#87 Carol Shields

January 28th, 2016

LOCATION: 990 Terrace Avenue, Victoria

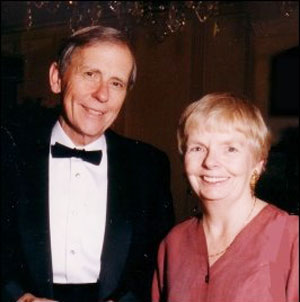

Carol Shields lived at this address for the final three years of her life, 2000-2003, with her husband Donald Shields. By that time she was widely acknowledged as one of Canada’s finest writers. As Alice Munro wrote, “You get a shiver when you come across a real writer and I had that with her.”

ENTRY:

It was a McGraw-Hill Ryerson editor named Julie Beddoes who picked out the manuscript for Small Ceremonies from the slush pile. After this first novel won the 1976 Canadian Authors Association Award for Fiction, Carol Shields went on to become one of Canada’s most celebrated writers, creating a body of work that upended notions of the ordinary and revealed truths about women’s lives, marriage, work, goodness and loss. Shields had already published two poetry collections before writing Small Ceremonies.

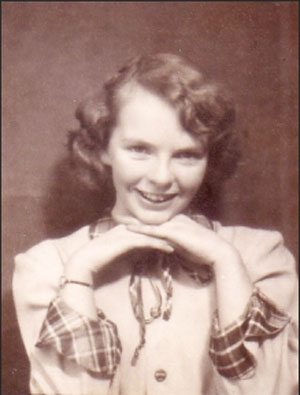

Carol Ann (Warner) Shields was born on June 2, 1935, the youngest of three children –twins had been born two years before her. She grew up in Oak Park, Illinois, a quiet suburb near Chicago. The daughter of a candy factory manager and a schoolteacher, she read a book a day.

After three years at Presbyterian Hanover College in Indiana, she attended the University of Exeter as an exchange student in 1955, and on a student trip to Aberfoyle, Scotland, met Donald Hugh Shields, a Canadian civil engineer. On one of their first dates, he took her to see the Pitlochry Dam. “He always made me laugh,” she said. “I knew at once it would be all right.”

The couple married two years later and Shields, 22, moved to Canada, becoming a naturalized Canadian in 1971. The young couple lived in Vancouver and Toronto. The first two of their five children were born in 1958 and 1959.

They lived in Manchester, England from 1960 to 1963, where Don Shields did post-doctoral studies. While there, Shields began reading the poetry of Philip Larkin and she sold several plays and her first short story to the British magazine The Storyteller. The couple’s third child was born in Manchester. Back in Toronto, Shields continued to write poetry and won the CBC’s Young Writers Competition in 1965. A fourth child was born in Toronto and a fifth completed the family in 1968 as the family transitioned to Ottawa.

Carol Shields’ first book of poetry, Others (1972), was followed by Intersect (1974). At the University of Ottawa she received her M.A. in English in 1975 for her thesis on the Victorian settler writer Susanna Moodie. This speculative thesis was the genesis of her first novel, Small Ceremonies. From 1980 to 2000, the Shields lived in Winnipeg; these were among the most productive years of Shields’ writing career.

Happenstance (1980) was followed by A Fairly Conventional Woman (1982). These provide the separate viewpoints of a husband and wife who are spending their first week apart after twenty years of marriage. The two novels were later published back to back in one volume as Happenstance: Her Story and His Story.

Swann (1987), is the story of four individuals who become enmeshed in the life and work of Mary Swann, a rural Canadian poet murdered by her husband. The Republic of Love (1992), presents Winnipeg as a quasi-magical city of romance.

Shields’ best known work, The Stone Diaries (1993), which won the Pulitzer among other prizes, is about Daisy Goodwill, who Shields described as “a middle-class woman, a woman of moderate intelligence and medium-sized ego and average good luck” who is tragically unknown to herself and to others. This novel reflects Shields’ own gradual appreciation of the women’s movement. “I’ve been witness to this huge change for women in the second half of the 20th century,” she said, having been awakened to feminism specifically by Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, a book that she says hit her “like a thunderbolt”.

“I came to feminism late,” she once told National Public Radio’s Terry Gross in the U.S. “I knew there was something wrong, I just didn’t know what it was. I was astonished. I had no idea women thought like that or women could be anything other than what they were…. It did change the way that I thought about myself. I did begin to do a graduate degree part-time, thought about doing some writing. It gave me courage.”

Another widely acclaimed novel, Larry’s Party (1997), is a sympathetic portrayal of Daisy Goodwill’s equivalent–an ordinary man. “Men are portrayed as buffoons these days,” Shields said. “I was trying not to do that. But men are the ultimate mystery to me. I wanted to talk about this business of men in the world.” Her protagonist designs garden mazes for a living. Larry’s Party was awarded the Orange Prize and shortlisted for the Giller Prize.

Shields’ final novel, Unless (2002) is the story of a teenager who leaves a loving home to beg on the streets of Toronto with a sign on her lap reading “Goodness.” It won B.C.’s Ethel Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize, but Shields was unable to accept the prize due to illness. Memorably, her daughter Anne Giardini accepted on her behalf and connected the audience with her mother by cell phone.

Carol Shields had significant collaborations with Blanche Howard and Marjorie Anderson. She had met the writer Blanche Howard during their Ottawa years. They met up again through the Literary Storefront in Vancouver and co-wrote a novel, A Celibate Season (1990), about a married couple who are separated by British Columbia’s recession – he remains in North Vancouver as a house-husband while she accepts work in Ottawa. Carol Shields and Winnipeg’s Marjorie Anderson co-edited the first of three volumes of Dropped Threads (Vintage), collections of essays by women from all across Canada about topics that had been dropped from the general discourse.

“They say you write the same novel over and over,” Shields once said, “and the idea of women being fully human has always been a preoccupation.”

Carol Shields also worked as an editorial assistant and editor for the journal Canadian Slavonic Papers (1973-1975), taught English and Creative Writing at the University of Ottawa (1976-1978), taught Creative Writing at UBC (1978-1980) and taught at the University of Manitoba from 1980 onwards until she was named Chancellor of the University of Winnipeg in 1996.

Carol Shields received fifteen honourary doctorates. Her novels won the Arthur Ellis Award (1988), the Marian Engel Prize for a writer in mid-career (1990), the Governor-General’s Literary Award (1993), and a National Book Critics Circle Award (1994). Her 1993 novel The Stone Diaries won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and a Booker Prize nomination, and was named a New York Times “Notable Book” and a Publishers Weekly “Best Book” for the year. In 2002, Shields received the Charles Taylor Prize for Literary Non-Fiction for her Penguin Lives biography, Jane Austen, chosen from among 154 entries.

In 2000, Carol Shields and her husband moved to Victoria where she died at age 68 on July 16, 2003, of breast cancer.

Anne Giardini, who provided the opening essay for Carol Shields: The Arts of a Writing Life (Prairie Fire), described her mother’s approach to death. “In recent months my mother’s cancer has kept her increasingly close to home. Her illness has made her if anything even more in need of the information and ideas and promise of books. She has lived somewhat longer than her doctors predicted, no doubt assisted by the ‘bibliotherapy’ administered by her dearly loved friend Eleanor Wachtel, who has provided her with a stream of judiciously selected books that are more nourishing than chicken soup, and as sustaining as love.”

Carol Shields was survived by her husband and children, John (1958), Anne (1959), Catherine (1962), Meg (1964) and Sara (1968).

Don and Carol Shields also lived in Vancouver for two stints: at 20th and Cambie for four months in 1957, then on Churchill near 49th Avenue from 1978 to 1980. Of all her novels, possibly The Box Garden is most replete with Vancouver references, such as Woodwards, the Swiss Chalet, New Westminster, UBC’s Natural Sciences and Fine Arts Buildings, the West Vancouver Consumer Action Group, West 19th Avenue, and Woolworth’s.

“Reading is, by definition, a solitary act,” she once noted, “and our society tends to look askance at those who pursue their pleasures in solitude. But 25 years from now I predict a rediscovery of the book as we know it. Suddenly people will be saying of books: how portable, how compact, how direct, how cost-effective, how intimate, how blessedly silent, how vivid, how enduring, how interactive, how revolutionary!”

A documentary film about Carol Shields aired on Access Network in 1985. She was briefly a writer-in-residence in Kingston in 1986, and briefly held the same position at the University of Winnipeg and at Douglas College, New Westminster in 1988. Room of One’s Own devoted a special issue to honour her in 1989 and that year she was also briefly writer-in-residence at the University of Ottawa.

She spent a sabbatical year in Berkeley, California in 1994-1995. Prairie Fire devoted a special issue to Carol Shields in 1995. A musical version of her novel Larry’s Party was directed by Richard Ouzounian and several other plays by Carol Shields have been produced. A somewhat cloying CBC Life & Times documentary was made shortly before she died.

Following the death of Carol Shields, Blanche Howard and Allison Howard edited A Memoir of Friendship: The Letters Between Carol Shields and Blanche Howard (Viking Canada, 2006), with a foreword by Anne Giardini. Allison Howard was the editor for the pair’s co-written novel A Celibate Season when Howard was 22 years older than Shields. The letters range over a period from 1975 to 2003.

Two of Shields’s daughters are also fiction writers. By 2015, Anne Giardini had published two novels and Sara Cassidy had published six books for children and short fiction and poetry. As well, Cassidy had become co-director of the Victoria Writers Festival and Giardini had become a second generation Chancellor at Simon Fraser University in 2014.

BOOKS:

The Collected Stories of Carol Shields (Random House, 2004)

Unless (Random House, 2002)

Jane Austen (Penguin, 2001)

Dressing Up for the Carnival (Random House, 2000)

Larry’s Party (Random House, 1997)

The Stone Diaries (Random House, 1993)

The Republic of Love (Random House, 1992)

Coming to Canada (Carleton University Press, 1992)

A Celibate Season (Coteau, 1991)- co-written with Blanche Howard

The Orange Fish (Random House, 1989)

Swann: A Mystery (Stoddar, 1987)

Various Miracles (Stoddart, 1985) – short stories

A Fairly Conventional Woman (Macmillan, 1982)

Happenstance (McGraw-Hill, 1980)

The Box Garden (McGraw-Hill, 1977)

Small Ceremonies (McGraw-Hill, 1976)

Intersect (Borealis, 1974) – poetry

Others (Borealis, 1972) – poetry

EDITOR:

Dropped Threads: What We Aren’t Told (Random House, 2001)

Dropped Threads 2: More of What We Aren’t Told (Vintage, 2003)

PLAYS:

Unless: The Play (CanStage, 2005)

Thirteen Hands and Other Plays (Vintage, 2002)

Departures and Arrivals (Blizzard, 1990, Vintage, 2002)

Fashion Power Guilt (Blizzard, 1995: Vintage, 2000) written with Catherine Shields

Not Another Anniversary (Blizzard Publishing, 1998), written with David Williamson

Women Waiting (CBC Radio Play, 1983)

CRITICAL WORKS:

Liminal Spaces: The Double Art of Carol Shields, (Cambridge College Publishing, 2008) by Alex Ramon

Carol Shields Issue (Prairie Fire, 1995), edited by Neil Besner and G.N.L.Jonasson

Carol Shields and the Extra-Ordinary (McGill-Queens University Press, 2007) edited by Dvorak and Jones

The Staircase Letters: An Extraordinary Friendship at the End of Life (Random House, 2008) by Arthur Motyer with Elma Derwin and Carol Shields.

A Memoir of Friendship: The Letters Between Carol Shields and Blanche Howard (Viking Canada, 2007 ).

Carol Shields: The Arts of a Writing Life (Prairie Fire, 2003) edited by Neil K. Besner

Carol Shields, Narrative Hunger, and the Possibilities of Fiction (University of Toronto Press, 2003) edited by Edward Eden, Dee Goertz.

The Worlds of Carol Shields (University of Ottawa Press, 2014), edited by David Stains

LITERARY AWARDS:

Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize, for Unless, 2003

Charles Taylor Prize for Literary Non-Fiction, for Jane Austen, 2002

Guggenheim Fellowship, 1999

The Pulitzer Prize, for The Stone Diaries, 1995

The National Book Critics Circle Award, for The Stone Diaries, 1994

Canadian Booksellers’ Association Prize, for The Stone Diaries, 1994

McNally Robinson Award for Manitoba Book of the Year, for The Stone Diaries, 1994

The Governor General’s Literary Award, for The Stone Diaries, 1993

The Marian Engel Award, 1990

The Arthur Ellis Award for Best Canadian Mystery, 1988, for Swann

National Magazine Award, 1985, for the short story ‘Mrs Turner Cutting the Grass’

First Prize, CBC Annual Literary Competition, for Women Waiting (a drama), 1983

Susanna Moodie: Voice and Vision, 1977

Canadian Authors Association Best Novel Award, for Small Ceremonies, 1976

Winner, CBC Young Writers Competition, for poetry, 1964

HONOURARY AWARDS, ETC.

Honourary Doctorate, University of Manitoba, Malaspina University and College, 2003

Companion of the Order of Canada, 2002

Queen Elizabeth Golden Jubilee Medal, 2002

Carol Shields Creative Writing Award established by Red River College and Manitoba Writers Guild, 2002

Honourary Doctorates, Lakehead University, University of Victoria, University of Calgary, 2001

Order of Manitoba, 2001

Winnipeg Citizen of the Year, 2001

Bust of Carol Shields by Eva Stubbs mounted on plinth in Assiniboine Park, 2001

Chancellor Emerita, University of Winnipeg, 2000

Honourary Doctorates, Carleton University, Wilfrid Laurier University, 2000

Professor Emerita, University of Manitoba, 1999

Carol Shields Winnipeg Book Award established, 1999

Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, 1998

Officer of the Order of Canada, 1998

Honourary Doctorates, University of Toronto, University of Western Ontario, Concordia University, 1998.

Honourary Doctorates, Hanover College, Queen’s University, University of Winnipeg, University of British Columbia, 1996

Honourary Degree, University of Ottawa, 1995

[Alan Twigg / BCBW 2015] “Fiction”

An Appreciation of Carol Shields by Linda Rogers:

When I first met Carol, she had recently published The Stone Diaries and I had reviewed it for the Vancouver Sun. Literally millions of women were recognizing themselves in the heroine Daisy, who came into the world through the dead body of a woman simultaneously producing a summer pudding.

In a conversation in my garden, where the peaches were ripening and falling on the lawn, Carol described her mother’s fussiness with peaches canned in blue jars and arranged, just so, in patterns that reflected her own idea of a universal design. As a child, she had been impatient with this perfectionism, but as she described the blue glass and the beautifully complementary golden peaches, we were directed to silence, realizing that this had been her mother’s art.

Carol Shields was born in 1935. Her mother was a teacher; her father was the manager of a candy factory. No outrageousness, no trauma, no precocity marked her childhood. She and her twin sisters had a regular pattern of eating, sleeping and going to the library. Perhaps no one noticed Carol was always thinking while she sucked those hard candies.

She graduated from Hanover College, the University of Exeter, and the University of Ottawa, and married Don, a professor of Civil Engineering, and had five children. When her children were grown, she taught at the University of Ottawa, UBC and the University of Manitoba. She later became Chancellorship Emeritus of the University of Winnipeg, after she had received off-hand treatment afforded to female faculty at another university.

Over the course of 13 books of fiction, three collections of poetry, numerous plays, a biography and two anthologies of non-fiction, Shield’s writing has matured the way fruit perfects itself in jars, in that cool dark room behind the eyes where women take refuge. Every observed ordinariness in her observation becomes extraordinary.

It is her understanding of the small events that allows Shields to make the imaginative leaps to universality that have made her one of the outstanding writers of her time, winning the Orange Prize, the Pulitzer Prize, the Governor General’s Award and the National Book Critics’ Circle Award.

Carol and Don Shields recently moved to Victoria. It had been their retirement plan to live in a condominium at Songhees on the beautiful inner harbour, near the Empress Hotel and Rattenbury-designed late Victorian Legislative buildings. The condo leaked and Carol developed breast cancer. At first, she refused to look in her bathroom mirror during the chemotherapy and radiation treatments that vanished her hair.

“The bathroom was walled in mirrors,” she says. “It took skill to bathe and brush my teeth without looking.”

Women are used to living their lives in mirrors, constantly looking for reassurance. Windows and mirrors are places of entry and exit throughout Carol’s canon. “Unless you can look in the mirror and see a benign and generous and healthy human being, you shrink from acts of hospitality,” says Elizabeth in ‘Dying for Love,’ a story in Dressing Up for the Carnival.

Eventually Carol apprehended herself, catching hold of her image, in its encircling flesh, and realized this disintegrating quilted envelope would accompany her to the end, and she had lost forever the power to stir ardour.

During her first convalescence, Carol chose to write a biography of one of the past masters of the art and artifice of women, Jane Austen (Penguin $28.99). Don Shields complained that Carol became Austen while researching and writing the book. One of her astonishing revelations is the likelihood that Austen also suffered from breast cancer. It is easy to imagine Shields as a reconstituted virgin, Austen-like, sitting at a secretary in the corner of some drawing room, listening and taking dictation from the events around her.

The American novelist Dawn Powell once wrote “the most important thing for a novelist is curiosity and how curious that so many of them lack it.” Carol Shields has always had an ear for dialogue and a fine eye for detail. When she praises people, she sometimes says they are “curious,” curious in the sense of information-obsessed; relentless investigators, like herself, like all good writers, like crows gathering shiny things in the garden.

Whether making love beside fragrant jasmine hedges, weeding the vegetables, or drying the healing herbs and the potpourri for trousseau chests, the lives of women in Shields’ fiction have frequently been lived and preserved in terms of the garden. The wilderness inside the enclosed garden is her provenance.

The Shields’ new house, in her own word, is “huge.” Carol was embarrassed to invite her Victoria friends there in the beginning. It takes forever to inhabit so many rooms, filling them with story. This is the feminine way to inhabit a house, through the realization of fantasy. It’s perhaps the reason why women make good realtors.

Now Shields is enduring a recurrence of cancer. Despite repeat chemotherapy, she still breathes life into words, advancing her own plot by sheer will. Carol Shields is running her huge house and “turning up” at artistic and literary events. She has even changed her dress code, “Wearing all those things I always wanted to wear,” letting the gypsy out, to the surprise and occasional horror of Don, who loves her as she is.

Ever curious, she flew to Toronto to the opening of the hit musical Larry’s Party, based on her book, and to Paris for the launch of her play “Treize mains” in French. There was no end to her

enthusiasm for new projects, including Thirteen Hands and Other Plays (Vintage $24.95).

In the afterward she says, “We move through our chapters mostly with gratitude…Surprise keeps us alive, liberates our senses. I thought for a while that a serious illness had interrupted my chaptered life, but no, it is a chapter on its own. Living with illness requires new balancing skills. It changes everything, and I need to listen to it, attend to it and bring to it a stern new sense of housekeeping.”

The woman who managed a handful of children and a trunk load of fiction was managing her transitions with grace. She allowed her husband and children to look after her. That is the chapter she is in. The house she manages now is the imaginary maison lumière, where her fictitious characters live and breathe.

If there is a greater audacity in the writing, it might be due to awareness of mortality. Most significantly, Carol Shields has written Unless (Random House $35.95) , with its perfect title for the always open possibilities of free will. The celebrated novel reveals the ironies of a woman’s life in a much bigger home, this world. It could have been invented by a Zen master, it is so perfectly a threshold.

Unless is as much a philosophical treatise as it is a novel. Her narrator Reta is a writer of minor profile. Shields gives her a quest. Reta believes she has lost her eldest daughter, Norah, the metaphorical granddaughter of Ibsen’s pre-feminist protagonist in The Doll’s House. Norah does the Norah thing. She leaves, and her mother is left dangling over the abyss of “how” and “why.”

Norah, the lost daughter, lives on the street in Toronto with a sign reading GOODNESS hanging around her neck. We don’t know why until the final revelation, but circumstances have driven Norah to question the balance of good and evil. What she is trying to understand is what St. Anselm believed, that evil is the absence of good. She has dissociated herself from conditional love, the boundary that defines family, community and culture, to go beyond borders.

All that matters is GOODNESS, the life force.

Unless is signature Shields. The onion peels layer by layer until the centre reveals itself. Unless transcends gender politics. It is a book about the human condition.

In one stunning chapter, Shields takes us to the outer boundaries of grief. Reta wants to buy a gift for Norah, something perfect like the child she knows. “The scarf became an idea; it must be brilliant and subdued at the same time, finely made, but with a secure sense of its own shape.” Reta is not a shopper, but she is relentless in her quest for the right thing. When she finds it, we begin to feel the possibility of redemption. Mother and daughter must find one another in perfect understanding, whatever the outcome.

Out of generosity, Reta follows her shopping trip by having lunch with her friend and fellow writer, Gwen, who like many artists has been reduced by the realities of the marketplace from altruism to jealousy. When she shows the scarf to her, Reta thinks Gwen understands, because she says, “Finding it, it’s almost as though you made it. You invented it, created it out of your imagination.” The scarf becomes, for one moment, more than silk. It constitutes a bond between women.

Gwen accepts the scarf for herself; Reta lets it slip through her fingers. This is a stunning and horrible moment in the book. We feel everything slip away: mother, child, the world itself. In this moment, Reta may or may not be betraying her daughter by letting her go when she thinks she ought to hold on. Grief is the silk scarf we drop, because we believe we must give whatever is asked of us. Sometimes goodness resides in denial. Perhaps Norah, who has forsaken the material world, is more evolved than her mother.

Unless is the essential book of a great writer and a great human. That Carol Shields has given so much of herself in order that we can move closer to the light is an extreme act of generosity.

[Linda Rogers / BCBW 2003]

An Appreciation of Carol Shields by Joan Givner

I read Carol Shields’ first novel in the fall of 1978. I can date the moment exactly because, although I have no copy of the fan letter I wrote then, I do have her reply—written on a manual typewriter, postage to the USA 14 cents. At the time Carol was living at 6607 Churchill St. in Vancouver and teaching creative writing at UBC; I was at Radcliffe College working on the life of Katherine Anne Porter.

Small Ceremonies went to the heart of my preoccupations of that time, for in Judith Gill, Carol has created a complete portrait of a biographer. Gill’s “lust” for other peoples’ stories forces her children to use protective strategies—locking diaries, taping closed their incoming mail. When she rents a house, Gill assembles the owner’s character from letters, kitchen utensils and the contents of bathroom cupboards. This is me all over, and the darts must have hit home.

Yet Carol makes her character, a literary biographer, both conscientious and insightful. As Gill works on Susanna Moodie, she experiences the scrupulous biographer’s guilt in exhuming another life. She frets about the interpretation of significant details, and sees her subject as a distant mirror in which she discerns her own image.

Carol could speak with authority on the subject, for she had served her own apprenticeship as a biographer. Her M.A. thesis was a biographical study of Susanna Moodie. When Carol discovered later that someone had stolen part of the Moodie archive, the theft inspired a second book—the mystery Swann.

When we eventually met, Carol and I found something else in common: in 1955 we had both been students at Exeter University in England. Carol was on a year’s exchange program from Hanover College in Indiana, and I was a first year undergraduate. We must have passed in the streets for it was a small campus then, and I was in the habit of staring at the American co-eds, conspicuous in saddle shoes and bobby socks, while the rest of us wore matronly tweed suits and nylons. Moreover I saw the student production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in which she played Cobweb—but memory refuses to speak.

Nevertheless I garnered one retrospective impression of Carol at Exeter: it is of her extraordinary single-mindedness about her future. There was no tension between marriage and career, or nervousness about juggling the two. She intended to marry and have children immediately, and she went ahead and did that. I link that sure sense of direction with her deftness in handling a plot. It bolsters my theory that there is a connection between a woman writer’s capacity to plot her own life and her capacity to plot her characters’ lives.

Over the years, our conversations during our sporadic meetings focused generally on life-writing. On one occasion I flew to Winnipeg to explore the possibility of writing a life of Dorothy Livesay. Because Carol knew Dorothy in Ottawa, we discussed key incidents in the poet’s life. But there was a difference now. Carol herself had become an acclaimed author and a subject for biography in her own right. My Winnipeg diary offers a split-screen version of that week, with equal space given to Livesay’s life and to Carol’s opinions.

After we both moved to British Columbia, meetings became more frequent. Old professional habits die hard, and I sometimes wondered if Carol thought that a superannuated version of Judith Gill was facing her across the lunch table. She tolerated questions and theories even when they were off the mark. Was she, I asked, predisposed to value marriage so highly by growing up with a pair of twins, and feeling incomplete as the only “single” in the family? No, that was not it, at all!

I knew she was working on a new novel, and the experience of reading Unless was for me one of both discovery and rediscovery. I’m struck again by Carol’s sure sense of purpose and the coherence of her vision over 25 years. The link between the first and the latest book is asserted with calm assurance in the opening statements. Judith Gill says “the thought strikes me that I ought to be happier than I am.” Reta Winter’s, in a lower register, says “It happens that I am going through a period of great unhappiness and loss just now.”

Not only is the tonal range wider in Unless but also the thematic reach. Surprisingly, there is a strong feminist thrust. It is not, I think, a belated awareness so much as a latent force finally “blurted out.” “Blurting is a form of bravery,” Reta says when she articulates the thought that women “fall into the uncoded otherness in which the power to assert ourselves and claim our lives has been displaced by a compulsion to shut down our bodies and seal our lips…” Because she is translating the memoirs of a French feminist, scraps of her subject’s theoretical “discourse” punctuate her personal observations. The presence here of a character who is a cross between, say, Simone de Beauvoir and Helene Cixous constitutes another kind of “blurting out.” It reveals the intellectual and literary influences, hitherto concealed in her fiction, that are abundantly evident in

Carol’s conversation.

In the small pantheon of women writers, comparisons to Jane Austen are inevitable. Sometimes this is sly “put down,” suggesting a narrow domestic focus at the expense of larger social issues. Carol, in her biography of Jane Austen, reveals a subject far more worldly than is generally acknowledged, and perhaps welcomes the comparison. Nevertheless, because of the centrality of biography to her work, her important literary foremother is Virginia Woolf.

Since Woolf’s father was a biographer, she grew up immersed in biography, and at the same time fiercely critical of Victorian biographies “dominated by the idea of goodness.” Woolf eventually wrote one serious biography and two mock biographies, all three brilliant in themselves but especially useful in shaping her theories about the portrayal of characters. The chief effect of writing biography on both Woolf and Shields is that it brings a particular focus to their representation of character. The similarity is underscored by the antiphonal effect of their voices on the subject:

“Life is not a series of gig-lamps symmetrically arranged; life is a luminous halo, a semi-transparent envelope.” (Woolf).

“A life is full of isolated events but these events if they are to form a coherent narrative, require odd pieces of language to cement them together. (Shields).

“Lives which no longer express themselves in action take shape in innumerable words.” (Woolf).

“…unless, with its elegiac undertones, is a term used in logic, a word breathed by the hopeful or by writers of fiction wanting to prise open the crusted world and reveal another plane of being…” (Shields).

Woolf believed that the ideal biography should combine both dream and reality, a combination she expressed as “a marriage of granite and rainbow.” Critics quickly seized the image as the perfect description for her own art. It seems to me to apply equally well to the art of Carol Shields—based solidly as it is in the daily world, and yet always suggesting an awareness of that other evanescent “plane of being.”

[Joan Givner / BCBW SUMMER 2002]

Leave a Reply