From working-class kid to premier

Raised by a single mom, John Horgan was held in high affection during his time in office.

December 18th, 2025

John Horgan served as the 36th premier of British Columbia.

“[After getting elected in 2017, Horgan’s NDP] got busy: no more Medical Services Plan premiums, improved disability assistance rates, tuition fees waived for adult education and ESL, free post-secondary education for 18-year-olds coming out of foster care, Port Mann Bridge tolls ended. And the NDP increased the minimum wage.”

Review by Trevor Carolan

John Horgan, BC’s 36th Premier, passed away in 2024 after leading the province for five years and resigning in 2022. Few provincial leaders in living memory earned the level of public affection Horgan enjoyed, a tribute to his stalwart administration during the global Covid epidemic. While others faced economic, social or environmental challenges, none as premier ever confronted an existential crisis of that magnitude. His legacy is engraved at the heart of our definition of genuine public service.

We knew little of his personal story. Horgan squeaked into the premier’s office through an alliance with the Green Party in 2017, ending sixteen years of Liberal government that was tarnished by the “Casino Gate” scandal (when alleged foreign money was laundered through gambling and later invested in BC real estate) … or when, as The Province newspaper reported, “Metro Vancouver housing prices soared beyond the reach of non-millionaires.”

Rod Mickleburgh

John Horgan: In His Own Words by John Horgan with Rod Mickleburgh (Harbour, $38.95) is filled with remembrance. Following Horgan’s resignation as premier, an event as unexpected and free of drama as Bill Bennett’s departure in 1986, Horgan—a two-time cancer survivor—recorded a series of interview conversations with labour journalist Rod Mickleburgh addressing his life and the history of his long political voyage. They met at Royal Rhodes University in Victoria in August 2023 and their sessions ran several days. They talked again the following November. More interviews followed via Zoom sessions in spring, 2024 after Horgan had been appointed Canada’s ambassador to Germany. But that June, Horgan was detected with thyroid cancer—his third round with the disease. Mickleburgh’s introduction relates that with Horgan sitting up in his Berlin hospital bed, logged four final sessions in late-August. Horgan died in November.

Those interviews shape In His Own Words, a deep-dive memoir and autobiography from a political leader broadly experienced in governing. Horgan knew hard-times growing up and if salty language isn’t in your wheel-house, especially in the early chapters, be advised.

BC’s first NDP premier to earn re-election recalls how his path to the premier’s office came after years as an NDP staffer, in Ottawa and Victoria. He attended Trent University in Peterborough after learning of it in Ocean Falls, the pulp mill town where he migrated after a working-class upbringing in Saanich. The mill’s solid union wages enabled him to study social work. At Trent, he heard Canada’s beloved social justice hero, Tommy Douglas speak. From then on, Horgan intimates, he knew who he was and that what he believed in was worth fighting for.

His father, he says, was a drunk. An Irish scrapper and sports fan who made truck deliveries around Chinatown. He died while Horgan was an infant, leaving the load of raising four kids to his wife, Alice. “She did everything pretty much by herself,” Horgan explains.

Horgan had a passion for lacrosse. He could play and became, he says, “the guy everyone wanted on their team.” Horgan dreamed of joining Victoria’s renowned Shamrocks, yet never made the senior squad. Yet it was during this time he grasped, “team sports were where you learned that everyone’s role was important.”

By grade 8, Horgan concedes he “was heading into the ditch.” He was troubled and credits Jack Lusk, his high-school basketball coach for bringing him around. He finished high school, the only one of his siblings to manage that. His mother returned to school, learned to drive and secured a CUPE job in local government with a pension. While not a religious family, “the basic decency of Christianity permeated our existence,” Horgan recalls. Along the way he befriended Bruce Hutchinson, the renowned political journalist. They’d spend hours together by the stove, “talking about politics, past and present.”

At Trent, Horgan met his wife Ellie, a biologist who became his rock and accompanied him to Australia where he earned his Master’s in History. Five years in Ottawa followed, where Horgan worked in public policy development for the NDP. The narrative spices up when he recalls his favourite MPs. This is a book that names names—those who helped, and those who helped themselves.

In 1991, the Horgan family settled in Victoria’s Langford district. Horgan worked in various capacities for three premiers—Mike Harcourt, Glen Clark and Dan Miller. His strength was fixing problems—he got things done. Horgan speaks candidly about these former bosses and of Ujjal Dosanjh whose premier’s term ended the NDP’s almost 10-year run in office. Significantly, Horgan was drawn to natural resource and energy development issues. In 1999, he moved sideways into the Columbia Power Corporation, a Crown operation responsible for putting “the final elements of the Columbia River Treaty into place.” Involving flood control, purchasing and repowering existing dams from Cominco, job creation for the Kootenays and revenue generation from selling energy to the US, Horgan confirms that, “It all added to a $500 million deal.”

Dan Miller, the short-term premier from Prince Rupert, hired Horgan as his Chief of Staff just as climate change began making government agendas. Horgan understood that energy and emissions action was about to boom and could talk to environmentalists and big labour alike. But the NDP was dethroned in 2001; Horgan considered his future from the sidelines.

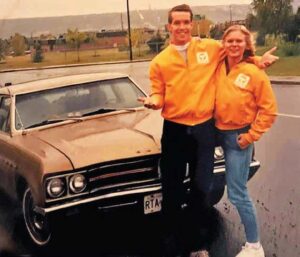

In 1986, just back from Australia, John and Eliie bought a 1967 Buick from friends in Victoria for $17.50 and drove it across Canada, looking for suitable employment. Eventually, both found work in Ottawa.

When Gordon Campbell’s Liberals awarded a ferry-building contract to Germany, Horgan howled at the news. The drummer in his son’s garage rock band overheard and asked, “Well, what are you going to do about it?” Horgan responded by getting elected as MLA in the next election, joining leader Carole James’ official Opposition. For 12 years he polished his public speaking and media skills, critiquing Liberal premiers Campbell and Christy Clark. When Clark demolished Adrian Dix in the 2013 election, Horgan says it was “one of the worst campaigns I’ve ever seen.”

Known as an economic pragmatist, Horgan was approached to join the Liberals who needed an Island voice, but declined to cross over. He saw that Clark had out-strategized the NDP and didn’t forget.

By 2014, Horgan was leader of BC’s NDP. The party was stone-broke and had “internal divisions.” He tread water, built alliances with unions and the Indigenous community, and gradually pulled things into cohesion. Significantly, Horgan championed the UN’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) for which he is still warmly remembered, and he includes a chapter of sincerity and insight into Indigenous issues and reconciliation. He also developed a reputation for his temper. He and Clark did not get on—“not at all,” Horgan emphasizes.

With his party still struggling, Horgan brought in Bob Dewar, a seasoned Manitoba campaigner, as Chief of Staff. Dewar brought the mojo Horgan needed and “the sinking stopped.” Then came the Big One. In 2017, Horgan pulled off the unthinkable after forging an understanding with Dr. Andrew Weaver, leader of BC’s Greens. With their combined seats, they narrowly toppled Christy Clark, despite her pleas for a second, snap election that Lieutenant-Governor Judith Guichon declined. Horgan’s explanation of the agreement with Weaver is fascinating reading. Both made economic and ecological compromises that benefitted the province.

Selfie snapped by John Horgan with Ellie as they smell the lilacs a few minutes from their ambassador’s residence in Berlin.

Horgan’s party inherited a budget surplus from the Liberals. The NDP got busy: no more Medical Services Plan premiums, improved disability assistance rates, tuition fees waived for adult education and ESL, free post-secondary education for 18-year-olds coming out of foster care, Port Mann Bridge tolls ended. The NDP increased the minimum wage. Carole James in Finance added a new tax bracket for those earning over $250,000, as well as a speculation and vacancy tax on empty homes. They balanced the budget and BC earned Canada’s highest credit rating. Horgan delivered for the people and didn’t mind sharing the applause around, regardless of affiliation.

He admits “the transition from activist to administrator” is challenging. But it was the anti-Old Growth logging protests at Fairy Creek and the Site C dam decision in the Peace River country that earned him the wrath of eco-activists. On the books for 40 years and kick-started by the Liberals, the Site C infrastructure project faced skyrocketing costs and geotechnical issues. Yet, “even if getting there has been one of the province’s most challenging public policy questions,” Horgan could see its enormous value “in an energy-constrained marketplace.” He moved it forward. His chapter on working with the Greens on this and LNG issues explores the most complex ethical and economic questions he encountered in political life. Of his controversial commitments to “working forests,” hydroelectric power and developing LNG as a clean energy source —a $40 billion private sector investment—he explains his higher responsibility to “[meet] the needs of five million people,” not just the dissenters.

When Covid hit in 2020, Horgan’s government lead a bewildered public through the shock. His deputies on the file, Dr. Bonnie Henry and Adrian Dix, got BC past the worst. Who can forget their nightly updates? Ironically, the Greens’ support grew shaky; Andrew Weaver began sitting as an independent. Horgan’s decision to call a snap election after only three years caused grief and he speaks compellingly to this.

Maximum pressure came in 2021: extreme temperatures, a “heat dome” and “atmospheric rivers,” vast wildfires including the Lytton conflagration, flooding, and pipeline decisions—it was a fateful time. And Horgan now had throat cancer.

Horgan maintains he was already “becoming a grumpy happy warrior;” however, a badly thought-out decision proposing a long public closure of the Royal BC Museum proved the tipping point. He realized that he was “not reading the room right on something [he was] passionate about.” Mindfully, he apologized and decided he was done.

In his afterword, Mickleburgh concludes this valuable book with an emotional grace-note. Horgan’s son Evan asked him during a final hospital visit in Victoria what he would want Evan to say about him after he died. Horgan responded simply, “Just tell everyone I did my level best.”

John Horgan died the next day. 9781998526260

Trevor Carolan writes from North Vancouver where he served as Municipal Councillor.

Leave a Reply