#140 Margaret Craven

March 09th, 2016

LOCATION: Kwakwaka’wakw community of Kingcome Inlet, located about 500 kilometres north of Vancouver, and five kilometres up a shallow fjord.

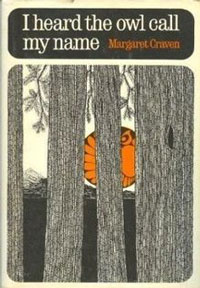

Margaret Craven’s bestseller set in Kingcome Inlet, I Heard the Owl Call My Name (1967), prompted a 1973 movie starring Tom Courtenay and Dean Jagger, directed by Daryl Duke. The community is located on an inlet with the same name, north and east of Broughton Island. I Heard the Owl Call My Name was inspired by the life of Anglican missionary Eric Powell. In the novel, Mark Brian, a missionary with three years to live, absorbs the wisdom and language of the Kwakwaka’wakw and learns they are “none of the things one has been led to believe. They are not simple, or emotional, they are not primitive.” While dying, Brian witnesses the disintegration of Kwakwaka’wakw society due mainly to liquor and residential schools.

To complicate matters, an English anthropologist arrives with limited understanding of the Kwakwaka’wakw. At the same time, the government prohibits traditional potlatch ceremonies. When the missionary hears the owl call his name, he knows he must soon die. His bishop arrives, promising to replace him, but Mark Brian decides to stay and die at Kingcome Village.

Although the novel received praise as a sympathetic rendering of aboriginal dilemmas in the 1960s, the protagonist is white and Craven’s knowledge of Kwakwaka’wakw culture borders on superficial. The movie version nonetheless constituted a cultural breakthrough as an attempt to tell a realistic story within the context of a contemporary First Nations community of British Columbia.

Although the novel received praise as a sympathetic rendering of aboriginal dilemmas in the 1960s, the protagonist is white and Craven’s knowledge of Kwakwaka’wakw culture borders on superficial. The movie version nonetheless constituted a cultural breakthrough as an attempt to tell a realistic story within the context of a contemporary First Nations community of British Columbia.

FULL ENTRY:

Set in the remote Kwakwaka’wakw community of Kingcome Inlet, located about 500 kilometres north of Vancouver, and five kilometres up a shallow fjord, Margaret Craven’s bestseller I Heard The Owl Call My Name (1967) prompted a 1973 movie starring Tom Courtenay and Dean Jagger, directed by Daryl Duke.

Other books and stories by B.C. authors that were the basis for movies include Bertrand Sinclair’s Whiskey Runners (1912), Shotgun Jones (1914), The Cherry Pickets (1914), Big Timber (1917), North of 53 (1917) and The Raiders (1921); Guy Morton’s The Black Robe (1927); Lily Adams Beck’s The Divine Lady: A Romance of Nelson and Emma Hamilton Divine (novel 19__ / movie 1929) won an Oscar for its director Frank Lloyd; Alex Philip’s The Crimson Tide (1925) became The Crimson Paradise (1933); Hammond Innes’ Campbell’s Kingdom (novel 1952 / movie 1957, starring Dirk Bogarde); Arthur Mayse’s Desperate Search (1953); Rohan O’Grady’s Let’s Kill Uncle (1963); Jane Rule’s Desert of the Heart (1964); Paul St. Pierre’s Breaking Smith’s Quarterhorse (1966); Tom Ardies’ Russian Roulette (1975) which was based on Kosygin is Coming (1974); William Gibson’s The New Rose Hotel (story, 1981), Johnny Mnemonic (story 1981 / movie 1995); W.P. Kinsella’s Shoeless Joe (1982); Evelyn Lau’s Runaway: Diary of a Street Kid (1989); Edith Iglauer’s Navigating the Heart which was based on her memoir Fishing with John (1988); Michael Turner’s Hard Core Logo (1993); Gary Ross’ Larger Than Life (1996) based on At Large: The Fugitive Odyssey of Murray Hill and his Elephants (1992), Owning Mahowny (2003) based on Stung: The Incredible Obsession of Brian Molony (1987); Maureen Medved’s The Tracey Fragments (2007); and Billie Livingston’s Sitting on the Edge of Marlene (2014).

Anne Cameron’s script Dreamspeaker (1977) was made into a movie before it became the basis for a novel, Dreamspeaker (1979).

I Heard The Owl Call My Name was inspired by the life of Anglican missionary Eric Powell. In the novel, a vicar with three years to live absorbs the wisdom and language of the Kwakiutl (Kwakwaka’wakw) and learns they are “none of the things one has been led to believe. They are not simple, or emotional, they are not primitive.” While he is dying, the missionary named Mark Brian simultaneously witnesses the disintegration of Kwakiutl society due mainly to liquor and residential schools. To complicate matters, an English anthropologist arrives with limited understanding of the Kwakiutl and the government intends to eradicate the potlatch ceremony. When the vicar hears the owl call his name, the missionary knows he must soon die. His Bishop arrives, promising to replace him, but Mark Brian decides to stay and die at Kingcome Village. Although the novel received praise as a sympathetic rendering of Aboriginal dilemmas in the 1960s, the protagonist is white and Craven’s knowledge of Kwakwaka’wakw culture borders on superficial. The movie version nonetheless constituted a cultural breakthrough as an attempt to tell a realistic story within the context of a contemporary First Nations community of British Columbia.

Born in Helena, Montana in 1901, Margaret Craven grew up in Puget Sound in Washington State determined to be a writer. She graduated from Stanford University, a member of the Phi Beta Kappa society, and worked for three decades as a journalist, writing an editorial column for the San Jose Mercury for six years. She published her first novel at age 69. A follow-up novel four years later and an autobiography in 1977 failed to gain much notice. Craven died in 1980. A collection of her heart-warming stories, mostly published in the Saturday Evening Post and dating back to the 1940s, appeared posthumously in 1981.

[Other books and stories by B.C. authors that were the basis for movies include Bertrand Sinclair’s Shotgun Jones (1912), Whiskey Runners (1912), North of 53 (1914), Big Timber (1916); Guy Morton’s The Black Robe (1927); Lily Adams Beck’s Divine Lady (1924); Rohan O’Grady’s Let’s Kill Uncle (1963); Jane Rule’s Desert of the Heart (1964); Paul St. Pierre’s Breaking Smith’s Quarterhorse (1966); W.P. Kinsella’s Shoeless Joe (1982); Edith Iglauer’s Fishing with John (1988); Evelyn Lau’s Runaway: Diary of a Street Kid (1989)

BOOKS

Craven, Margaret. I Heard the Owl Call My Name (Clarke, Irwin, 1967; NJ: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1973).

Craven, Margaret. Walk Gently This Good Earth (Putnam, 1977).

Craven, Margaret. Again Calls the Owl (Putnam, 1980).

Craven, Margaret. The Home Front: Collected Stories (Putnam, 1981).

Leave a Reply