#93 HMS Pinafore on the Pacific

February 23rd, 2017

REVIEW: Britannia’s Navy on the West Coast of North America, 1812-1914

by Barry Gough

Victoria: Heritage House, 2016. $29.99 / 9781772031102

Reviewed by Howard Stewart

*

Fans will know that Barry Gough, British Columbia’s premier naval historian, is equally seadog and landlubber. His torrid pace in retirement has included major books on Juan de Fuca (2012), Peter Pond (2014), and Victoria High School in the Great War (2014).

Gough now gets his sea legs back with Britannia’s Navy on the West Coast of North America, 1812-1914, an account of the role of the Royal Navy in the early history of British Columbia.

Reviewer Howard Stewart notes that while the Royal Navy ensured the survival of a colonial British presence at a time of bellicose “manifest destiny” from the south, the same navy also engaged from time to time in gunboat diplomacy with the Indigenous inhabitants of the B.C. coast. — Ed.

*

This book is a revision, after forty-five years, of distinguished naval historian Barry Gough’s first major publication on naval history, The Royal Navy and the Northwest Coast of North America, 1810-1914: A Study of British Maritime Ascendancy (1971) — the first book published by UBC Press.

Gough’s key message is that the Royal Navy repeatedly provided much of the skill and power the British Empire required to conquer, and then hold, its most distant of colonial outposts here on the northeast Pacific shore.

Illustrious representatives of empire like James Cook and George Vancouver and their crews had already come and seen the place; others followed them to trade. Much is made, in traditional B.C. histories, of the roles of the maritime sea otter trade and the spreading terrestrial domain of the Hudson’s Bay Company in establishing a British foothold in this distant portal.

Gough doesn’t deny these roles; he simply aims to restore some balance to our perspective by pointing out how Britain’s remarkable globe-spanning navy also helped ensure the survival of a sometimes tenuous British presence, not just in those early years but throughout the nineteenth century.

To this end, Gough recounts the repeated critical interventions of the Royal Navy that helped this tiny, isolated, and vulnerable Eurasian enclave come into existence and then stay there. In the process, he recounts fascinating tales of geopolitics unfolding around the Pacific and, increasingly, around the Salish Sea.

One of the many strengths of the book is the rich detail Gough shares about the remarkable technologies mastered by this navy, especially in the age of sail and before the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914. It was a time when skilled mariners who had “mastered the passage” could expect to spend almost two months just making the run from Rio de Janeiro to Valparaiso; the return voyage was a little faster thanks to the powerful westerlies forever sweeping across the wild southern Pacific. And that’s only the middle section of the five or six month odyssey from England, via the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), to the Royal Navy’s base at Esquimalt on Vancouver’s Island.

Gough rightly points out that “the history of British Columbia is the history of transportation” (p. 18). Canadian grandees, from John A. Macdonald to W.A.C. Bennett, would certainly agree with him. This author’s great contribution is to remind us of the naval dimension of this history of transportation: the decisive early role played by the Royal Navy’s mastery of navigation and its sheer power on the global oceans.

He also shows us the many influences of that navy’s evolving relationship with other “blue water” navies, most notably that of the US, but also of the Russian and Japanese empires; all were active, but some were far more threatening than others.

While the Japanese were increasingly reliable allies, the Russians were a constant threat on the northeast Pacific, and their risk was increased by their often cozy relations with the bulimic republican American empire spreading so rapidly across the middle of North America.

The danger posed by Moscow’s Pacific fleet was a distant but very real echo of the “Great Game” the two empires were locked in across Asia. It flared up in times of conflict such as the Crimean War in the 1850s, when British admirals fretted about possible aggression by the Russian navy against their Vancouver Island haven at Esquimalt, which they started using as a north Pacific station in 1848, and where a graving dock was built in 1887.

This kind of global geopolitical worry in London contrasted with the frequent diffidence displayed by imperial governments when responding to more local tempests around the same time, such as those arising in the San Juan Islands, or even in B.C.’s flash-in-the-pan gold rush on the Fraser River.

Yet the need to resist repeated American urges to fulfill their “manifest destiny” was a compelling imperative through most of the century. The victory of federalist forces south of the border in 1865 unleashed a wave of mostly unjustified paranoia in British North America about Fenian terrorists aiming to destabilize and even conquer British colonies and possessions, including the two colonies north of the new US Territory of Washington.

The American purchase of Alaska, engineered by Secretary of State William Seward two years after the end of their civil war, was undoubtedly a more real threat. The Americans’ good relations with the Russian Empire bearing down from the north had been worrisome enough; now Seward boasted that his purchase of Alaska would render “the permanent political separation of British Columbia from Alaska and Washington territory impossible” (p. 265).

As the century reached its final years, Britannia’s navy increasingly came up against the realization that it would have to share its rule of the waves with others, particularly as the newly united German Empire began its own concerted effort to challenge British domination of the seas.

Out here on the far side of the world such challenges helped stimulate accommodation instead of competition with the rambunctious southern neighbours. The US was now steadily building up its own powerful naval presence on the Pacific in general, and across the Strait of Juan de Fuca and along Puget Sound in particular.

The growing disparity by the end of the century led Rear Admiral A.K. Bickford, the Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Navy in the Pacific, to complain of the urgent need to recognise the “dangerously weak state” of his forces. The reply from Britain’s First Lord of the Navy was not encouraging: “The very fact of the great superiority of the US Squadron in the Pacific should shew us how impossible it is for us in view of the requirements elsewhere to maintain a Squadron in the Pacific capable of coping with it. It is impossible for this country in view of the greater development of foreign navies to be a superior force everywhere” (p. 297).

Some readers will take issue with Gough’s chapter on the role of the Royal Navy in consolidating imperial control over this coast’s Indigenous people.[1] While recognizing the legacy of distrust and pain left by First Nations mistreatment at the hands of Royal Navy gunboats and drunken sailors, the author sometimes seems to accept the imperial rhetoric of the time a little too uncritically.

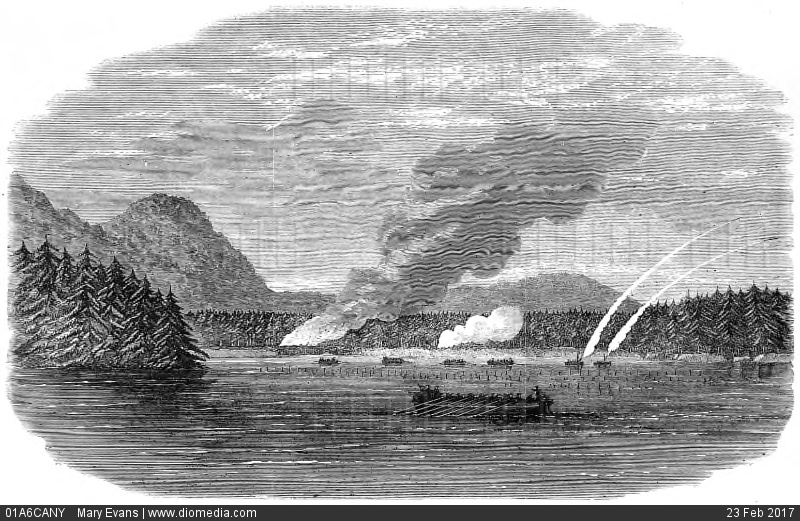

The boats of HMS ‘Sutlej’ and HMS ‘Devastation’ are depicted attacking a Nuuchahnulth (Nootka) village in Clayoquot Sound, Vancouver Island, 1864. The British boats attacked the Indian village in retaliation.

The files that Gough has mined so ably in Britannia’s Navy were those of an imperial power with little or no concern about the long-term effects on local Indigenous populations of their standard techniques of imperial control. Razing the odd village was just something that had to be done to keep the Natives in check.

Gough is also somewhat too accepting of official British explanations about their strategies on the larger geopolitical stage. It’s one thing to point out that pragmatic imperial thinkers “never had a grand design in their expansionist tendencies… [and] had no theory of imperialism or of empire… [and wanted only] peace for the purpose of profit…,” but it’s another to suggest that “they fought for stable government… and stable places for their investments (p. 16).”

In fact, as the Opium Wars and many smaller interventions around the world demonstrated, the British Empire often sought to destabilize or simply eradicate competent governments that stood in the way of Imperial commercial and investment plans.

But these are tangential quibbles, from a twenty-first century perspective, about Gough’s main contribution: a masterfully researched naval history assembled, originally, in the second half of the twentieth century and drawing upon a rich trove of archival material from the nineteenth century.

And while Gough has not provided a twenty-first century sort of history sounding the views of many different types of actors, he has written a very entertaining one that brings alive the remarkable history of the Royal Navy on the northeast Pacific and charts its very substantial contributions to the survival of the tiny and improbable British outpost that emerged here over the nineteenth century.

*

Howard Macdonald Stewart is an historical geographer and non-practicing international consultant who writes from Denman Island where he has lived, off and on, for more than thirty years. He has worked in more than seventy countries since the 1970s and is now intensely allergic to airplanes. He reviewed many books for BC Studies and is now reviewing for The Ormsby Review. His 17,000-word story of a bicycle trip down the Danube with Cornelius Burke in 1973 was published as The Ormsby Review’s popular #21 (September 28, 2016). His forthcoming book on five parallel histories of the Strait of Georgia / North Salish Sea, based on his doctoral research in the Geography Department at UBC, is scheduled for publication by Harbour in 2017. An insider’s view of his four decades on the road, notionally titled Around the World on Someone Else’s Dime: Confessions of an International Worker, is also a work in progress.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

—

BC BookWorld

ABCBookWorld

BCBookLook

BC BookAwards

The Literary Map of B.C.

The Ormsby Review

[1] See See Chris Arnett, The Terror of the Coast: Land Alienation and Colonial War on Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands, 1849-1863 (Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1999).

Leave a Reply