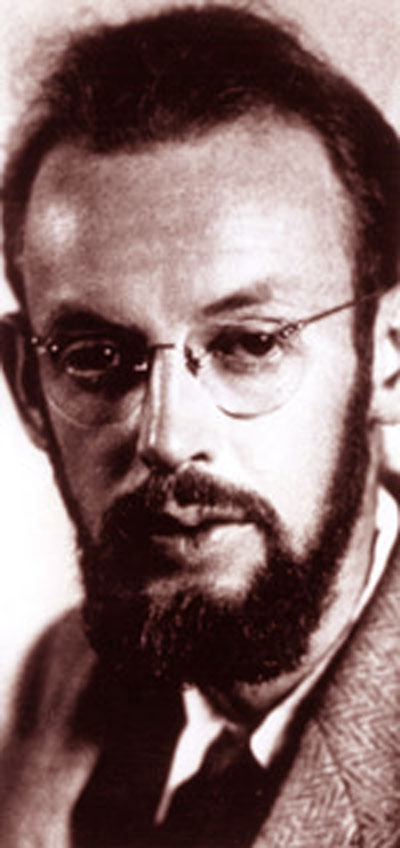

#104 Earle Birney

February 02nd, 2016

LOCATION: “Lieben” Writers Colony, ten acres of now forested land situated below 1390 Eaglecliff Road, Bowen Island. DIRECTIONS: From Snug Cove ferry terminal, proceed up the hill on Bowen Island Trunk Road, right onto Miller Road, left onto Scarborough which becomes Eaglecliff.

Formerly an artists’ retreat owned and shared by Einar Nielsen, this once much-frequented property was donated by the Nielsens to the province of B.C. with the proviso that it never be developed, largely because Einar Nielsen was appalled by real estate speculators. There is no signage, no plaque. Earle Birney, the most influential B.C. author of the ’40s and ’50s, was a mainstay at the communal writing retreat on Bowen Island called Lieben. Neilsen and his wife hosted dozens of artists including writers Eric Nicol, Dorothy Livesay, Malcolm and Margerie Lowry, Ben Maartman and B.C.’s first literary book publisher William McConnell. In the 1940s Birney also had a beachfront shack called Three Bells in Dollarton, nearby his friend Malcolm Lowry’s more famous abode. Birney was the galvanizing force of his era. “The history of the development of contemporary writing in Vancouver from 1946 to 1960,” said Earle Birney, “is pretty largely a one-man show, and that man was me.”

QUICK ENTRY:

With Roy Daniells, Earle Birney co-founded Canada’s first accredited Creative Writing Department at UBC, and he wrote one of the most-anthologized poems in Canadian literature, “David,” about the death of a hiking companion. Also a poet, novelist, editor, professor, dramatist, political activist, Chaucer scholar and womanizer, Earle Birney was British Columbia’s most central and pivotal literary figure of the 20th century. Although he was peerless and much appreciated as a literary catalyst, biographer Elspeth Cameron has alleged Birney’s skills as a self-promoter and organizer were the foundation of his success and his second wife Esther Birney eventually scorned him as, “the most irascible man that moral woman was ever tormented with.”

Born in Calgary in 1904, Earle Birney mainly grew up in Creston, B.C. where he was reared on The Bible, John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress and the poetry of Robbie Burns. He had what would later refer to as “a solitary and Wordsworthian childhood.” Inadequate at sports but a social climber, the lanky, carrot-topped teen (“dazed with lust”) rejected a banking career in Vernon, B.C. and headed for a brothel to be deflowered at 17.

Birney enrolled in chemistry at UBC until he was encouraged by Harvard-educated Garnett Sedgewick, “the man of all men who had stood nearest in the role of father to me.” With Sedgewick’s help, Birney would return to Vancouver and teach medieval literature at UBC from 1948 to 1965 when he became the first Writer in Residence at the University of Toronto.

Birney received Governor General’s Awards his poetry collections David and Other Poems (1942) and Now Is Time (1945). Ensconced at UBC, Birney increasingly turned his hand to experimental poetry and verse play. Some of his most enduring works are Trial of a City (1952), Near False Creek Mouth (1964) and The Damnation of Vancouver (1977). While enthusiastic about a new generation of poets that included Leonard Cohen and bill bissett, Birney had severe reservations about the TISH movement engendered by American poetry professor Warren Tallman. “They introduced cultism in its extreme form,” Birney once wrote. “Anything written unlike what they were writing was dubbed not just inferior, but Anti-poetry. How the Puritan mind is reborn in every new movement.”

In 1933 Birney married fellow Trotskyite Sylvia Johnstone but their marriage was later annulled. He worked on a tramp freighter to reach London where he completed his doctoral thesis on Chaucer, researching at the British Museum and working for the Independent Labour Party. He went to Norway to interview Leon Trotsky, his political hero, in 1936. Having been an organizer for the Trotskyite branch of the Communist Party during the 1930s, Birney later wrote a Vancouver-based Depression novel, Down the Long Table (1955), at the end which the reader is made aware it’s a memoir prompted by the protagonist’s appearance before a red-baiting hearing during the McCarthyite purges of the 1950s.

In Berlin, Birney met up with Esther Heiger, who had married Izrael Hieger. Born Esther Bull, of Russian-Jewish descent, the idealistic pair lived like gypsies in Dorset where Esther, recently divorced, helped him complete his 860-page thesis on Chaucer’s irony. Esther came to Canada where they had one child together. Birney was never a diligent father. “We got married for the sole purpose of giving the child legitimacy,” Esther Birney has recalled. “We both thought that marriage was a bourgeois institution having to do with property and possessions. We had a Marxist beginning and set out to live according to the Communist Manifesto. We believed you don’t possess people. For this reason, neither of us objected to affairs.”

Birney had prolific love life. Throughout his adult life he was sexually active with countless women including Carlotta Makins, Margaret Crosland and Liz Cowley. A large percentage of his lovers remained intimate friends. “I know full well that I brought genuine love to those women which is still with them and which they draw strength from to this day,” he once wrote. As a professor, he encouraged gifted female students such as Phyllis Webb, Betty Lambert, Heather Spears, Marya Fiamengo and Rona Murray, and was not always able to limit his attentions to teaching. Birney linked his creativity with virility.

In 1973, after his heart attack at age 69, Birney began cohabiting with a beautiful 24-year-old Cantonese graduate student, Wailin (Lily) Low. This became his greatest love affair. After Birney suffered a near-fatal fall while climbing a tree in July of 1975—at age 71—Wailin lovingly nursed him back to health and revitalized his spirits and his writing. Earle Birney and Esther Birney finally divorced in 1977 on the grounds of adultery, ending an unusual 37-year marriage. Wailin Low remained at Birney’s side after he suffered another near-fatal heart attack in 1987. She was steadfastly caring and protective when Birney was a long-term patient at Toronto’s Queen Elizabeth Hospital with a disabling brain injury. Earle Birney died in Toronto on August 27, 1995. Wailin Low, now a judge in Ontario, has continued to control his literary affairs.

Earle Birney developed literary relationships over the years with Lister Sinclair, E.J. Pratt, Louis Dudek, Lorne Pierce, Alan Crawley, Ralph Gustafson, Clyde Gilmour, Fred Cogswell, F.R. Scott, John Adaskin, Northrup Frye, Claude Bissell, Morley Callaghan, Robert Weaver, Jack Shadbolt, Anne Marriott, Roderick Haig-Brown, Bill McConnell, P.K. Page, Ethel Wilson, Paul Engle, Mirian Waddington, W. Kaye Lamb, Jack McClelland, Irving Layton, Stephen Vizinczey and Leonard Cohen, to name only a few. In Vancouver, Birney also befriended newcomers Malcolm Lowry and George Woodcock, and became a central personality in an unofficial writers’ colony that existed on Bowen Island, hosted by Einer Neilson. Birney organized visits by Dylan Thomas, Theodore Roethke, Charles Olson and W.H. Auden, among others. He supported and encouraged countless writers and students such as Jack Hodgins, Tom Wayman, Daryl Duke, Norm Klenman, Heather Spears, George Bowering, Norman Newton, Frank Davey, George Johnston, Bill Galt, Lionel Kearns, Mary McAlpine, Daphne Marlatt, Ernie Perrault and Robert Harlow (who became Head of the Creative Writing Department). Earle Birney was also good at making enemies. In the 1970s, his fellow poet and leftist radical Dorothy Livesay told anyone who would listen that Birney’s much-anthologized poem ‘David’ was autobiographical and that Birney was, in effect, a murderer.

ENTRY:

Alfred Earle Birney was British Columbia’s most central and pivotal literary figure in the 20th century. As a poet, novelist, editor, professor, dramatist, political activist and Chaucer scholar, Birney directly influenced many writers in his role as the first director of UBC’s Creative Writing Department, the first accredited department of its kind in Canada.

Birney was born on Friday the 13th, May, 1904 in Calgary when it was still part of the Northwest Territories. Will Birney, his father, had come west on horseback and met Martha Robertson, daughter of a Shetland fisherman. Birney was raised on a remote, ten-acre bush farm near Lacombe, Alberta, until at age seven when he was taken to the Shetland Islands where he caught pneumonia. Birney had what he later called “a solitary and Wordsworthian childhood.” He was reared on The Bible, John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress and the poetry of Robbie Burns.

He returned to Alberta to live for one summer in a tent on the banks of the Bow River until his father completed building a home in Banff in 1911. After his father served in World War I, the family moved to a fruit farm near Creston, B.C. “I was constantly being rejected by the group because I was no bloody good in team sports,” he once said. Something of a know-it-all, a social climber and a sissy, the lanky, carrot-topped teen (“dazed with lust”) rejected a banking career in Vernon and headed for a brothel to be deflowered at 17. After high school he had jobs as a bank clerk, farm labourer and government worker for a mosquito control project.

Participating in the Great Trek in 1922 (that led to the creation of UBC), he enrolled at UBC in chemistry, living in an attic at Columbia and 11th Ave. He thought he might become a chemical engineer. He was encouraged to consider a career as an academic by Harvard-educated Garnett Sedgewick. Birney had a fractious stint as the editor of the student newspaper Ubyssey in 1925 prior to his removal from the post by the university administration. He graduated with a B.A. in Honours English in 1926. He received his Masters from the University of Toronto in 1927, then did graduate studies at Berkeley in California, living on Telegraph Hill. Birney took a teaching job at the English Department of the Mormon-run University of Utah in 1930 and studied for his doctoral degree at the University of Toronto in 1933.

In Toronto he met fellow poet and leftist radical Dorothy Livesay, then a Stalinist. Half a century later, the ever-volatile Livesay would assert that Birney’s much-anthologized poem about a mountain climbing death, ‘David’, was autobiographical and that Birney was, in effect, a murderer.

Birney became an organizer for the Trotskyite branch of the Communist Party during the 1930s. He later wrote a Vancouver-based Depression story of his Trotskyite days, Down the Long Table. Only at the end of the novel is the reader made aware that Down the Long Table is a memoir prompted by its protagonist’s appearance before a red-baiting hearing during the McCarthyite purges of the 1950s. Gordon Saunders, a professor of medieval literature at a Mormon College in Utah, is “a solitary man stung by the flesh and gnawed by the spirit…a being of grandiose thoughts and microscopic cares, a blocked teacher, a reluctant martyr and a self-betrayed poet.” His lover, a well-to-do faculty wife, refuses to live with him and subsequently dies of an abortion. Saunders, in Toronto in 1933, pledges to ‘organize Vancouver’ for the Communists, mostly to impress a reluctant fiancee. His rides the freights and rents a $1-a-week flophouse atop the Hotel Universe on Powell Street under the pseudonym Paul Green. His migration from effete theorizing to political action, organizing men around Victory Square, takes him from the ‘univers-ity’ job to the real world of the Hotel Universe. Ultimately he returns to the security of teaching, pronouncing himself a fool, but no longer such an arrogant one. “The characters were from real life,” Birney once commented, “but the melodramatic ending is fiction. The Square was the prole forum, debating society and general bullshit centre.”

In 1933 Birney married fellow Trotskyite Sylvia Johnstone but she did not wish to relocate to Utah from Toronto, so she hastily returned to Toronto and their marriage was later annulled. In 1934, Birney received a Fellowship to the University of London, in England, to study Old and Middle English. He worked on a tramp freighter to reach London. He completed his doctoral thesis on Chaucer in England, researching at the British Museum and working for the Independent Labour Party. He went to Norway to interview Leon Trotsky, his political hero, in 1936. He also visited Berlin where he was taken into custody for failing to salute a Nazi parade.

More significantly, Birney met up with Esther Heiger, who had married Izrael Hieger. Born Esther Bull, of Russian-Jewish descent, she had served as his stenographer in England. The idealistic pair lived like gypsies in Dorset where Esther, recently divorced, helped him complete his 860-page thesis on Chaucer’s irony.

Pregnant, Esther came to Canada with Birney in 1936 and they lived briefly in Vancouver with Birney’s Presbyterian mother before the unwed couple moved to Toronto in 1938. Birney received his Ph.D and taught at the University or Toronto. He also edited Canadian Forum (1938-1940) prior to enlisting at age 38 for officer training in the Canadian army. Their only child, Bill, was born in 1941, but Birney was never a diligent father. Birney broke with Trotskyism and obtained a marriage certificate. “We got married for the sole purpose of giving the child legitimacy,” Esther Birney has recalled. “We both thought that marriage was a bourgeois institution having to do with property and possessions. We had a Marxist beginning and set out to live according to the Communist Manifesto. We believed you don’t possess people. For this reason, neither of us objected to affairs.”

Birney would have a prolific love life. As a professor, he encouraged gifted female students such as Phyllis Webb, Betty Lambert, Heather Spears, Marya Fiamengo and Rona Murray, and was not always able to limit his attentions to teaching. Throughout his adult life he was sexually active with countless women including Carlotta Makins, Margaret Crosland and Liz Cowley. A large percentage of his lovers remained intimate friends for decades. “I know full well that I brought genuine love to those women which is still with them and which they draw strength from to this day,” he once wrote.

In 1964, Birney brought home a 24-year-old art student, Ikuko Atsumi. The ‘open marriage’ that Birney wanted was no longer workable for Esther. “I’ve had a lot of crazy and perilous amorous adventures in my life,” he confided to Irving Layton, “95% of them unknown to anybody but the girl concerned–but this turmoil I’m in now is farther out than a Burrough’s novel…I’m going through the greatest, most beaufitul and, no kidding, the most passionate sexual experience of my life and I’ve no complaints about the past ones.”

Earle Birney left Esther, once again, but when Atsumi suddenly left for Japan, Esther allowed him back in 1966. So it went. In 1973, after his heart attack at age 69, Birney began cohabiting with a beautiful 24-year-old Cantonese graduate student, Wailin (Lily) Low. This became his greatest love affair. After Birney suffered a near-fatal fall while climbing a tree in July of 1975–at age 71–Wailin lovingly nursed him back to health and revitalized his spirits and his writing. Earle Birney and Esther Birney finally divorced in 1977 on the grounds of adultery, ending an unusual 37-year marriage. The divorce papers noted there had not been a sexual relationship between the married couple for 15 years. “What kind of de-sexed mouse was I–to burn & suffer & go on…Don’t torture me by telling me I am ‘always with you’ and that I am always your loved Esther. I’m not. I am your deserted, lied to, unloved Esther & I have been for years, since you came home after the war.”

During the war Birney passed three years in England, Belgium and Holland. By war’s end he was in England with diptheria, its attendant paralysis and the urge to write. He arrived in Canada on a hospital ship. In 1946, Birney became supervisor of the International Service of the Canadian Broadcasting Service based in Montreal and he began to edit The Canadian Poetry Magazine until June of 1948. In 1949, Birney published his military picaresque novel, Turvey, about Thomas Leadbeater Turvey who, like Birney, served as a personnel officer. Turvey is from Skookum Falls, B.C. He is first made a fireman until he drops a stove lid on his toe, then a waiter until he spills coffee down a Colonel’s neck. While supposedly guarding the Welland Canal, he is caught AWOL with a girl from Buffalo. He is eventually shipped to England, where his real troubles begin. A pirated version of the novel called The Kootenay Highlander was published in England in 1960.

Living in Toronto, with CBC connections, and having already won a Governor General’s Award for his first book David and Other Poems (1942) and a second one for his second poetry collection Now Is Time (1945), Birney set about getting to know the emerging literary and arts establishment of Canada. He developed relationships over the years with Lister Sinclair, E.J. Pratt, Louis Dudek, Lorne Pierce, Alan Crawley, Ralph Gustafson, Clyde Gilmour, Fred Cogswell, F.R. Scott, John Adaskin, Northrup Frye, Claude Bissell, Morley Callaghan, Robert Weaver, Jack Shadbolt, Anne Marriott, Roderick Haig-Brown, Bill McConnell, P.K. Page, Ethel Wilson, Paul Engle, Mirian Waddington, W. Kaye Lamb, Jack McClelland, Irving Layton, Stephen Vicinczey and Leonard Cohen, to name only a few.

In Vancouver, Birney befriended newcomers Malcolm Lowry and George Woodcock, and became a central personality in an unofficial writers’ colony that existed on Bowen Island, hosted by Einer Neilson. Birney was particularly helpful to George Woodcock in the early 1950s, getting him work as a college instructor in Washington State and at UBC despite Woodcock’s lack of a university diploma. After Lowry’s death, when North Vancouver wanted to make some amends for bulldozing the famous drunken author’s shack at Dollarton, Birney chose the site for Lowry’s Walk in Cates Park, nearby the latrines.

At UBC he jostled for power with Roy Daniells and tried to remain in the good graces of English department mentor Garnett Sedgewick, “the man of all men who had stood nearest in the role of father to me.” With Sedgewick’s help, Birney came to Vancouver in 1948 and taught medieval literature at UBC until 1965. While it’s fair to say Birney lobbied for the first-ever credit course in creative writing, and he stubbornly persisted in expanding the range of the writing course, he was not the sole founder of the UBC Creative Writing Department as is sometimes alleged. Daniells and others were also involved in the process. Nonetheless, Birney has been credited, by the likes of Andreas Schroeder, one of the leading faculty members of the department in later years, for having had the foresight to convincingly argue that any new creative writing agenda must not be operated under the aegis of the English department.

Ensconsed at UBC, Birney increasingly turned his hand to experimental poetry and verse play, resulting in one of his most enduring works, Trial of a City (1952), and Near False Creek Mouth (1964). Birney organized visits by Dylan Thomas, Theodore Roethke, Charles Olson and W.H. Auden, among others. He supported and encouraged countless writers and students such as Jack Hodgins, Tom Wayman, Daryl Duke, Norm Klenman, Heather Spears, George Bowering, Norman Newton, Frank Davey, George Johnston, Bill Galt, Lionel Kearns, Mary McAlpine, Daphne Marlatt, Ernie Perrault and Robert Harlow (who succeeded him as the second Head of the Creative Writing Department that began in 1963).

Birney’s influence as a teacher at UBC cannot be under-estimated. “He’d encouraged and taught me by the model he was,” says born-in-B.C. novelist Jack Hodgins, who became one of Canada’s foremost Creative Writing teachers, “if nothing else, just the fact that he existed caused me to want to be good.” While enthusiastic about a new generation of poets that included Leonard Cohen and bill bissett (whose non-UBC-oriented blewointmentpress he considered “the only genuinely experimental/contemporary mag in Canada”), Birney had severe reservations about the TISH movement engendered by American poetry professor Warren Tallman. “They introduced cultism in its extreme form,” Birney once wrote. “Anything written unlike what they were writing was dubbed not just inferior, but Anti-poetry. How the Puritan mind is reborn in every new movement.”

As one of the few Canadians in the UBC English faculty, he resisted and resented American cultural imperialism. “By god,” he said, “we’ve got to stand up and say we aren’t Yanks and won’t necessarily ever be Yanks.” Trying to remain hip, Birney mixed poetry with jazz, adopted contemporary clothing styles (Nehru jackets) and tried concrete poetry. He supported the likes of Michael Ondaatje, David Cronenberg, Austin Clarke, John Robert Colombo, Gwendolyn MacEwan, Joe Rosenblatt, John Newlove and Al Purdy. As an elderly man, he continued to travel around the world and particularly enjoyed skin diving. He spent time in France, Mexico, parts of Asia and South America, and Australia, writing numerous travel pieces and exporting Candian poetry, mostly his own, wherever he went. Birney left UBC to become the first Writer in Residence at the University of Toronto in 1965.

Birney’s vitality earned him the characterization of an old goat. Homophobic, self-righteous, vain, fond of fast cars, he once self-mockingly ended a poem with “too large an ego and too small a head / a sheep in company and a goat in bed.” His long-sufferering wife Esther once bitterly lamented, “What a mess most intellectuals make of their lives when their talents are real but small.” Birney equated creativity with virility. “I don’t want to equate art with sexual infidelity but in me there must be a connection somewhere. There is some deeply rooted thing in me that not only desires other women’s bodies, but that makes me spill over with very genuine feelings of tenderness and affection for more than one woman…I think loving is also a philosophy and kind of substitute art.” Wailin Low remained at Birney’s side after he suffered another near-fatal heart attack in 1987. She was steadfastly caring and protective of his reputation when Birney was a long-term patient at Toronto’s Queen Elizabeth with a disabling brain injury. Hospital. Initially supportive of a biography by Elspeth Cameron, she and Birney both resented the work. Cameron is disparaging in her assessments of Birney as a writer, suggesting his skills as a self-promoter and organizer were the foundation of his success.

Since Earle Birney died in Toronto on August 27, 1995, Wailin Low, now a judge in Ontario, has continued to control his literary affairs and has overseen a Earle Birney website, remaining true to their relationship. Remarkably, most of Birney’s books were out of print by 2005. Low subsequently concluded arrangements with Harbour Publishing to print a new collection of Birney’s selected poetry, including some love poems written in her honour, edited by Sam Solecki.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY:

David and other poems (Ryerson, 1942)

Now Is Time (Ryerson, 1945)

The Strait Of Anian: Selected Poems (Ryerson, 1948)

Turvey: A Military Picaresque (M&S 1949; rev. 1976; 1989)

Trial of A City, and Other Verse. (Ryerson, 1952)

Twentieth Century Canadian Poetry (Ryerson, 1953). Edited by Birney.

Down the Long Table (M&S, 1955)

The Kootenay Highlander (Four Square, 1960)

Ice, Cod, Bell or Stone (M&S, 1962)

Near False Creek Mouth (M&S, 1964)

Selected Poems, 1940-1966. (M&S, 1966)

Memory No Servant: Poems, 1947-1967 (New Books, 1968)

The Poems of Earle Birney. New Canadian Library (M&S, 1969)

Rag and Bone Shop (M&S, 1971)

The Bear on the Delhi Road (Chatto & Windus, 1973)

The Collected Poems of Earle Birney (M&S, 1975)

Down the Long Table. (M&S, 1975)

The Rugging And The Moving Times (Black Moss, 1976)

The Damnation of Vancouver (M&S, 1977)

Ghost in The Wheels: Selected Poems (M&S, 1977)

Fall By Fury & Other Makings (M&S, 1978)

Copernican Fix (ECW, 1985)

Last Makings (M&S, 1991)

One Muddy Hand (Harbour, 2006). Edited by Sam Solecki.

BOOKS ABOUT EARLE BIRNEY

Frank Davey, Earle Birney (1971)

Richard Robillard, Earle Birney (1971)

Bruce Nesbitt, ed. Earle Birney (1974)

Peter Aichinger, Earle Birney (1979)

Perspectives on Earle Birney (1981)

Elspeth Cameron, Early Birney: A Life (1994)

Nicholas Bradley, We Go Far Back in Time: The Letters of Earle Birney and Al Purdy, 1947-1984 (Harbour 2014). $39.95 978-1-55017-610-0

AWARDS

Governor General’s Award for David and Other Poems

Governor General’s Award for Now Is Time

Stephen Leacock Award for Humour for Turvey

Lorne Pierce Medal for Literature

Canada Council Medal

[BCBW 2014]

Quebec poet Bruce Taylor has been named the first recipient of the new Earle Birney Prize for Poetry worth $500, named after the founder of UBC Creative Writing Department. It’s awarded by UBC’s PRISM international magazine.

[BCBW 1997]

Esther Birney: obit (2006)

Esther Birney died on July 20, 2006. Having long managed a series of literary lectures at Brock House in Vancouver, she was remembered by UBC English professor Ronald Hatch: “Many members of the English Department gave talks at her series of literature lectures at Brock House, a series that is still ongoing. In speaking with other members of the department, I know that she is remembered with great affection. People still speak of Esther’s warm greeting and her vibrant introductions. Especially appreciated were the stimulating conversations after the lecture over lunch. Amongst the English Department there is also the memory of her fierceness in debate, her refusal to accept half-truths. There is more than one lecturer who recalls being pushed to sharpen a particular argument, and in truth it was a strong speaker who could stand up to the queries of Esther Birney, especially when Hilda Thomas and Peter Remnant joined her. I was particularly fond of having her talk about her own responses to culture, for they were never half-hearted. There are still those who may recall what she had to say about Benjamin Britten’s ‘dissonant’ Peter Grimes on the occasion when I came to speak about George Crabbe, who wrote the original poem. At an age when many people are settling for short books, Esther embarked on the complete Proust, and remarked how much she enjoyed being involved in the vastness of Proust’s design. It was refreshing to hear her talk about her political activism, her Trotskyism in the 1930s, when she and Earle lived in a tiny caravan on the Dorset coast, in Hardy country. Her struggle for social justice never left her. Most of all, however, I remember a woman overflowing with life, an example to all of us.”

One Muddy Hand: Early Birney (Harbour $18.95)

Review by Hannah Main-van

Earle Birney’s famous poem about the death of a hiking companion, “David,” had been published twenty years before I first heard it. I can still recall the voice of Mr. Burt, my Grade 12 English teacher, reading it aloud and reading it well.

“That day we chanced on the skull and the splayed white ribs

Of a mountain goat underneath a cliff-face, caught

On a rock. Around were the silken feathers of hawks.

And that was the first time I knew that a goat could slip.”

It remains visceral, the shock of that poem; its powerful rhythm and wording as well as the unforgettable narrative about a mountain climbing fatality. It is one of the few poems in the Canadian canon that most readers of this column might recognize.

Naturally “David” has been included in One Muddy Hand (Harbour $18.95), the only Birney collection currently in print, but this is a surprising book. Along with David, one might expect mostly worn-out or sentimental work from an academic born more than a hundred years ago but his modernity and energy astound. There are poems with ecological insight, others with a passion for indigenous cultures, as well as sensitive and delicate love poems. Editor Sam Solecki has collected an amazing variety of work. While starting out as a traditional formalist, heavy on Anglo-Saxon rhythms, Birney, an avid outdoorsman and hiker, continually experimented with form, shape and voice. The work of Birney’s friend and fellow poet Al Purdy (also collected by Sam Solecki) is the nearest in comparison. Both were unmistakably Canadian though that’s hard to define how and why. Both were also peripatetic travelers, restless even. Poems by Birney flowed from and about Mexico, Thailand, Istanbul, Japan and Peru. Then he’s in Australia or London or writing in a tavern by the Hellespont.

Birney never wrote the same poem twice. In “The Speech of a Salish Chief,” taken from The Damnation of Vancouver, Birney wrote of Indian baskets and the destruction of First Nations culture:

“Red roots and yellow weeds entwined themselves

Within our women’s hands, coiled to those baskets darting

With the grey wave’s pattern, or the wings

Of dragonflies, you keep in your great cities now

Within glass boxes. Now they are art, white man’s taboo

But once they held sweet water…”

Birney’s last great love was a much younger woman named Wailan Low who cared for him later when he was ill and disabled. The sequence of love poems written to and for her, many of them on her birthdays, are so intimate it feels like a blundering intrusion to read them. No doubt their spring/winter relationship caused a stir but to read these poems now is to sense them as a memorial of surprise and gratitude. How genuine his love for her was; one hesitates to use the word “sweet” because it’s been so over-used and ruined by cynics.

The love poems are unaffected and unpretentious; short and deceptively slight:

“the magic flows

in the wind that bends

the waterlily’s face

to the lips of the wrinkling lake.”

With wry allusions to their difference in age, Birney repeatedly sets her free, to go on after his death:

“to warm another

with the same love

you shone steadfast on me

If sometime my shadow

flits over the embers

it’s just to bless.”

The volume concludes with about fifteen pages of Birney’s prose which demonstrate his humour and the contemporary nature of his poetics. He writes, “There’s a curious peace that comes in the intensity of practicing one’s metier, an absorption that annihilates time and place.” In 1966, when most Canadian readers had not yet noticed Marshall McLuhan, Birney wrote, “Literature is all the more alive today because it is changing so rapidly. In fact it’s adjusting to the possibility that the printed page is no longer the chief disseminator of ideas.” The prose section includes a long piece on the composition of David, the poem which ends unforgettably like this:

“I said that he fell straight to the ice where they found him,

And none but the sun and incurious clouds have lingered

Around the marks of that day on the ledge of the Finger,

That day, the last of my youth and the last of our mountains.”

Despite more than five decades of literary activity, Earle Birney, who died eleven years ago while in his nineties, has been fading in notoriety.

Thousands of talented writers are coming out of Creative Writing programs these days, not to mention many more who are skilled poetry readers and book buyers, yet how many know it was Birney, along with UBC professor Roy Daniells, who started the first Writing Workshop in Canada, forty years ago, at UBC? As it matured into the country’s first Creative Writing Department, Birney was its first head. Since then his influence on writers in this province, and in this country, cannot be over-stated.

1-555017-370-7

[BCBW 2006]

Origins of Creative Writing at UBC: excerpt by George McWhirter

In a piece called Origins & Peregrinations, a former head of UBC Creative Writing, George McWhirter has attempted to set the record straight.

Preface

The debate regarding the appropriate academic place of Creative Writing within North American universities is an old one and has intensified in recent years. Is the live process and actual production of literature fully an equal value partner to the study of literature through commentary and the critical analysis of process? At the invitation of UFV Research Review, George McWhirter, former Department Head of the Creative Writing program at UBC and the past inaugural Poet Laureate of the City of Vancouver, examines this critical literary and educational issue. In doing so, he relates much regarding the development and evolution of UBC’s pioneering Canadian program in Creative Writing, as well as his from his own experience in preparing young writers for a professional career.

Origins & Peregrinations

Why did Earle Birney split from Creative Writing at UBC after he had forced Creative Writing to split from the English Department and became an independent department? Apart from being exhausted by the process of separation and being fed up with UBC — the English Department approach follows academic method, and Creative Writing, the professional — the simple answer is that Earle retired. He got in a former student and Director of CBC Vancouver, Bob Harlow, to be first Head.

Later, in the 1980s when Earle was made a UBC honorary doctor, there was a Creative Writing founders’ fight — it was resolved by R.W. Will, the Dean of Arts, who declared Earle the founding force and father, but Bob as the first Head, which he was. It was Jake Zilber who did major committee work on the movement of the proposal for a Creative Writing Department through the Faculty of Arts and various governing bodies.

I’ll go over some of the ironies about the split, which is endemic to the difference between the Creative Writing process and the English Literature studies approach. The English Department approach follows academic method, and Creative Writing, the professional; hence the Creative Writing degree is a MFA and is terminal, without a Ph.D dimension at UBC, because at that point it would also get into the study of the writing process as well as the practice. However, other institutions now do offer Ph.Ds in Creative Writing.

The split between the academic learning about literature and the creative writing professional’s approach to learning by doing recurred in the late seventies. I proposed a graduate course in Editing and Managing a Literary Magazine that would turn the production of PRISM International with graduate students.

Leave a Reply