#603 Deep time to time slipping away

August 26th, 2019

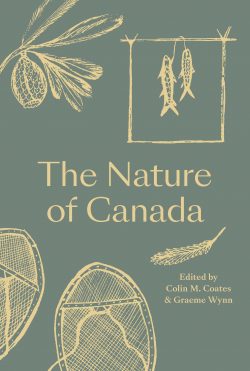

The Nature of Canada

by Colin M. Coates and Graeme Wynn (editors)

Vancouver: On Point Press, an imprint of UBC Press, 2019

$29.95 / 9780774890366

Reviewed by Jenny Clayton

*

A collaborative effort by some of the leading scholars in the field, The Nature of Canada offers a fresh look at Canadian environmental history. Wishing to showcase research supported by NiCHE, the Network in Canadian History and Environment, editors Colin M. Coates and Graeme Wynn asked scholars to write about the nature of Canada through a variety of lenses, such as the history of communication, energy, gender, scale and climate change. Contributors have interpreted their tasks creatively and concisely. Divided into fifteen chapters, the book explores a wide range of topics. At the end of each chapter, I was impressed by how much each author was able to cover and how they brought together case studies from various regions of the country. Most chapters whet my appetite to know more about particular topics, and they provide the means to do so with detailed “References and Further Reading” sections. Seeking to create a collection of “lively, wide-ranging, thought-provoking, and informative reflections on topics of broad significance to Canadians in the twenty-first century,” the editors and contributors have certainly accomplished these goals.

A collaborative effort by some of the leading scholars in the field, The Nature of Canada offers a fresh look at Canadian environmental history. Wishing to showcase research supported by NiCHE, the Network in Canadian History and Environment, editors Colin M. Coates and Graeme Wynn asked scholars to write about the nature of Canada through a variety of lenses, such as the history of communication, energy, gender, scale and climate change. Contributors have interpreted their tasks creatively and concisely. Divided into fifteen chapters, the book explores a wide range of topics. At the end of each chapter, I was impressed by how much each author was able to cover and how they brought together case studies from various regions of the country. Most chapters whet my appetite to know more about particular topics, and they provide the means to do so with detailed “References and Further Reading” sections. Seeking to create a collection of “lively, wide-ranging, thought-provoking, and informative reflections on topics of broad significance to Canadians in the twenty-first century,” the editors and contributors have certainly accomplished these goals.

The book begins with two chapters by Graeme Wynn, exploring Canada’s deep past, and how the land is represented through maps. In “Nature and Nation,” Wynn explains how ancient geological and ecological developments shaped Canada’s success, for example making certain areas suitable for farming and leaving deposits of various minerals that have become valuable for exchange in the global market. This chapter shows that we must pay attention to how nature, alongside political and economic forces, shapes nations.

In the next chapter, Wynn compares three maps of the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Valley. Based on Samuel de Champlain’s travels, the first map showed enthusiasm towards North American nature and a reliance on Indigenous residents. The second map, depicting the St. Lawrence Seaway and Power Project, was an idealistic portrayal of humans’ ability to remake nature into an “engine of growth and development” (p. 70). The third map, by Anishinaabe artist Bonnie Devine, adds new layers representing Indigenous history and colonialism to a map from 1842 by painting rivers red and animating the Great Lakes with mythical beings, showing promises that were broken, and conflict between Indigenous people and newcomers.

Several chapters, including the essay by Julie Cruikshank, explore the value of telling stories about the history of nature in Canada. Cruikshank draws on her interviews with Indigenous Yukon elders to point to some of the limits of Western scientific knowledge and the advantages of “listening for different stories” from people who have an intimate and longstanding relationship with the land. These stories, Cruikshank has found, depict nature as sentient and responding to human actions or disrespect, ideas that hold increasing weight in dealing with the climate crisis.

Lowell Glacier, known as Naludi (Fish Stop) in Southern Tutchone language. Photo by Julie Cruikshank

The following three essays engage with themes of integrating northern North America into world markets, and the long-term repercussions of the Columbian Exchange as plants, livestock and microbes were introduced to the Americas from Afro-Eurasia. “Eldorado North?” by Stephen J. Hornsby and Graeme Wynn, is a clear and detailed history of the cod fishery and the beaver pelt trade. These two resources drew European traders and settlers to this territory, “recast Indigenous lives, and laid the foundations for further economic, demographic, and sociopolitical development” (p. 102). Assessing how different scales of management may have impacted cod stocks and beaver populations, Hornsby and Wynn recognize the value of both local knowledge and the broader systematic view attainable with scientific methods.

“Back to the Land,” by Colin Coates, analyzes Canadians’ longstanding desire to make an independent living through agriculture. Displacing Indigenous cultivation, European forms of agriculture were a “second nature” that made an enormous impact on landscapes and ecosystems, to the degree that “most Canadians would be unable to tell the difference between introduced plant and animal species and indigenous ones.” (p. 136) Wynn’s “Nature We Cannot See,” is a wide-ranging and thought-provoking overview of the history of pathogens in Canada. This chapter, which surveys the impact of smallpox on Indigenous populations, cholera in growing nineteenth century cities, and poliomyelitis in mid-twentieth century suburbs, and concludes with modern diseases such as HIV/AIDS and SARS, helps us to think in new ways about disease vectors, local and global responses, and the social and psychological impacts of such diseases.

Michèle Dagenais

Canadian visions of “wild” and urban spaces are examined in chapters by Claire Campbell and Michèle Dagenais. Campbell engages with the idea of wilderness as a social construction that is central to Canadian identity. Not only do many of us identify with wilderness, but we also assume a kind of ownership of it, sharing a “nationalist conceit,” as Campbell writes, “that all that territory is my birthright” (p. 168). This idea of wilderness is remarkably flexible, allowing Canadians to imagine a healthy, pure wilderness existing in such abundance that there is ample room to exploit it for oil, gas, minerals, wood, etc. By the twenty-first century however, it has become increasingly difficult for Canadians to see ourselves as stewards of the wilderness. Although “wilderness” is a popular topic among environmental historians generally, scholars could pay more attention to the environmental history of cities, especially given the significance of urban spaces as sites of consumption and pollution. Dagenais’ article is therefore a valuable addition to this collection. The chapter is neatly organized around three models that influenced city planning — the garden city, the suburb, and the sustainable city, each of which sought to make cities better places to live. In exploring the history of each model, Dagenais asks who they served and how we can create more equitable cities.

Mining, communications, and energy are the foundations of the next three chapters. Arn Keeling and John Sandlos look at the environmental impacts of mining and its associated infrastructure. Given the ubiquity of the products of mining in Canadian households, Keeling and Sandlos argue that we should all have an interest in the impacts of this industry, including the “afterlife” of mines, in which the cost of clean-up can sometimes exceed a mine’s profits. “Every Creeping Thing” by Ken Cruikshank is one of the more creatively conceived chapters. Assigned the topic of “communications and the nature of Canada” (p. 238), Cruikshank discusses how various communication and transportation corridors, such as railways, roads, airports, microwave/radio and cell phone towers have affected ecosystems and species. In “The Power of Canada,” Steve Penfold argues that energy is a “socionatural creation” in which various types of energy have been put to use by Canadians to perform needed work. This chapter considers the consequences of various types of energy use, asks how distinctive Canada’s energy history is, and explores the ways that natural processes still define our access to energy and the ability to develop it.

Always a red button issue. W.A.C. Bennett opening the Peace River Power Dam project, July 1964. Deni Eagland photo

In “Questions of Scale,” Tina Loo builds on her earlier work on dam construction and high modernism to provide a national overview of postwar megaprojects, showing patterns unfolding across the country. The planners of hydroelectric dams, whether in B.C. or New Brunswick, envisioned “people in the way” of transitioning to a modern way of life. Dam building could also politicize those who were displaced, such as the James Bay Cree, who created the Grand Council of the Crees to protect their rights when faced with the flooding of their lands. Loo argues that high modernism was both destructive and creative, but that its broad vision can be valuable. Since “life is not lived on one scale” it is important to pay attention “to the connections among scales” (p. 276) to address global challenges such as climate change.

While much of the book discusses Canadians’ acquisitive treatment of nature, the next two chapters focus on environmental activism. “A Gendered Sense of Nature” by Joanna Dean is a refreshing and original take on a topic that has not received much attention in Canada — environmental history through a gendered lens. In a neatly focused essay, Dean compares the feminine Voice of Women and the male-led Greenpeace to show how these two organizations used maternal and paternal arguments to raise awareness of the impacts of radioactive fallout on women’s and men’s bodies and their ability to reproduce. Graeme Wynn and Jennifer Bonnell choose a biographical approach to explore how one influential environmentalist, David Suzuki, has reflected and shaped Canadian environmental consciousness (Editor’s note: see a forthcoming number of the Ormsby Review for a reprint of this chapter).

The urgent issue of climate change has a subtle influence on several chapters and is the central theme in the last two. Liza Piper’s nuanced and informative chapter on long term climate change will be much appreciated by students of environmental history. This chapter discusses causes and effects of temperature fluctuations since the last Ice Age, and shows how Canadians have observed, recorded, and thought about climate change over time. The chapter I found most compelling and beautiful was the final one by Heather E. McGregor, “Time Chased Me Down, and I Stopped Looking Away.” Set within the context of a High Arctic cruise, and inspired in part by Roy Scranton’s Learning to Die in the Anthropocene, this chapter raises important and uncomfortable questions. In reference to melting glaciers, McGregor asks, “Is this a crisis or is this just life? Are life and crisis the same thing?” (p. 345). Of particular interest to historians, she asks how historical research can contribute, when Northerners need to adapt to the future now.

The Nature of Canada is an attractive book, with illustrations underlining various points and telling side stories that may not have fit directly into the narrative. A photograph of young polio victims, bundled up on a lawn in Fredericton, brings to mind a fairly recent affliction that “helped to change attitudes and win new rights and services for the disabled” (p. 155). A dramatic photograph taken by Tina Loo of a cement plant adjacent to Banff National Parks highlights “the industrial sublime,” a central theme of this book. Arresting photographs by Edward Burtynsky and T.J. Watt of open-pit mining and clear-cut logging raise questions about how Canadians can accept such resource extraction activities and how these landscapes could ever be restored.

As the editors point out, this book does not intend to be a comprehensive history of this field and not every topic could be included. Yet there is very little missing here; topics that could be explored in more detail, for example, are forestry and the pollution of air and water. Chapter themes no doubt depend on the historians who were available to participate. Given the importance of climate change to this volume, it would have been worthwhile to address the tar sands/oil sands in more detail and Canada’s shifting position on climate change on the global stage.

Overall, this is an extraordinary book that in one dynamic volume summarizes the rich and growing field of Canadian environmental history. Offering broad comparisons, fresh perspectives, and cutting edge research in an increasingly relevant field, this book will be an essential resource for Canadian historians and students of environmental history.

Woodland caribou in the southern Yukon Territory. An image from Julie Cruikshank’s contribution. Photo by Dean Biggins

*

Jenny Clayton teaches courses on Canadian and environmental history at Camosun College and the University of Victoria. She has recently published The Lieutenant Governors of British Columbia (Harbour, 2019).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply