#584 Brother artist at the edge

July 26th, 2019

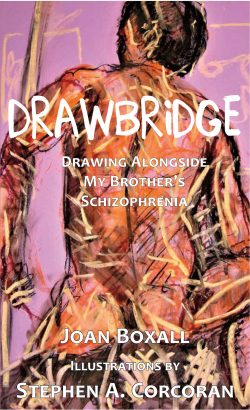

Drawbridge: Drawing Alongside My Brother’s Schizophrenia

by Joan Boxall

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2019

$24.95 / 9781773860022

Reviewed by Janet Nicol

*

A memoir told in ten lyrical essays, Drawbridge: Drawing Alongside My Brother’s Schizophrenia is Joan Boxall’s moving tribute to her brother, Stephen Corcoran. In the early 2000s, Joan became co-trustee of Stephen following the death of their parents. So began her enlightening ten-year journey supporting a brother with a mental illness. Joan intersperses research, observations, and thoughts with her poetry, each essay framed within a theme of art — the powerful tool that provided a path for Joan and Stephen to connect.

A memoir told in ten lyrical essays, Drawbridge: Drawing Alongside My Brother’s Schizophrenia is Joan Boxall’s moving tribute to her brother, Stephen Corcoran. In the early 2000s, Joan became co-trustee of Stephen following the death of their parents. So began her enlightening ten-year journey supporting a brother with a mental illness. Joan intersperses research, observations, and thoughts with her poetry, each essay framed within a theme of art — the powerful tool that provided a path for Joan and Stephen to connect.

At the time of re-uniting, Stephen was living independently in a rented apartment on Vancouver’s southeast side and Joan lived with her husband on the North Shore. She attended a mental health symposium and learned, among many things, that she was assuming the role of family peer counsellor. Joan paints a picture of a brother who talked to himself, heard imaginary voices, and wheeled his possessions in a buggy along the street. Here’s what winding down a day might have looked like for Steve:

Clearing space on the bed, he eats a slice [of pizza] while looking at a graphic novel he picked up in a free-book bin. He puts on a second pair of glasses (overtop of the first). He gets up to open the iced-over fridge, takes a can of beer from the door, pulls the tab, takes a long swig, props himself against a grubby pillow, leafs through one of the books, pops a lithium, takes another swig and then falls asleep, fully clothed.

Joan confronted her brother’s vulnerability in many ways, confessing that when she listened to the news, for instance, she worried that Stephen was either the victim or the perpetrator of a reported violent crime. She also recounts a story about bullies who taunted Stephen and spray-painted a dumpster near his apartment. Still, she offers a wise, philosophical approach in her perceptions of her brother’s life.

The author traces her own life story alongside Stephen’s, from her student days at the University of British Columbia to a teaching career and marriage. She also provides flashback accounts of growing up on Vancouver’s west side in the 1960s, within a family of seven children. The reader eventually learns that when Stephen experienced a psychotic break as a young adult, he was married with two young children, working at a mill, studying at Vancouver School of Art, and training as a welder. Because of his mental illness, Joan writes, “he lost his livelihood, his family and his dream.”

Stephen’s long-time doctor described him as having “loose associations, also known as a type of mania or thought disorder.” (As Joan points out, in some circles this is known as creative thinking.) By the time Joan and Stephen re-connected, he was in stage three of schizophrenia, the psychoses, hallucination, and delusion in decline.

When Joan came across a brochure about The Art Studios, an organization supporting people with mental illness and addiction, she suggested that Stephen attend classes, and then she went along in the role of observer. As the lessons started to give Stephen a positive outlet, Joan encouraged him to eat healthier food and to appreciate the social graces, such as pouring a drink for another person — and saying thank you. When she listened to her brother’s rants in the third person (and even dreamed about them), she did not know how to respond. She observed his studio instructor Ann would react by saying, “Let’s not talk about that right now,” or “we will come back to that later.”

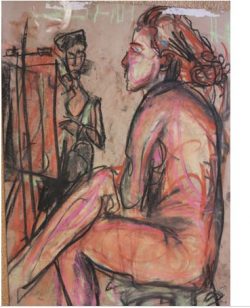

After Stephen had taken all the classes that interested him, the pair transitioned to Basic Inquiry, a decades-old artist-run collective on Vancouver’s Main Street. The three-hour sessions with a live model do not permit observers, and so Joan began participating alongside her brother and other artists. She describes the moment when the model disrobes and the artists begin drawing “like a conductor raising his baton. We orchestra members sit taller and put drawing tool to paper, like bows to violins.”

Every piece of art Stephen created was distinctly his. Through his confident marks, he was “…silently showing me his artistic self, and more indirectly, an artistic path — open to all.” Several of Stephen’s female nudes, done in chalk pastel, conte crayon, and charcoal are included in the book. A few drawings show the outline of the figure re-traced in three different colours, creating a dramatic effect. A drawing of a pair of pink shoes with black laces — likely the artist’s — is playfully layered with orange scribbled lines.

When a model told Stephen she liked his rendition of her, he gave her the drawing. It was among the small but satisfying social interactions Joan witnessed. She found that drawing nude figures worked for her brother, making him lighter and freer. Joan took on the task of matting and framing Stephen’s pieces, seeing joyful surprise, with only occasional anger, expressed in his work.

A person fully engaged in creating art in a “clear, serene and timeless way,” experiences ecstasy

, Joan notes, a word from the Greek meaning “being outside body or mind.” “For Steve, putting himself aside is restful,” she believes. “This is where he wants to be.” Stephen’s remarkable paintings and drawings would be displayed in two solo exhibits at Basic Inquiry Gallery.

“Who sees death coming?” Joan asks in the ninth chapter of her collection. Her brother was diagnosed with cancer and after a short illness died in 2013, aged 64. Joan’s concluding chapter speaks to Stephen’s legacy and impact. “I started out as Steve’s rep but he became mine,” she realizes. “We each turn out to be part hero, part mentor, part helper and part hinderer like everyone else.”

Joan has established the Stephen A. Corcoran Award at Emily Carr University of Art and Design, a bursary supporting students who are living with mental health issues. There are more than 200 kinds of mental illness, Joan points out, and mental health challenges affect one in five Canadians. Those of us not affected, she suggests, might be compelled to do something about it, as she most certainly has in many profound ways.

A bibliography to Drawbridge provides a wide range of resources, indicating the author’s detailed research. There are photographs as well. The spirited generosity of these shared stories is best captured in a photo of Stephen and Joan standing side by side at a city park on a sunny day, both smiling broadly into the camera lens.

*

Janet Mary Nicol is a freelance writer and retired high school teacher. On the Curve: The Life and Art of Sybil Andrews was recently published by Caitlin Press. Her writing blog is at http://janetnicol.wordpress.com/

Janet Mary Nicol is a freelance writer and retired high school teacher. On the Curve: The Life and Art of Sybil Andrews was recently published by Caitlin Press. Her writing blog is at http://janetnicol.wordpress.com/

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply