Between Dunbar Street & Taiwan

November 19th, 2025

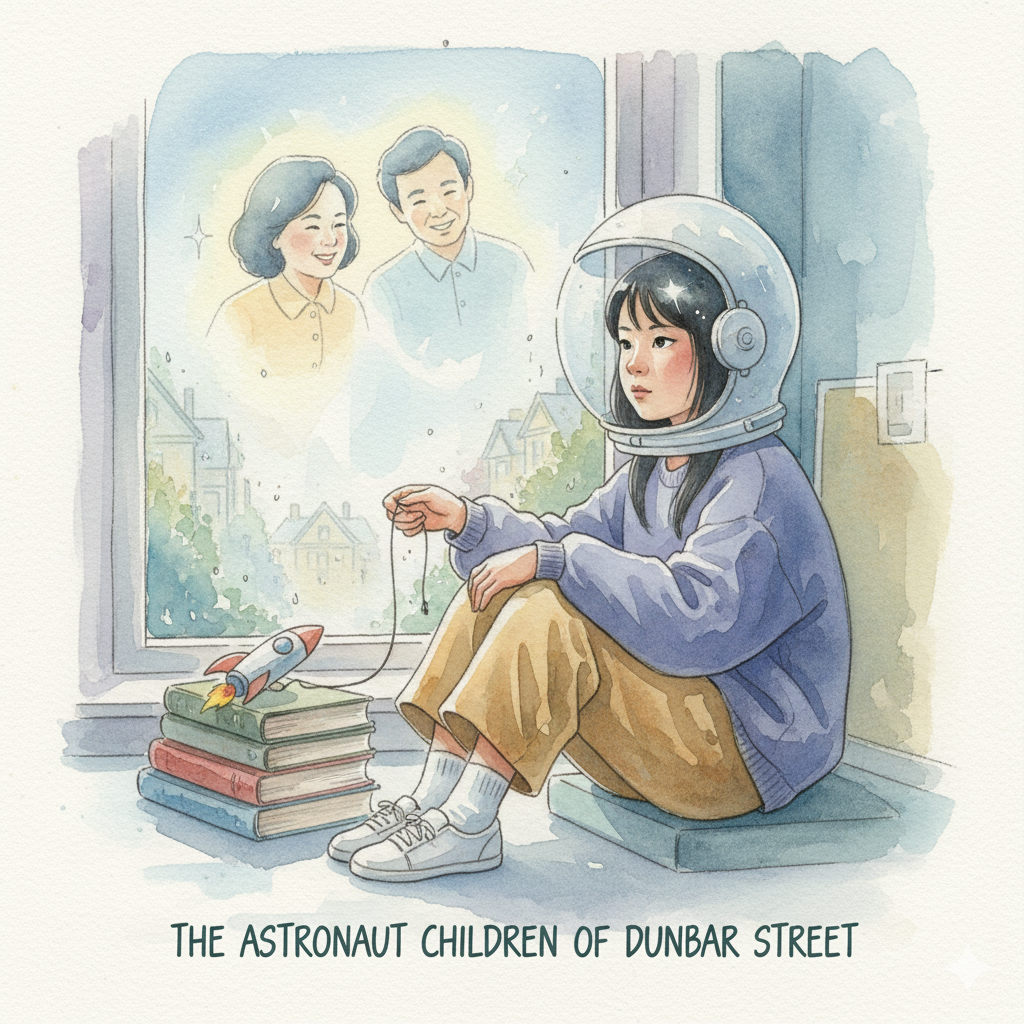

The memoir The Astronaut Children of Dunbar Street (Douglas & McIntyre $24.95) is an intimate geopolitical account of a family fractured by distance and borders, split between Taiwan and Canada. Author Wiley Wei-Chiun Ho, who identifies as Generation 1.5, explores the liminal spaces between cultures, languages and selves and is currently based in North Vancouver. The book illuminates the experience of countless “astronaut children” and “parachute kids”—children left unsupervised in Canada, the US, Australia or New Zealand after their immigrant parents returned overseas for work—a story largely absent from the literary landscape. Ho’s family emigrated from Taiwan to Canada in 1979, but a deep recession forced her parents to return to Taiwan, leaving young Wiley and her siblings behind in Vancouver with only two rules: study hard and stay out of trouble.

*

Question: What inspired you to write The Astronaut Children of Dunbar Street?

Wiley Wei-Chiun Ho: I have wanted to share my story all my life, but lacked, first, the language to describe the complicated grief of transnational separation, and then, as I got older, the courage to revisit painful scars. When people asked about my childhood, I found it extremely difficult to talk about my parents’ absence and the omnipresence of that absence. It was easier to minimize my experiences and joke about them, or let people project their harmful assumptions on me, for example, as a spoiled kid in a McMansion. It wasn’t until I became a parent myself that the traumas of my youth came flooding back. I started to get interested in astronaut families and parachute kids. I found academic papers, but very little in the way of narrative stories. That’s when I realized I needed to tell my story—to give voice to repressed silence and to provide a glimpse into the lives of unsupervised children behind closed doors.

Q: As this is your debut book, what was your process for writing The Astronaut Children of Dunbar Street?

WH: I started by writing a short story called “Camping for New Canadians” (one of the chapters in my memoir). The story got me into the 2019 Emerging Writers’ Intensive Workshop at Banff Centre, where I workshopped my piece with the incredible Kyo Maclear and a thoughtful cohort of writers. From there, I began to notice genuine interest and curiosity about astronaut families from neighbours, friends, and teachers who came in contact with us. That inspired me to expand the work into a long-form project. It’s taken many years and many tears to arrive at this book. The process of memoir writing is demanding. It requires the writer to excavate family histories and memories, to re-examine old assumptions and long-held beliefs, to get at the emotional truth of what happened. It’s what the writer Vivian Gornick describes as the real story beneath a given situation. This can be exhausting, so the work is necessarily slow and requires a ton of reflection and patience. There were many times I wanted to quit, but the project refused to let me go. Perhaps that’s the writer’s strongest indicator to keep going.

Q: Can you elaborate on the significance of your research on astronaut families?

WH: I first came across the term “astronaut family” in the work of the anthropologist Aihwa Ong in her book, Flexible Citizenships: The Cultural Logics of Transnationality, published in 1999. She used the term to describe middle-class families from Hong Kong and Taiwan who immigrated to countries such as Canada, the US, Australia, and New Zealand. Though there is scholarly writing on this subject, I rarely came across personal accounts. In particular, I saw a gap in the literature about the Taiwanese diaspora and its astronaut families, even though there are so many of us around the world. So, I applied for, and was thrilled to receive a Canada Council for the Arts grant to pursue research and writing. I tracked down other astronaut families in Canada and the US, and lined up interviews. The majority of them eventually cancelled or truncated their interviews. Most found it too painful or difficult to articulate their experiences and feelings. In the end, I came away with only a handful of interviews, none of which I could use publicly. That’s when I decided to shift the focus from a collective story to a more personal one—that of my own life—with my research forming the background.

Illustration by Brian Nguyen

Q: What was it like to write a geopolitical memoir such as yours in a fraught moment like ours?

WH: The Astronaut Children of Dunbar Street is first and foremost a family story, with my focus on the intergenerational experiences of migration and reverse migration, and the effects of long-term separation on a family from Taiwan. I never set out to write a political book. But, in the process of researching and writing, it became clear that I could not fully narrate my story without engaging in the messy intersection of political, economic, colonial, racial, and ancestral legacies. To be honest, it is terrifying to engage in this arena, but as many of my wonderful mentors have told me over the years: All writing is political, and being afraid is the best barometer that you’re creating something that matters.

Q: Can you discuss the challenges you faced in transitioning from rarely talking about your childhood to sharing deeply personal experiences?

WH: I still find it hard to talk about my childhood experiences, which is why I wrote this memoir —to give more nuanced expression to the layers of contradiction growing up: the privileges and privations, the freedoms and constrictions, the confusions and longings, the shame and even a strange kind of pride. Most astronaut kids, including my own siblings, don’t like to discuss the subject, so I have kept them largely anonymous in my book to protect their privacy.

Q: Did writing this memoir bring up difficult memories, or did it help process the grief you experienced as a child?

WH: I started keeping a diary from the age of 11, so I have many records of my days as a youth. Although I mention sadness and confusion in my diary entries after my parents left, I was young and often wrote only the surface of things—what happened, when, and with whom. The traumas are there, but hidden. Only as an adult looking back could I detect the repressed emotions. When I revisited my old diaries to write this book, I felt the acute confusion of my younger self and a deep adult need to protect her. It was difficult for me to confront all that vulnerability by myself, so I worked with a hypnotherapist and then a narrative therapist to process the more traumatic events. Gradually, I let go of self-blame and anger to finally understand my whole story. Though painful, the process was healing and fruitful.

Q: In what ways do you believe your experiences as an astronaut child shaped your identity and outlook on life?

WH: So much. I owe my insecurities, my need to please, as well as my adaptability, independence, and optimism—all the bad and the good—to having struggled hard for ways to belong, to survive, and to carve out an identity in the in-betweenness of relationships, cultures, and places.

Q: How did the act of writing this memoir help you navigate the complexities of your past and find moments of hope and tenderness amid the traumas you faced?

WH: It was a very slow process. From the first draft to the final draft took eight years. The story changed a lot over time, not so much in content as in tone. The early drafts were full of indignation, as I processed my anger and grief over historical injustices and personal losses. It took more drafts to stop blaming people, including myself, and to embrace the humanity in my story, which I’ve come to see as deeply universal because it is rooted in circumstances beyond our control. Ultimately, I discovered the necessity of embodying multiple distances—the moment in childhood, the moment of the narrator telling the story, and the moment of the present self—and of telescoping between perspectives. In so doing, I gained much greater depth and compassion for everyone in my memoir.

Q: What do you hope readers will take away from your memoir in terms of understanding the motivations and behaviours of astronaut parents and their children?

WH: My book covers a large swath of time, about fifty years. Initially, I set out to write only about my childhood, but I realized the importance of sharing the long-term impacts of separation on a family—the ‘fallout” from generation to generation to generation. In the end, I brought in personal elements from childhood, adulthood, and motherhood. If my book had a “goal,” it would be to bridge the internal, intergenerational, and intercultural divides within our families and communities.

Q: How do you envision your memoir contributing to a broader conversation about the hidden costs of transnational families and the potential for healing through sharing one’s experiences?

WH: Today, there are untold numbers of astronaut families in Canada and other countries, kids in nice houses who grow up without their parents, and parents who work hard to provide for and try to hang on to their children from half a world away. In telling my story, I hope to shed light on the complex circumstances, motivations, and impacts behind migration and reverse migration—as well as the benefits and the deep costs. I hope readers will think twice before judging appearances and that other astronaut kids will feel less silenced and alone. Denial of emotions, submerged rage, and dysfunctional silence are far too common in so many families. Shame and grief are hidden costs that exact deep damage over time. I hope my story provides a starting point for others to open up about their own experiences, because open dialogue is the portal to greater peace, connection, and much-needed community. 9781771624794

Leave a Reply