Cranbrook Public Library’s centennial

From a small reading room in 1906, Cranbrook rented space for its first official public library in 1925. Here we excerpt a new book about the library’s first one hundred years.

November 19th, 2025

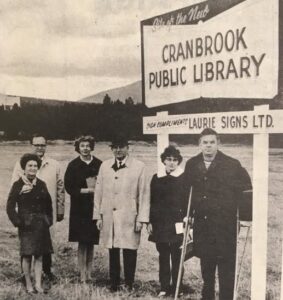

Signs of a new library: Trustees and an official stand in front of a sign announcing plans for a new purpose-built Cranbrook Public Library, circa 1969/70.

“In 1906, 100 books were deposited into a second-floor room in the Watts Block, right above Mighton’s Tobacco Store (currently Hush Home Furnishing on Baker Street). It was simply called the “Free Reading Room.”

EXCERPT

Chapter One: Love & Theft

Cranbrook is made up of many stories; or one story, with many fragments, many points of time, some unexpected, most inevitable. You can find the beauty of its wilderness in the 1888 Norwegian book Tre i Kanada, af forfatterne til ‘Tre i Norge, its authors speechless at the sky lighting up the horizon “no words of ours could attempt to describe [it.]” They soon encountered “the dim outline of a confused huddle of buildings; a door thrown open and a huge cheery English fireplace and a welcome instead of an evil-smelling, talc-windowed American stove and a register book, and we were safe in Cranbrook.”

That’s as good a description as any, with the authors concluding Cranbrook to be “the most go-ahead place we have seen in this country.” What a difference a decade would make, when the Canadian Pacific Railway arrived in 1898. That company would transform that huddle of buildings into “the centre of fine lumber and mining district, with well stocked stores meeting every requirement.” Empty lots are “in demand” and the provincial government “has important offices here.” The railway opened up the place as it never had before; exerting a gravitational pull so unavoidable Cranbrook would incorporate as a city in 1905.

The railway also brought people who could read and write. In 1901, a quarter of Cranbrook’s residents were illiterate; by 1920, that was down to 10 percent. Evidence of this was the three separate newspapers being published at the time, as well as Canada Customs bemoaning the fact that “the large Anglo-Saxon population” had “considerable imports by parcel post.” Some of this was no doubt reading material, but for the majority of Cranbrook residents book-ownership would be limited. As pioneer Susan Allison would note in her memories of the area, “[of] books—we had none.)”

Provincial reading room, 1906.

The still young provincial government, well aware of this unmet need, sought to remedy this.

In 1906 they deposited 100 books into a second floor room in the Watts Block, right above Mighton’s Tobacco Store (currently Hush Home Furnishing on Baker St.). Calling it the ‘Free Reading Room,’ their press office wrote “Any resident of Cranbrook or vicinity is entitled to the loan of these books as long as such person complies with the rules, having first signed the agreement, which will be presented by the librarian.” This continued with a list of rules, stating “books must be handled with care; two volumes may be drawn by each reader and retained for two weeks. The fine of five cents shall be paid for each book kept over time, and no books shall be lent to any to whom books or an unpaid fine or fines are charged.” There was also more instructions about reserving an item, as well as a list of all the newspapers and magazines available. The notable part is the reading room “is not run by, nor in the interest of any church, party, or clique. Everybody welcome.”

This is pure fantasy. While the government did send books out to smaller communities across the province, sending out trained librarians with them is wishful thinking; logistically and financially impossible at the time. Although the Fernie Operatic Company staged the comedy Our Boys’ as a fund raiser for the “Cranbrook Free Reading Room and Public Library,” this was just to build shelves. Which weren’t needed anyway, as all the books were quickly stolen.

Which was a horror to the editor of the Cranbrook Prospector, who went looking for them, albeit 5 years later. After berating Cranbrook’s residents, he accused the town’s service organizations—who had free use of the room for their meetings–writing “one and then another has looked these books over. Many found them so interesting they took them home and put them away among their own books and forgot.” After obtaining a list of the original books that the province had supplied, the editor listed each one in the November 11th, 1911 edition. This is followed by an appeal to the now chastened citizens of Cranbrook to “look over their bookcases and on shelves” and return them to the newspaper’s address. “Perhaps,” Stasi-like, “it is the friend living next door who has one of the missing books.”

Only one of the missing books was ever returned, Herbert Elliot Hamblen’s 1900 literary masterpiece The Return of Bucko Mate.

Subscription libraries also begin to appear at this time. The Anglican Christ Church boasted a small collection of books, “open to all on equal terms at a nominal fee of 50 cents for six months.” Beattie & Atchison Drug Store hung “Join Our Lending Library” sign, suspiciously promising “new books and new magazines every day.” Although it will cost one 75 cents to join, and another 20 cents for each title borrowed, do not worry as these “bargains” will “pay you.”

For those who couldn’t afford to subscribe, the “Travelling Men’s Association have installed a library of 100 volumes of choice literature in the office of the Cranbrook Hotel.” It is almost poetic that Cranbrook’s first building, situated close to the railway, offered this large selection of titles at no charge. One didn’t have to be a guest to borrow a book, but no doubt one could not leave the building with one. Even more poetic is that shelf still exists, having only left the Cranbrook Hotel recently into private hands.

The Railway’s YMCA building also had a reading room—originally for railway employees—one they hoped would turn into a “public library idea.” Shelved were built, and they put out a call to the public to donate “good standard works,” guessing those interested knew what both “good” and “standard” works were.”

Another public library was proposed in 1921; this one piggybacking on a soldier’s memorial, the lack of one being a sore spot to many. “Instantly,” the proposal read, “there will be a number heard to say they don’t believe a library is the best form for a memorial to take.” That number was correct.

1921 also saw Ms. Fok Rui Lian, a member of Cranbrook’s growing Chinese community, donate funds for the Chee Kung Tong Reading Room. Also known as the Chinese Freemasons Society (unrelated to the Masonic Order) the Chee Kung Tong library boasted hundreds of books and magazines, all aimed at helping Chinese newcomers to Cranbrook.

At a city council meeting the following year, the Rotary Club strongly suggested the building of a city park, including a swimming pool to stop children from “bathing in the creek,” as well as architectural plans for a “bandstand, and later on a building for a public library.” The park was built; the library was not.

This town without books was so distressing to one visitor in 1912, that he wrote a letter to the Cranbrook Herald feeling “something is wrong with the people” here. “In all my travels over British Columbia…Cranbrook is the only city of importance which I have visited in which there is no public library.” This anonymous author went on to inform whoever kept reading that “there are many that do not care to hang around hotels,” and many “ who are not so fortunate as to hold membership in some club in which literature is provided.”

A similar letter from “Booklover,” had appeared the year before: “As one who has knocked about the western country a great…I have noted with extreme regret the absence of any public library.” Should Cranbrook get a library, Booklover appointed himself arbiter of what Cranbrook should and should not be reading “My idea would not be to secure a large collection of modern novels for this library, but rather a collection, limited, to say, a few hundred choice masterpieces and the cream of the world’s best literature.” This library should also be “well conducted,” even though “lumberjacks and railroad men, as a class, may not be regarded as book lovers.”

Cranbrook Public Library anniversary book jacket cover.

1914 saw a similar letter from “Bookworm,” hoping the “spirited and right-minded members of the community” would establish a library. “I need not here go in to the question of why the establishment of one IS a necessity! No one will deny it.” What is the hold up, when “there exists no town in B.C., with half this city’s population, and I am sure, with one quarter its average intelligence and erudition, that does not boast this necessary adjunct to its public buildings.”

That is a lot of backhanded comments, and very little truth. The only towns in BC that could “boast this necessary adjunct” were Vancouver, Victoria, and New Westminster; geographically far away and none of those cities had what we would think of as a true public library.

Which is what exactly?

The First Digression

In medieval times (and today), the term “library” was defined as “simply a collection of books.” Medieval scholars took this further, defining it as “a collection of books acquired and arranged for the purposes of study and the pursuit of knowledge.” Both of these still fit into our modern concept of libraries, but what about the noun “public library.” This becomes much more problematic.

The ancient libraries of Greece, Egypt, and Rome, all called their libraries “public,” as did all later ones appearing in Europe. Even universities had “public” libraries attached to them; Oxford’s heralded librarian Thomas Bodley’s “publick” library is one prime example. All of these however were just rich people’s play things; displays of wealth and power. Only royalty, the aristocratic, and society’s elite were permitted inside these libraries. “Public here” meant “for the public good,” meaning they were for the upper classes to use for deciding what was “good” for the lesser classes. “Public” never meant who was allowed in.

Another disqualifying aspect was their stagnation. These libraries were little more than collection of books, and fixed collections at that. Holdings chiselled into stone or marble walls are not really conducive for updating. And for all the grief poured out over the Lost Library of Alexandria, this one probably suffered the most from this.

Appearing only two generations of Alexander the Great, the Library of Alexandria sought to collect “everything ever written in the history of the world.” It remains unknown if the library actually achieved this, but the Greeks certainly thought they had. This belief stifled creativity and hamstrung intellectual progress.

Carl Sagan pointed to this in his 1980 television series Cosmos. Mourning all the scientific texts now lost to history, Sagan’s regret is obvious. “But,” he says as the camera begins to zoom in on him, “the permanence of the stars were questioned here.” He let that hang in the air with the camera still closing in on him. “The justice of slavery was not.”

This was probably the true reason Alexandria was lost. So lost in fact that when Richard Nixon arrived in Egypt in 1974 for his tour of the Middle East, he asked if he could see where the legendary library had been. His hosts embarrassingly told him they couldn’t. No one had bothered to record its location. This sparked the rebuilding of it, which was completed in 2002.

Architecturally stunning and UNESCO sponsored, the new Bibliotheca Alexandria is, once again, a rich person’s plaything (this time the government of Egypt). Built in an Egyptian port no longer in use, amongst a population who were mostly illiterate and below the poverty line, with a government not known for upholding human rights, one wonders just exactly who this library is for?

Public Libraries as we know them did not exist until October 14th, 1852. This was when the city council of Boston, Massachusetts, ratified City Document 37, which not only created a paradigm for libraries supported by the tax dollars of those who used them, but also mandated “free admission for all, circulation of books for home use, and the acquisition of reading materials, ranging from scholarly to popular.” It was this document which quickly became the blueprint for libraries all across North America. It still remains today.

A public library is government at its best.

The Second Digression.

Mentioned above is references to Cranbrook’s “large Anglo-Saxon population.” Anglo-Saxon here being a hardly-secret euphemism for white people who spoke English. I am a fourth generation from this original group; it’s important not to romanticize them. They certainly weren’t the only ones here. “One day last week, within an hour’s time,” the Cranbrook Herald reported in 1902, “the Herald men heard people conversing in English, French, Chinese, Japanese, German, Swede, Italian and Indian [Indigenous] languages.” Then, inexplicably, the editorial concluded with “Cranbrook is surely cosmopolitan.”

Inexplicably because the newspaper usually referred to the non-Anglo-Saxons as, well, pick the vilest racial slur you can think of. Cranbrook truly had some dark days, such as the fire-chief performing in black face to raise money; the very first appearance of the Ku Klux Klan in Canada was right here in Cranbrook; the unforgiveable crimes against Futu family; and the horrors rained down on the Indigenous. As we celebrate all that Cranbrook has become, it is vitally important not to erase or rewrite history. “That’s how things were back then” doesn’t hold water. That first generation had extreme privilege because of the colour of their skin; they had a responsibility to use that privilege to build others up.

The Library would help us all get there. 9781778282263

Leave a Reply