Coming out as Métis

Former Downtown Eastside francophone cop makes good.

December 10th, 2016

Appearances can be deceiving. Gerry St. Germain played the game and won as a Conservative MP.

Indebted to Brian Mulroney and Stephen Harper, Gerry St. Germain owed much of his integrity as a Senator to his Métis roots.

REVIEW: I Am a Métis: The Story of Gerry St. Germain

by Peter O’Neil

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2016.

$32.95 / 978-1-55017-784-8

*

Jean Barman reviews Peter O’Neil’s I Am a Métis: The Story of Gerry St. Germain, a noteworthy account of Senator Gerry St. Germain’s journey from Grantown, Manitoba, to the Canadian Senate via the federal riding of Mission-Port Moody.

Along the way, St. Germain acknowledged his Métis identity and descent from the Metis leader of the North West Company faction at The Battle of Seven Oaks in 1816.

Almost four years ago I spent a snowy Ottawa winter’s evening jousting with Gerry St. Germain. I was an invited witness before the Senate’s Standing Committee on Aboriginal Peoples, then examining government policy towards Canada’s Métis people, and Gerry was a newly retired senator who had up until then chaired the committee.

I was persuaded to appear on the grounds that the Committee was about to complete its hearings and had found no one able to discuss the topic from a British Columbian perspective.

In the required background paper, I described the province’s considerable population identifying themselves as Métis by virtue of mixed Indigenous and non-Indigenous descent who did not fit the federal government’s narrower definition of Métis descent as having to originate in Manitoba or Saskatchewan. Gerry, British Columbian but born in Manitoba, was also invited, and so we appeared side by side.

I developed enormous respect for Gerry over the course of the evening. Questioned by his fellow committee members, we disagreed about most everything respecting who in British Columbia counted as Métis except the importance of the subject itself. We did so respectfully. Gerry listened and was genuinely curious, or so I inferred, concerning other perspectives to his own, about which I learned a lot. He was committed and passionate about who he was as a Métis person, and, while we differed on the boundaries of belonging, I admired him for being so.

The consequence is that I jumped at the opportunity to review Gerry St. Germain’s biography. Written in straightforward, accessible prose by respected national affairs journalist Peter O’Neil, I am a Métis takes its title from St. Germain’s assertion of identity in his final speech in Parliament as a retiring senator in October 2012. The biography tracks St. Germain’s pathway to that statement of self, whose aftermath I briefly glimpsed.

Gerry St. Germain was self-made. He became who he was by virtue of hard work and determination. Descended from nineteenth-century Manitoba Métis Cuthbert Grant of Scots and Cree descent, St. Germain was born in 1937 into very modest circumstance not far from Winnipeg in a small community originally called Grantown. Following a stint as a pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force, he was eight years a policeman, latterly in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, before settling his family in Port Coquitlam and going into business with increasing success.

By the early 1980s Gerry St. Germain was eying federal politics, where his knowledge of French from his childhood proved to be an important asset on meeting Brian Mulroney at a time he was seeking to wrest the leadership of the federal Progressive Conservative Party from Joe Clark. A 1983 by-election in Mission-Port Moody gave St. Germain the opening he sought, being assisted in winning the seat by a visit from now party leader Mulroney, who would win a federal seat at the same time.

The two French speakers would continue to be political allies and mutual supporters to the advantage of both of their political careers. Having won in the by-election and also in the general election in 1984, St. Germain could not hold onto his redrawn seat in 1988, due in part to Mulroney’s lessening appeal in the west. Here as elsewhere assisted by fulsome stories by many of the participants in events, including St. Germain, O’Neil chronicles his elected political career through a combination of vignettes and insider chronology.

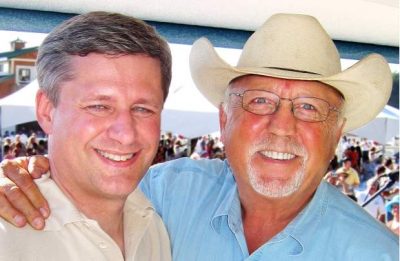

In 2006, PM Stephen Harper attended Senator Gerry St. Germain’s annual summer barbecue, and also attended his 50th anniversary party.

Gerry St. Germain was not done with federal politics. Looking to a comeback, with Mulroney’s support, he was acclaimed president of the federal Progressive Conservative party in 1989 at a time it was in fast decline. Assisted by access to St. Germain’s sometimes blunt diary, O’Neil provides a fascinating insider account of these tumultuous years when Preston Manning’s Reform Party was on the rise, to be followed by the accession of Stephen Harper.

In 1992 St. Germain’s political future revived when Mulroney, just as he was stepping down, in appreciation of “your loyalty and hard work for me and all of Canada” (147), appointed his fifty-five-year-old longtime ally to the Senate. This final act of the man who might be said to have made St. Germain’s federal career based on their common appreciation of the French language thereupon breathed new life into it.

It was during Gerry St. Germain’s two decades in the Senate that he turned attention to indigenous issues. Earlier he had dressed in a distinctive western fashion, but that was about all. As captured in a 1983 vignette, “the aficionado of everything Western — culture, history and especially fashion — was wearing a Stetson and a steel-blue Western cut suit” (8, 183). Indicative of changing attitudes more generally, St. Germain’s public claiming of his indigenous inheritance would be slower in coming. While St. Germain once referred in public to indigenous blood “coursing through my veins” (200), and identified himself as Métis in respect to attempts to have Métis leader Louis Riel’s treason conviction repealed, he did not use his background to political advantage or disadvantage. As explained by a close acquaintance from the 1980s:

He barely admitted that he had an aboriginal ancestry when he first entered politics. Pride in his Métis roots only began to emerge — and only as a mere acknowledgement — when he entered the cabinet in 1988. It was only after he became a senator that he started really talking deeply about his aboriginal background and his Métis lineage, and that he started being interested in the issues (207).

According to a trusted indigenous acquaintance, St. Germain came to value “what he was able to achieve as a Métis person.” (205).

On Harper’s accession to power in 2006, Gerry St. Germain was rewarded with the chairmanship of the Senate’s Standing Committee on Aboriginal Peoples, which gave him a platform on which to act. He used his position to put indigenous leaders in contact with politicians, as well as to effect policy shifts. Together with the committee’s former chair Nick Sibbeston, a Dene residential school survivor and former premier of the North West Territories who St. Germain made his vice chair, and along with the other committee members, he tramped indigenous Canada.

The result was over the next half dozen years a series of reports. Particularly influential were, according to O’Neil, the 2006 report on land claims which “was essentially adopted as government policy” (196); a 2007 report on safe drinking water; and a report, also of 2007, that suggested ways to stimulate economic activity. The last of the reports under St. Germain’s watch would become the one I witnessed on the sidelines, which was in essence his summation of who he was in a Canada in the making.

I am a Métis is well worth reading. It is appealing both as a biography and as an entryway to Canada’s — and British Columbia’s — political, indigenous, and human history over the past third of a century. There is a lot to learn.

*

Jean Barman’s books, co-edited volumes, articles, and book chapters on British Columbian, Canadian, and Indigenous history have won fifteen Canadian and American awards, most recently the Governor General’s Gold Medal for Scholarly Research. Her current book is Abenaki Daring: The Life and Writings of Noel Annance, 1792-1869 (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016), after whom Annacis Island in the Fraser River is named. She is professor emeritus at the University of British Columbia, a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, recipient of the George Woodcock Lifetime Achievement Award, and in 2016 the proud recipient of an Honorary Doctor of Letters from Vancouver Island University.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University.

—

BC BookWorld

ABCBookWorld

BCBookLook

BC BookAwards

The Literary Map of B.C.

The Ormsby Review

Leave a Reply