award recipient was Wade Davis for Wade Davis, Photographs.

The shortlist for the 2018 George Ryga Award for Social Awareness is:

Gary Geddes: Medicine Unbundled: A Journey through the Minefields of Indigenous Health Care (Heritage House, 2017).

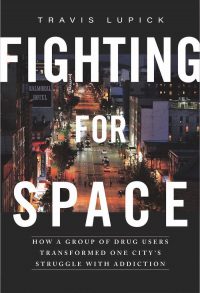

Travis Lupick: Fighting for Space: How a Group of Drug Users Transformed One City’s Struggle with Addiction (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2017)

David Suzuki and Ian Hanington: Just Cool It! The Climate Crisis and What We Can Do (Greystone, 2017).

This year’s Ryga Award presentation ceremony will be held at the main branch of the Vancouver Public Library on Thursday, June 28th.

*

ORMSBY REVIEW HAS ALREADY FEATURED REVIEWS OF MEDICINE UNBUNDLED AND JUST COOL IT!

HERE IS A REVIEW OF THE THIRD SHORTLISTED TITLE.

Fighting for Space: How a Group of Drug Users Transformed One City’s Struggle with Addiction

Travis Lupick

Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2017.

$24.95. / 9781551527123

Reviewed by Danya Fast

One of the three titles shortlisted for this year’s George Ryga Award for Social Awareness, Travis Lupick’s Fighting for Space: How a Group of Drug Users Transformed One City’s Struggle with Addiction, is a suprisingly in-depth documentation of how and why Vancouver became a world leader in finding new ways to recognize and cope with drug addiction.

One of the three titles shortlisted for this year’s George Ryga Award for Social Awareness, Travis Lupick’s Fighting for Space: How a Group of Drug Users Transformed One City’s Struggle with Addiction, is a suprisingly in-depth documentation of how and why Vancouver became a world leader in finding new ways to recognize and cope with drug addiction.

For Lupick, living for years on the Downtown Eastside, has been akin to being an embedded journalist reporting to a world that maintains a superficial knowledge of a war that is largely being waged to gain dignity against those whose primary values are property values.

A review of this book by freelance journalist David Conn will also be featured in the forthcoming Spring issue of B.C. BookWorld.–Ed.

*

Locally and globally, Vancouver is celebrated for its world-class harm reduction and social housing programs, and regarded as a model for other cities beset by the problems of homelessness and addiction.

Today, initiatives like low barrier supportive housing, widespread needle distribution, and North America’s first legally sanctioned supervised injection site (known as Insite) have become incorporated into the city’s mythology.

As harm reduction has become a part of the story that the city of Vancouver likes to tell about itself, the fierce battle for these policy reforms waged by people who use drugs and their allies throughout the 1990s and 2000s has perhaps receded from the public imagination.

In Fighting for Space: How a Group of Drug Users Transformed One City’s Struggle with Addiction, journalist Travis Lupick tells the story of those individuals who, in response to the HIV/AIDS and overdose epidemics of the 1990s, came together to demand life-saving services and spaces for people who use drugs in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

Lupick’s account is richly researched and profiles a large number of the people involved in the founding of the Portland Hotel Society and Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU), and the eventual establishment of Insite in 2003.

Particularly nuanced are Lupick’s portrayals of VANDU founders Bud Osborn and Anne Livingston, former VANDU president Dean Wilson, and Portland Hotel Society founders Liz Evans and Mark Townsend, which he develops across a number of crystallizing moments in the harm reduction and housing movements.

These include the opening of the original Portland Hotel in 1991 (a home of “last resort” for Downtown Eastside residents living with substance use and mental health issues); the establishment of three unsanctioned supervised injection sites prior to the opening of Insite; and the 1997 Killing Fields protest, during which one thousand white crosses were erected in Oppenheimer park to symbolize the number of lives lost to drug overdose and HIV/AIDS in the neighboorhood.

Fighting for Space is an engaging and accessible read. Speaking as an anthropologist who has been doing research in the Downtown Eastside for the past decade, and as a member of the team of researchers who conducted the scientific evaluation of Insite, I finished the book with a much fuller picture of, and appreciation for, this extraordinary story of grassroots activism. Fighting for Space will have popular appeal, but it would also be suitably assigned to high school and undergraduate classes as way of introducing students to contemporary issues in public health, social justice, and urban governance.

Lupick only spends one chapter on the 2014 financial scandal at the PHS and subsequent dismantling of the society’s management team, during which Evans and Townsend were forced to step down. Publicly, this dismantling was attributed to the damning findings of a financial audit. However, as Lupick details, this was also a political “assassination” of sorts, which ensured that the PHS’ “activist days were over” (p. 368).

Here Lupick stops short of broader reflections on how harm reduction in Vancouver’s inner city has gradually shifted from an oppositional, activist platform for addressing the material conditions that frame drug-related harms, to a more apolitical platform for managing health and public disorder within “risky” populations and places.

Given the title of the book, also conspicuously absent are broader reflections on how the accelerating gentrification of the Downtown Eastside has impacted the “fight for space” among the neighbourhood’s most marginalized residents, and how easily harm reduction can slip into poverty management, “disappearing” unruly bodies into supportive housing and injection sites in the service of urban revitalization.

Understandably, many journalists and researchers avoid these kinds of more academic critiques for fear that they might embolden conservative agendas that would further strip away social and health services for the poor. However, critiques of harm reduction also come from people who use drugs, including those in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

For instance, as one young man explained to me in 2012, when I asked him why he had decided to quit the SALOME prescription diacetylmorphine (heroin) trial: “I don’t want to be a drug addict. I didn’t like the fact that [the people who ran the trial] were just giving us dope, and I didn’t like the fact that they had to watch our every fucking move every fucking minute we were in there.”

Harm reduction and supportive housing interventions save lives, and the intrepid individuals who fought for their establishment in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside should be celebrated. I am questioning whether there is room in stories like the one Lupick tells for these more ambivalent and critical voices, which come from both inside and outside of the Downtown Eastside.

We also need to ask important questions about how harm reduction and housing interventions are being implemented. What was the original vision for these services and spaces, and how has that vision been transformed across time, including by events like the restructuring of the PHS? Fighting for Space ably answers the first question, but leaves the second unanswered.

Lupick concludes the book with a chapter on the arrival of fentanyl in 2011, and an unprecedented opioid overdose crisis that has resulted in more than 2000 deaths in British Columbia since 2016. Once again, Downtown Eastside residents and their allies have mobilized by setting up overdose prevention tents and patrols, and trying to get as many people as possible trained in the administration of naloxone (the overdose antidote). The provincial government followed their lead in late 2016 by dispatching a mobile emergency room to the Downtown Eastside and opening more than fifteen new overdose prevention sites.

However, Lupick argues that a response to the current crisis based on harm reduction, “while important, is entirely reactive; it’s only reaching people after they’ve already ingested drugs that are potentially deadly” (p. 375). A more viable solution, he suggests, is the scaled up provision of prescription heroin for anyone at significant risk of a drug overdose. His suggestion was prescient, as this drug policy shift is imminent in British Columbia.

However, Lupick argues that a response to the current crisis based on harm reduction, “while important, is entirely reactive; it’s only reaching people after they’ve already ingested drugs that are potentially deadly” (p. 375). A more viable solution, he suggests, is the scaled up provision of prescription heroin for anyone at significant risk of a drug overdose. His suggestion was prescient, as this drug policy shift is imminent in British Columbia.

It is in the epilogue that Lupick’s hits beautifully on another crucial part of the “solution” to the overdose crisis, when he describes how one family benefited — across three generations — from the different kinds of spaces created for them by Evans, Townsend, and the PHS. This included spaces in which to live, but also spaces in which to work, get married, and have children.

In order to address the current overdose crisis, we need to attend to how making available spaces of refuge, participation, and belonging facilitates the kinds of lives that allow a person to go everyday to a clinic to pick up their prescription heroin, or to an overdose prevention site, or to reduce the amount of drugs they use.

Put simply, to stem the current crisis, we need to address entrenched poverty in Vancouver’s inner city at the same time as we develop more and better biomedical and harm reduction interventions.

*

Danya Fast is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Medicine at the University of British Columbia. Since 2007, her ethnographic work in Canada and Tanzania has focused on how young people who inhabit the margins of urban space understand, experience, and imagine their “place” in the city.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply