#90 James Teit

January 28th, 2016

LOCATION: A Heritage Branch plaque can be found near the Chief Tetlenitsa Memorial Outdoor Theatre near the junction of the Nicola and Thompson Rivers at the Five Nations Campground, slightly northeast of Spences Bridge, on the Trans Canada Highway. It commemorates the life of one of the most remarkable British Columbians most people have never heard of–James Teit.

When the anthropologist Franz Boas met James Teit in the summer of 1894, he hired him immediately. “The young man, James Teit, is a treasure!” he wrote. Educated in Scotland until only age 16, Teit became fluent in several First Nations languages. In addition, he spoke some German, Dutch, French and Spanish. This fluency enabled Teit to become the first literate activist for aboriginal rights in B.C.

QUICK ENTRY:

The chiefs of British Columbia referred to James Teit as their “hand.” When Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier visited Kamloops in 1910, it was James Teit who prepared the official response on behalf of the Secwepemc, Okanagan and Nlaka’pamux nations, delivered by Chief Louis of Kamloops, to assert rights to their traditional lands. Teit also accompanied the delegation of 96 chiefs from 60 B.C. bands who met with Premier Richard McBride and his cabinet in Victoria in 1911. In 1912, he went to Ottawa with nine chiefs to meet with newly elected Conservative Prime Minister Robert Borden, during which time Teit translated the four speeches made by John Chilahitsa (Okanagan), Basil David (Secwepemc), John Tedlenitsa (Nlaka’pamux) and James Raitasket (Sta’atl’imx). Teit delivered a statement to Borden for the delegation: “We find ourselves practically landless, and that in our own country, through no fault of ours, we have reached a critical point, and, unless justice comes to the rescue, we must go back and sink out of sight as a race.” He returned to Ottawa with eight chiefs in 1916.

When the 1912–1916 Royal Commission issued its report on aboriginal grievances, the Allied Tribes opposed it, and again it was James Teit who replied on their behalf, “The Indians see nothing of value to them in the work of the Royal Commission. Their crying needs have not been met.” In 1917, Teit and Reverend Peter Kelly sent a telegram to Borden to oppose conscription for aboriginal men, likening it to enslavement, because the land question remained unresolved and aboriginals were being denied their basic rights as citizens. At Teit’s urging, an order-in-council was passed on January 17, 1918, to exempt aboriginals from conscription. Teit and Kelly also published a 6,000-word pamphlet to formally reject the McKenna-McBride report on behalf of the Allied Indian Tribes of British Columbia, an organization Teit co-founded. In 1920, he circulated a document in Ottawa to members of parliament entitled A Half-Century of Injustice toward the Indians of British Columbia.

A self-taught botanist, Teit also worked as an entomologist, a photographer and an anthropologist who published 2,200 pages of ethnological material and also produced almost 5,000 pages of unpublished manuscript material (according to University of Victoria historian Wendy Wickwire in the Canadian Historical Review, Vol. 79, No. 2, 1998). His first of eleven significant anthropological publications was Traditions of the Thompson River Indians of British Columbia (1898). The owner of a wax cylinder recording machine, Teit also recorded local singers and identified them with catalogued photographs.

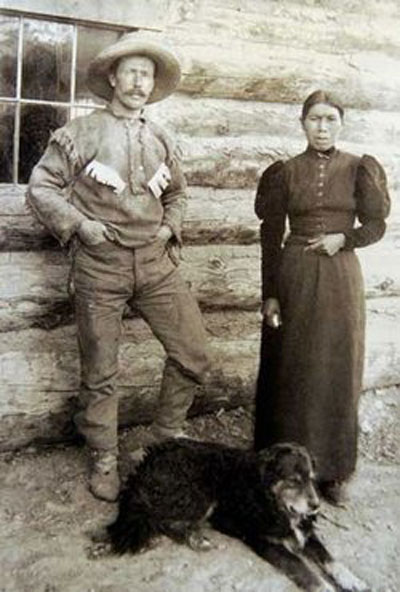

Born on the Shetland Islands, Scotland, in 1864, Teit immigrated to Spences Bridge in the Fraser Canyon in 1884 to help manage a store on the estate owned by his uncle, John Murray, at which time Teit reverted to the Norse spelling of his surname, Tate. He married a member of the Nlaka’pamux nation, Susanna Lucy Antko, with whom he lived happily for twelve years until her death in 1899. After Teit remarried in 1904, his six children received Scandinavian names. It is seldom noted that Teit became a member of the Socialist Party of Canada, reading socialist books by American and German authors as early as 1902. James Teit died in 1922, in Merritt.

“Unlike [Franz] Boas,” Wickwire writes, “who viewed Native peoples as remnants of the past—academic subjects of study or anthropological ‘informants’ through whom he could reconstruct an image of the pre-contact past—Teit viewed Native peoples as his contemporaries—friends, relatives, and neighbours who lived a lifestyle similar to his own.”

FULL ENTRY:

“His myriad connections… to British Columbia’s Aboriginal communities are unparalleled in the history of the province.” – Judy Thompson

James Teit was not an Aboriginal, but he was the first highly literate, ongoing activist for Aboriginal rights in British Columbia, serving as a translator, scribe and lobbyist. The chiefs of British Columbia referred to him as their “hand.” He helped them co-found the Allied Indian Tribes of British Columbia in 1916, having previously helped form the Interior Tribes of British Columbia (ITBC) and the British Columbia Indian Rights Association in 1909. Known primarily as one of the main informants and guides for anthropologist Franz Boas, Teit published 2200 pages of ethnological material in forty-three sources and also produced almost 5,000 pages of unpublished manuscript material (according to UVic historian Wendy Wickwire in the Canadian Historical Review, Vol. 79, No. 2, 1998).

It is seldom noted that Teit became a member of the Socialist Party of Canada, reading Socialist books by American and German authors as early as 1902. He subscribed to the socialist newspaper in Vancouver and occasionally made donations to the Western Clarion. In 1902 he wrote to a Shetland Islander, “Now I understand better what socialism is and what good news it has for people.” That same year he stated his views publically in the Canadian Socialist, “I am in favour of socialism and wish to understand its aims better. It is gaining ground here and if a socialist is run in the Yale-Kootenay district next election I think he is sure to go in.” British Columbia had already elected a socialist representative to its Legislative Assembly and Montana to the south had elected 18 socialists.

It is seldom noted that Teit became a member of the Socialist Party of Canada, reading Socialist books by American and German authors as early as 1902. He subscribed to the socialist newspaper in Vancouver and occasionally made donations to the Western Clarion. In 1902 he wrote to a Shetland Islander, “Now I understand better what socialism is and what good news it has for people.” That same year he stated his views publically in the Canadian Socialist, “I am in favour of socialism and wish to understand its aims better. It is gaining ground here and if a socialist is run in the Yale-Kootenay district next election I think he is sure to go in.” British Columbia had already elected a socialist representative to its Legislative Assembly and Montana to the south had elected 18 socialists.

Born on the Shetland Islands, Scotland in 1864, to parents John and Elizabeth (Murray) Tait, James Teit emigrated from Scotland at age 19. He immigrated to Spences Bridge in the Fraser Canyon in 1884 to help manage a store on the estate owned by his uncle, John Murray. It was at this time that Teit decided to change his name, something he’d long asked his father to do. “Jamie, you have been after me for some time to change the spelling of our name back to the old Norse spelling of ‘Teit’,” said James’ father. “It was not practical for me to do this, having been in business for years under the present name. You are going to a new country, to start a new life. Now is the time to change your name, if you still wish.”

He married a Thompson (Nlaka’pamux) Indian, Susanna Lucy Antko, aged 25, on September 12, 1892, in a ceremony at Spences Bridge, officiated by Reverend Richard Small, but she died childless on March 2, 1899. They had lived happily together for 12 years. The cause of her death has been cited has either pneumonia or tuberculosis. Her marked grave can be found in Spences Bridge.

In 1904, Teit remarried Leonie Josephine Morens or Josie as she was called, the daughter of Pierre and Franchette Morens. The couple visited Nanaimo, B.C. for their honeymoon. Because of her French background, Teit’s wife often called him Jacques, although she also referred to him as Mr. Teit. They had six children: Eric (1905-77), Inga (1907-93), Magnus (1909-82), Rolf (1912), who died at birth, Sigured (1915-?), and Thorald (1919-82). “Father was born in the Shetland Islands, which, as you know, is peopled to a large degree by Scandinavians, said Inga Teit Perkin in an interview with the Nicola Valley Historical Quarterly. “He was of Scandinavian descent and for this reason, all us children were given Scandinavian names.”

Franz Boas first met Teit in the summer of 1894 while employed in field research for the Committee of the British Association for the Advancement of Science for the Study of Northwestern Tribes, overseen in Canada by Horatio Hale (“the father of Northwest anthropology,” according to Douglas Cole) who had hired Boas in the summer of 1888. Boas recalled in his journal, “I left the train at Spences Bridge, which is a little dump of three or four houses and a hotel near the station…I went to see a man, a Salvation Army Warrior and big farmer…supposed to know the Indians very well. He sent me to another young man, who lives three miles up the mountain and who is married to an Indian…. He knows a great deal about the tribes. I engaged him right away.”

Despite no formal education beyond the age of sixteen in Lerwick, on the Shetland Islands, Teit became fluent in several tribal languages, plus he spoke some German, Dutch, French and Spanish. A self-taught botanist, he also became an entomologist, a photographer of plants and people, and an anthropologist, receiving first-hand training from Boas during the summer of 1897. During this period they recorded songs and conducted interviews in the Spences Bridge region. Teit also accompanied Boas on a five-week trip from Spences Bridge to Bella Coola. He completed his first major publication, Traditions of the Thompson River Indians, in 1898, followed by The Thompson Indians of British Columbia two years later. Teit’s first writings were published by the British Association for the Advancement of Sciences as part of their paper, The North Western Tribes of Canada, in the Report of their 65th Meeting.

Between 1911 and 1918, Teit worked for the Geological Survey of Canada, then afterwards as a rancher and prospector. As the owner of a wax cylinder recording machine, Teit recorded local singers and identified them with catalogued photographs. “Unlike Boas,” according to Wendy Wickwire, “who viewed Native peoples as remnants of the past — academic subjects of study or anthropological ‘informants’ through whom he could reconstruct an image of the pre-contact past — Teit viewed Native peoples as his contemporaries — friends, relatives, and neighbours who lived a lifestyle similar to his own.”

Because of his fluency in tribal languages, Teit often acted as an intermediary between the First Nations and white officials. When Sir Wilfrid Laurier visited Kamloops in 1910, it was James Teit who prepared the official response on behalf of the Shuswap, Okanagan and Thompson tribes, delivered by Chief Louis of Kamloops, to diplomatically assert rights to their traditional lands. “We welcome you here, and we are glad we have met you in our country. We want you to be interested in us, and to understand more fully the conditions under which we live. When the seme7uw’i, the Whites, first came among us there were only Indians here. They found the people of each tribe supreme in their own territory, and having tribal boundaries known and recognized by all. The country of each tribe was just the same as a very large farm or ranch (belonging to all the people of the tribe)…. They [government officials sent by James Douglas] said that a very large reservation would be staked off for us (southern Interior tribes) and the tribal lands outside this reservation the government would buy from us for white settlement. They let us think this would be done soon, and meanwhile, until this reserve was set apart, and our lands settled for, they assured us that we would have perfect freedom of travelling and camping and the same liberties as from time immemorial to hunt, fish and gather our food supplies wherever we desired; also that all trails, land, water, timber, etc., would be as free of access to us as formerly. Our Chiefs were agreeable to these propositions, so we waited for treaties to be made, and everything settled.”

It is tempting to suggest that effective Aboriginal political dissent within British Columbia arose with the appearance of James Teit, but in fact more than 100 Aboriginal leaders in the Fraser Valley had signed a petition in 1874 to protest the arbitrary division of their land and resources. Later in that same decade Father C.J. Grandidier, an Oblate priest, articulated similar complaints on behalf of Kamloops Indians in the Victoria Standard newspaper. In 1904, escorted by Father J.M. Lejeune, Chiefs Chilahitsa of Douglas Lake and Louis of Kamloops travelled to England hoping to gain an audience with King Edward VII. When this gambit proved unsuccessful, they continued to Rome where they gained a hearing with Pope Leo XIII. No doubt this audience with the Pontiff influenced the plans of Squamish Chief Joe Capilano in 1906 when he travelled to London in 1906 and gained a sympathetic audience with King Edward VII, along with Cowichan chief Charley Isipaymilt and Shuswap Chief Basil David of the Bonaparte Band. Upon Capilano’s return, a petition signed by sixteen chiefs from around the province was presented to Canadian authorities to assert that “the Indian title” to their lands had never been formally extinguished, as was the case in most other regions of Canada. Chief Joe Capilano convened an organizational meeting of Aboriginal leaders in December of 1907, giving rise to a delegation of twenty-five chiefs to Ottawa in 1908.

In July of 1908, Teit also became directly involved, writing the text for a four-page petition entitled “Prayer of Indian Chiefs”, signed in Spences Bridge and sent to the superintendent general of Indian affairs, A.W. Vowell. This document demanded better schools, resident doctors and compensation for railway rights of way. “Our country has been appropriated by the whites without treaty or payment … In comparison with our fellow Indians of Alberta, Eastern Washington and Idaho, we have been simply neglected to speak mildly and we feel this strongly.” In 1910 Teit spent much of time visiting reserves for Indian rallies on behalf of the Indian Rights Association (IRA). This liaison work was demanding and not entirely welcome. He later wrote, “I simply could not get out of this work. I was so well known to the Interior tribes and had so much of their confidence, and was so well acquainted with their customs, languages and their condition and necessities they kept pressing me to help them and finally dragged me into it.” Teit’s efforts to unite the activities of the IRA and ITBC left him precious little time for anthropological work.

In February of 1910, James Teit wrote to Franz Boas, “… I have been busy traveling around, and speaking to the Inbians so as to get them united in an effort to fight the BC Government in the Courts over the question of their lands. Owing to the stringency in the laws, increased settlement in the country, and general development of the Capitalist system, the Indians are being crushed, and made poor, and more & more restricted to their small, and inadequate reservations. The BC Government has appropriated all the lands of the country, and claims also to be sole protector of the Ind. Reserves. They refuse to acknowledge the Ind. title, and have taken possession of all without treaty with or consent of the Indians. Having taken the lands they claim complete ownership of everything in connection therewith such as water, timber, fish, game, etc. They also subject the Indians completely to all the laws of BC without having made any agreement with them to that effect. The Indians demand that treaties be made with them regarding everything the same as has been made with the Indians of all the other provinces of Canada and in the US, that their reservations be enlarged so they have a chance to make a living as easily and as sufficient as among the Whites, and that all the lands not required by them and which they do not wish to retain for purposes of cultivation and grazing, and which are presently appropriated by the BC Government be paid for in cash. The Indians are all uniting and putting up money and have engaged lawyers in Toronto to fight for them, and have the case tried before the Privy Council in England.”

James Teit prepared the documents that were presented to Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier upon his visit to Kamloops in August of 1910. He also accompanied the delegation of ninety-six chief from sixty B.C. bands to meet with Premier Richard McBride and his cabinet in Victoria on March 3, 1911. In January of 1912, Teit travelled to Ottawa with nine chiefs to meet with newly elected Conservative Prime Minister Robert Borden, during which time Teit translated the four speeches made by John Chilahitsa (Okanagan), Basil David (Secwepemc), John Tedlenitsa (Nlaka’pamux) and James Raitasket (Sta’atl’imx). Teit delivered his own statement to Borden and presented his delegation’s written plea, “We find ourselves practically landless, and that in our own country, through no fault of ours. We have reached a critical point, and, unless justice comes to the rescue, we must go back and sink out of sight as a race.”

Neither justice or the cabinet of Robert Borden came to the rescue. Two months later Borden had failed to respond to the written entreaty, so the original delegation, augmented by sixty additional chiefs, waylaid Prime Minister Borden in Kamloops on March 15, 1912 in order to reiterate their requests. Borden felt obliged to appoint a special commissioner of Indian affairs, J.A.J. McKenna, to adopt a sensible agreement with the BC government. Premier McBride and McKenna signed an accord to hold public hearings on B.C. reserves throughout the province. But forty-eight chiefs reluctantly convened in Spences Bridge on May 23, 1913 in order to reject the McKenna-McBride Royal Commission on Indian Affairs for the Province of British Columbia because it lacked Aboriginal representation and because it was not addressing the issue of title for their lands. By 1915 Teit was obliged spent a week preparing a letter signed by thirty-eight chiefs after the federal cabinet passed an Order-in-Council (PC 751) that would require the Aboriginal leaders to accept the McKenna-McBride Commission’s Report in advance of is publication. Teit drafted the commonsensical response: “We consider it unreasonable that we should be asked to agree to the findings of the Royal Commission when we have no idea what their findings will be or whether the same will be satisfactory to us. We cannot agree to a thing that we know nothing about.”

Once more Teit traveled to Ottawa, this time with eight ITBC chiefs, in May of 1916, in an attempt to influence Borden directly, but it was clear the Royal Commission was never intended to appease Aboriginal interests. Upon his return to Vancouver, Teit attended the three-day meeting of Aboriginal leaders in June that succeeded in uniting the ITBC and IRA to produce a larger umbrella organization, the Allied Tribes of British Columbia (ATBC), to represent all factions opposed to the government’s unwillingness to compromise with regards to its Royal Commission. A four-man executive committee for the new ATBC was duly elected, consisting of the Methodist minister Peter Kelly, John Chilahitsa, Reverend Arthur O’Meara, Basil David and James Teit.

When the 1912-1916 Royal Commission issued its report on Aboriginal grievances, the Allied Tribes opposed it, and again it was James Teit who replied on their collective behalf, “The Indians see nothing of value to them in the work of the Royal Commission. Their crying needs have not been met. The commissioners did not fix up their hunting rights, fishing rights, water (for irrigation) rights, and land rights, nor did they deal with the matter of Reserves in a satisfactory manner. Their dealing with Reserves has been a kind of manipulation to suit the whites, and not the Indians. All they have done is to recommend that about forty-seven thousand acres of, generally speaking, good lands be taken from the Indians and eighty thousand acres of, generally speaking, poor lands be given in their place. A lot of the land recommended to be taken from the Reserves has been coveted by whites for a number of years.”

With the election of a new Liberal government in Victoria in September of 1916 and the rising importance of World War One, little effort was made to implement the recommendations of the Royal Commission. But Teit and Peter Kelly were forced into action one year later when Borden’s federal government imposed conscription in October of 1917. In accordance with the introduction of a new Military Service Act, all bachelors and widowers were required to report for military duty if they were between the ages of twenty-four and thirty-four. Teit and Kelly sent a telegram to Prime Minister Borden to oppose conscription for Aboriginal men, likening it enslavement, because the land question remained unresolved and Aboriginals were being denied their basic rights as citizens. At Teit’s urging, an order-in-council was passed on January 17, 1918 to exempt Aboriginals from conscription. Undoubtedly Teit’s activism on this issue was influenced by his socialist beliefs. He privately wrote, “The War probably (under present economic and social conditions) had to come and advancement will probably come out of it and good in the end, but at the same time it is a disgrace for people calling themselves Christian and Civilized. All these nations … claim to be fighting for democracy. This is quite ridiculous. Who ever heard of any modern capitalist class fighting for democracy?”

By war’s end, Teit and Kelly reconvened and published a 6,000-word pamphlet entitled Statement of the Allied Indian Tribes of British Columbia for the Government of British Columbia in order to formally reject the McKenna-McBride report on behalf of the ATBC. Arthur Meighen, the federal Indian affairs minister, nonetheless introduced Bill 13 to implement the controversial Commission Report. Teit, O’Meara and four chiefs once more made the journey to Ottawa, circulating a document to members of parliament entitled A Half-Century of Injustice toward the Indians of British Columbia, but to no avail. The bill passed its third reading on April 13, 1920. The Allied Tribes were insufficiently organized to muster further protests after the federal Parliament stubbornly went ahead with its recommendations. More sympathetic when he took office, William Lyon Mackenzie King sent his Minister of the Interior, Charles Stewart, to Vancouver in 1922. But by then Teit’s health was failing.

After a lengthy illness caused by a bladder infection, James Teit died on October 30, 1922, at age 58, in Merritt. If James Teit had not died in 1922, it’s possible the story of Aboriginal relations with B.C. government would have turned out differently. As Peter Kelly recalled in a 1953 interview with James Teit’s son Sigurd, “The organization of the Interior Indians fell apart after Teit’s death. Not altogether, but it was never the same again.”

James Teit’s house, now a privately owned Arts and Crafts bungalow, remains in Spences Bridge, on the north side of the river, alongside Teit’s workshop. About 3 kilometres north of the village is The Hilltop Farm location where Teit’s in-laws lived in an house he owned (still standing in 2015), As well, Teit and second wife, Josie Morens, lived there with the Morens parents until they moved into Teit’s bungalow in the village. Teit also had a ranch above the Morens ranch (in the Twaal Valley). There is a family cemetery behind the Morens house that includes Teit’s relatives and some of his children. By far the best commemorative display for and about James Teit can be seen at the Merritt Museum. Teit’s gravestone can be found at the Pine Ridge Cemetery in Merritt at 1675 Juniper Drive.

BOOKS:

Traditions of the Thompson River Indians of British Columbia, collected and annotated by James Teit, with an introduction by Franz Boas (Houghton Mifflin, 1898).

Teit, James. The Thompson Indians (Memoir No. 2 New York: American Museum of Natural History, 1900)

Teit, James. The Lillooet Indians (Memoir No. 4, Part 5 New York: American Museum of Natural History, 1906).

Teit, James. The Shuswap (Memoir No. 4, Part 7 New York: American Museum of Natural History, 1909).

Teit, James. Mythology of the Thompson Indians (American Museum of Natural History, 1912)

Teit, James et al. Coiled Basketry in British Columbia and Surrounding Region (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1928) [Co-authors H.K., Haeberlin and Helen H. Roberts; edited by Franz Boas].

Boas, Franz & James Teit. The Salishan Tribes of the Western Plateau (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1930).

Teit, James. Mythology of the Thompson Indians (New York: AMS Press, 1975).

Teit, James. Notes On the Early History of the Nicola Valley (pamphlet). Volkerkundliche Arbeitsgemeinschaft, 1979.

Teit, James & Franz Boas. Coeur D’Alene, Flathead and Okanogan Indians (Fairfield, Washington: Ye Galleon Press, 1985).

Teit, James. The Thompson Indians of British Columbia (Nicola Valley Museum & Archives Association, 1997). 0-920-755-02-X.

ALSO:

Thompson, Judy. Recording Their History: James Teit and the Tahltan (Douglas & McIntyre, 2007). 978-1-55365-232-8

[Alan Twigg / BCBW 2015]

Honouring the past (FROM THE MERRITT HERALD, JUNE 2010)

Pride, inspiration, honor, and heartwarming are some of the words that can express the feeling of guests at the First Annual Moqw Moqwx? es peye? Wixt (Coming Together as One) Gathering held in Spences Bridge.

Hosted by the Cooks Ferry Indian Band (Nlaka’pamux Nation) the Gathering is designed to celebrate and honor the work done 100 years ago by the Shuswap, Okanagan, and Nlaka’pamux Tribes assisted by noted ethnographer James Teit in developing the Sir Wilfred Laurier Memorial document. Between the years 1920 and 1922 Spences Bridge was the centre of meetings of Indian Leaders concerned with how their rights to land were being ignored by the federal and provincial governments. The gathering was also the grand opening of the Chief Tetlenitsa Memorial Outdoor Theatre.

Chief David Walkem welcomed all in attendance to Nkemcin, the mouth of the Nicola River on behalf of the Cooks Ferry community. Chief Walkem wore a traditional Nlaka’pamux headdress and buckskin shirt designed by Councillor Pearl Hewitt who as well wore traditional dress of buckskin and woven silver willow cape and hat. Master of ceremonies Raymond Phillips welcomed all in Nlaka’pamuxcin and introduced the three traditional Stickmen Ira Tom (Okanagan), Dennis Saddleman (Nlaka’pamux) and John Jules (Secwepemc). The Stickmen carried a staff with an eagle feather and their role was to uphold protocol in a respectful manner while keeping the event going.

The Chief Tetlenitsa Memorial Outdoor Theatre structure, with its architectural beauty in the concept of a traditional pit house and open concept staging and seating leaves the mind open to creativity, which is fitting since it was named after Chief Tetlenitsa from the Cooks Ferry Band.

Chief Tetlenitsa, an original signatory, of the Sir Wilfred Memorial was passionate about seeking a just resolution to the land question and also was well respected as an orator, teacher and singer. The ribbon cutting was actually the cutting of a buckskin strand held up by two eager Cooks Ferry Band youth Jada Raphael and Cole Mckay and the cutting being done by Cooks Ferry Band elders Doreen Albert and Don Ursaki.

The next part of the program was the rededication of the Sir Wilfred Laurier Memorial originally developed at a meeting in Spences Bridge in may 1910 and presented to the Prime Minister on August 25, 1910 in Kamloops.

Dr Ron Ignace from Skeetchstn provided historical context on the Memorial and how it related to traditional stories. Noted academic expert Dr Wendy Wickwire from the University of Victoria, provided a short history of the work that the Interior Allied Tribes did in Spences Bridge and how James Teit was able to assist them in their work.

A highlight of the day was the performance of an original play by Kevin Loring (Lytton First Nation) a governor General Award recipient for Drama in 2009, commissioned to mark the occasion. The performance by Kevin Loring, Ron Harris, Kim Harvey, and Sam Bob was full of every emotion a and educational for all and utilized the actual words of the original 1910 Sir Wilfred Laurier Memorial and brought them to life.

Chiefs and representatives of the original three signatory tribes were then asked to come forward and sign the following: “We the undersigned Chiefs and designated Representatives of the following Secwepemc, Sylix, and Nlaka’pamux Indigenous Nations gather together 100 years later to honor our ancestors efforts to find a just and lasting resolution to the land question and to rededicate our efforts to uphold and carry on the spirit and intent of the original Memorial this 11th day of June, 2010?.

In addition 22 Chiefs and representatives of the Taltan, Tsihl’qotin, St’atl’imc, Carrier, and Gitanmaax Nations in attendance signed to show their solidarity. An additional 218 Inigenous and Canadian citizens signed in solidarity with the leadership, including two guests from Australia, and one from the USA. Those signing used an eagle feather pen with beading done by Tricia Spence from Nicomen that read “1910 – 2010.”

At the end of the ceremonies Chief Walkem with help from Chief Kowaintco Michel and Cooks Ferry youth presented each invited Nation with an eagle feather and a vest designed by Nlaka’pamux designer Shannon Kilroy with logo done by Nadine Spence (Nlaka’pamux). After the ceremonies a feast was held at the Chief Whistemnitsa Community Complex, named after another original signatory from the Cooks Ferry community. The open mike at the feast was a great place for stories and thanks for the day.

The Chief and council of the Cooks Ferry Band wishes to thank Nadine Spence for coordinating the event and all the volunteers who helped make the day a success.

The gathering will be an annual event with each year devoted to the tremendous amount of work done by our ancestors in striving for a just and lasting resolution of the land question in B.C.

Leave a Reply