Race for the news

The arrival of the telegraph at Cape Race, Nfld. in the 1850s transformed journalism and global news delivery.

August 28th, 2025

Theresa O’Leary, award-winning CBC journalist, playwright and filmmaker.

“[Daniel] Craig’s greatest legacy may be that he introduced journalistic standards: he wanted fact-based, objective reporting.”—reviewer, Mark Forsythe on a news gatherer who benefitted from telegram technology.

Review by Mark Forsythe

For better or worse, our wired world can be traced to the pulse of the telegraph. Samuel Morse’s first message tapped out between Washington, D.C. and Baltimore read: “What Hath God wrought.” That was 1844, and soon a web of land-based networks emerged and a transatlantic cable eventually connected the Old World to the New. This was cause for celebration from New York to London, with messages exchanged between Queen Victoria and President Buchanan.

Information had become instantaneous—transmitted in minutes, not weeks. Time and distance collapsed. The advancement of journalism can also be traced to this breakthrough, the most important advance since the Gutenberg press. The telegraph led to newswire services, driven by an intense competition to be first to get the story to newspaper readers. This sparked imaginative strategies involving carrier pigeons, the pony express, and men in rowboats retrieving news canisters tossed overboard by passing ships off Cape Race, Newfoundland. This elaborate relay race delivered news to the nearest telegraph station for transmission to the papers in New York City, Boston, Montreal and elsewhere.

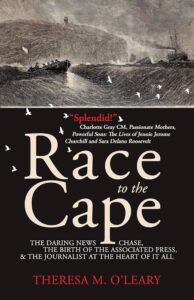

Race to the Cape: The Daring News Chase, the Birth of the Associated Press, and the Journalist at the Heart of It All (Ingenium Books, $29.99) by Theresa O’Leary is an engrossing account of how this technical revolution altered the nature of news gathering, pinpointing the figures who made it happen. The former CBC Radio National News reporter began her career in B.C., has won international awards for her journalism, and continues to live here.

Race to the Cape: The Daring News Chase, the Birth of the Associated Press, and the Journalist at the Heart of It All (Ingenium Books, $29.99) by Theresa O’Leary is an engrossing account of how this technical revolution altered the nature of news gathering, pinpointing the figures who made it happen. The former CBC Radio National News reporter began her career in B.C., has won international awards for her journalism, and continues to live here.

O’Leary’s family roots reach deep into the southern tip of the Avalon Peninsula where Irish ancestors settled at Portugal Cove South in the 1700s. The wind and cold could be so bitter that locals lamented, “It cut the face off ya.” They were there in the 1850s when a lighthouse and telegraph hut were built at Cape Race, just a dozen miles away (19 km). Her great-aunt Kitty worked on the telegraph, and O’Leary grew up hearing stories—one claiming Kitty was at Cape Race the night the Titanic wired its frantic message.

Great Aunt Kitty and husband Frank Leahy at Cape Boyle

Cape Race was the first landfall for ships crossing the Atlantic from Europe, one third closer than the rest of the eastern seaboard. “Rugged and stark, Cape Race was all sharp cliff edges and open sky…the jagged shoreline of reefs and shoals—a foggy mirage—sat waiting for ships to wreck.” We learn these treacherous waters also became a graveyard for hundreds, including victims from the Anglo-Saxon, the worst disaster in Newfoundland history.

In the mid-1800s there was constant demand for news from Europe, especially the London markets. Businessmen wanted the price of coffee, corn, bacon and cotton, which dictated decisions at home. Establishment newspapers of the day competed for this information, catering to specific audiences—often political or business oriented. They were mostly driven by opinion rather than impartial news.

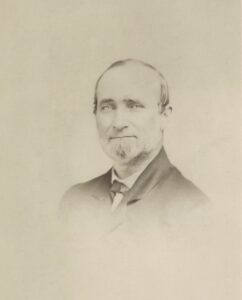

Daniel H. Craig. 1881. Central character in Race to the Cape.

In the 1830s a young news gatherer named Daniel H. Craig was working at The Sun in Baltimore, one of the penny papers beginning to flourish and challenge the establishment papers. Its focus was on crime, courts, fires and relevant information geared to “the common good.” He sent headlines to his editors after stuffing them inside tiny tubes attached to carrier pigeons. Later he worked in Boston, chasing news from incoming transatlantic ships, using a rowboat and more pigeons to scoop the competition. Craig developed a reputation for being unbeatable.

As telegraph networks expanded, he moved to Halifax where he gathered information from ships, sending carrier pigeons to his wife Helena, who quickly telegraphed the news to clients in New York City. By 1851 he was in New York City serving as managing editor of the New York Associated Press, a newswire funded by the major newspapers looking to cut costs (which became AP wire service). Under his leadership, wherever the telegraph went, NYAP followed, hiring well paid local reporters. After collaborating with investor Cyrus W. Field—the man behind the first successful transatlantic cable system—Craig gained exclusive access to the telegraph. He established another version of the rowboat news at Cape Race where his men snagged news canisters from the ocean. The race was on, and he boasted: “Nearly all the European News will be landed at Cape Race.”

Craig’s greatest legacy may be that he introduced journalistic standards: he wanted fact-based, objective reporting. This became critical to the evolution of a profession that became a crucial element of democracy. With today’s proliferation of opinion masquerading as journalism, social media silos and a staggering loss of local news sources, it’s important to be reminded of the value and power of public-minded journalism and the vision required to attain it. As a work of creative non-fiction, O’Leary asks readers to temporarily suspend disbelief for some imagined conversations between these historical figures. That said, Race to the Cape would make a fine introduction to any journalism class. 9781990688577

Mark Forsythe is a former host with CBC Radio.

Sounds like an outstanding book!