Go west young man

Dennis E. Bolen’s coming-of-age story of a 15-year-old driving from the prairies to BC in 1967.

September 04th, 2025

Dennis E. Bolen is the author of 9 books of fiction and one poetry collection.

“[The story] is a historical artefact centred on a pivotal year in Canadian history and in a broader transformative decade, it’s a nostalgic reminder of just how much people—especially young people—have changed since the Post-War years.”—reviewer, Peter Babiak.

Review by Peter Babiak

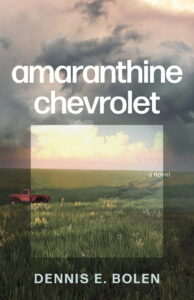

No archetype connects the literary world to our day-to-day real world better than the road trip. It’s such an enduring story-telling mechanism because in literature and in life the best part is the journey not the destination. That’s why road-trips define so many classics such as the Odyssey, Canterbury Tales and The Grapes of Wrath. And now Victoria writer Dennis Bolen has published Amaranthine Chevrolet (Dundurn $25.99), an entertaining and exceptionally lyrical coming-of-age novel about Robin Wallenco, a fifteen-year-old who, in the summer of 1967, illegally drives an unlawfully-obtained 1942 Chevy pick-up from Saskatchewan to British Columbia.

Bolen’s ambient prose offers readers what’s important in all memorable quest narratives. Episodic events with their own conflicts and resolutions, here framed by the expressive geography of western Canada. Because Robin needs to steer clear of authority figures, his trek involves “teamstering” the ‘42 over prairie ruts and cross-field tracks “away from the main across rough pasture of cow-pie and sedge” and then, as fields buckle into foothills and then mountains, on back country trails and forestry service roads. “The going was slow to the point of disappointment,” the narrator tells us early on, and that Robin “felt like he was the last boy on earth,” but nowhere is Bolen’s storytelling less than captivating. “Everywhere,” as we learn when Robin detours to a Princeton auto-wreck yard, “the suggestion of painful mortality was leavened by yawning invitations to be fascinated.”

Bolen’s ambient prose offers readers what’s important in all memorable quest narratives. Episodic events with their own conflicts and resolutions, here framed by the expressive geography of western Canada. Because Robin needs to steer clear of authority figures, his trek involves “teamstering” the ‘42 over prairie ruts and cross-field tracks “away from the main across rough pasture of cow-pie and sedge” and then, as fields buckle into foothills and then mountains, on back country trails and forestry service roads. “The going was slow to the point of disappointment,” the narrator tells us early on, and that Robin “felt like he was the last boy on earth,” but nowhere is Bolen’s storytelling less than captivating. “Everywhere,” as we learn when Robin detours to a Princeton auto-wreck yard, “the suggestion of painful mortality was leavened by yawning invitations to be fascinated.”

There’s a cast of archetypal characters, too: a wise Cree war veteran, sixties flower children, a BC “weed” farmer, a seductive young woman, a dying young woman—all of whom seem personifications of their different settings. Orville, for example, is a salt of the earth Saskatchewan man who devotes “a heavily industrial half-day” helping Robin fix the Chevy after the boy’s first mishap; the man also delivers the novel’s central theme: “Kid… you’re the envy of every decent man. The thought of just picking up and driving out in your personal vehicle for parts little known. No particular schedule. Fate dictating every single day. Even for a little while it would suit one man or another at some part of his life.” And then there’s Aldis, a seventeen-year-old on a hippy excursion to Expo in Montreal who delivers herself to the back of Robin’s truck and into his sleeping bag one night at an “impromptu campsite,” where the boy is rendered speechless by “the art of her.”

There’s the mission itself, which keeps Robin—who drives the Chevy mostly alone—determined to make his way west, though the object of his quest isn’t as important as the people and places he experiences along the way. Nor does the reason for his trip to BC become clear until he gets to his destination “out on the west edge” of Vancouver Island. This is where we learn that Robin wants to present the near-mythical truck to his dad, an estranged man who, having abandoned his wife, sons, parental integrity and much of his hope, lives in a trailer by the beach in Tofino.

What Bolen does remarkably well in Amaranthine Chevrolet is balance the need for an entertaining story with an admirable concern for the linguistic technique of his craft. He’s a writer who typifies Annie Dilliard’s claim that, just as a painter is a painter if they like the smell of paint, a writer is a writer if they “like sentences.” Here, for instance, is his narrator’s description of Robin leaving an abandoned church in a Saskatchewan field where a fellow outlaw helps him by ringing the church bells to divert the RCMP they’ve spotted in the distance: “The peal began before he could hit the starter and as the heretofore comforting silence vanished inside the ardent tintinnabulation, the vibration made him strangely know that others existed on this freshening morning.” The exalted language marks a classic epiphany, but Bolen doesn’t do the interminable inwardness that sometimes accompanies such moments. And here is an auto-wrecker in Princeton getting profound about the “rolling artifact” Robin drove into his yard looking for a replacement oil pan after bottoming out on a forestry road between the Kootenays and Kelowna: “But there’s an historical-philosophical element too. They are the form-and-function artistic manifestation of a singular industrial heritage.”

Far from being unnecessary figurative detours, sentences like these are little engines that produce poetic insights of an entirely prosaic nature; and they come from the same pared-down, nose-to-the-grindstone realism we find in Ernest Hemingway, Morley Callaghan and Cormac McCarthy. Bolen’s protagonist has none of Holden Caulfield’s urbane cynicism and though, as a fifteen-year-old kid living in 1967, his protagonist possesses a practical intellect that would make most adult readers today feel like kids, this isn’t the precocious mind of a Ponyboy Curtis, either. “Being of the practical land himself and thus resistant to metaphysical sentiment,” the narrator says of Robin, “he did not ponder hard.” Who has time to ponder when they’re an illegal driver covertly navigating a ‘42 Chevy from Saskatchewan to British Columbia?

Amaranthine Chevrolet is a compelling novel for many reasons. It’s a historical artefact centred on a pivotal year in Canadian history and in a broader transformative decade, it’s a nostalgic reminder of just how much people—especially young people—have changed since the Post-War years, and it offers an alternative perspective on a 1500-kilometre drive across Western Canada that most of us will only do from the safety of the Trans-Canada Highway. But this novel needs to be read for the conscientious language craft—the novel diction, periodically unexpected syntax or oddly positioned prepositional phrases, a near absence of punctuation besides periods (I circled two commas on opposing pages because they’re so rare), the complete absence of quotation marks—Bolen devotes to this fun and engaging novel. 9781459754775

Peter Babiak is an author and instructor in Langara College’s English Department.

Leave a Reply