Ain’t goin’ to Vietnam

Tens of thousands of young Americans came to Canada to escape military service in Vietnam and went on to lead productive lives here as told in a new homage to them.

November 05th, 2025

Joline Martin left the US because of the Vietnam War. She is committed to advocacy and storytelling. War Resisters is her first book.

“Manny Meyer, an aspiring musician whose father had a career in the military, could not see the point of the war. ‘We were going halfway around the world to kill the Vietnamese,’ he said. ‘They were just people, and we did not even know them.’”

Review by Tom Hawthorn

They came from farms and college towns, from striving blue-collar families and comfortable bourgeois backgrounds, from Iowa and Minnesota and California.

And they seem mostly to have come in Volkswagen Bugs.

For about eight years starting in the mid-1960s, tens of thousands of young American men and women crossed the border to begin new lives in Canada. Some were draft evaders, some deserters, some simply fleeing “Dodge” because they knew trouble was brewing at home. They were war resisters, opposed to the American conflict overseas with Vietnam and certain they did not want to kill or be killed in an immoral war.

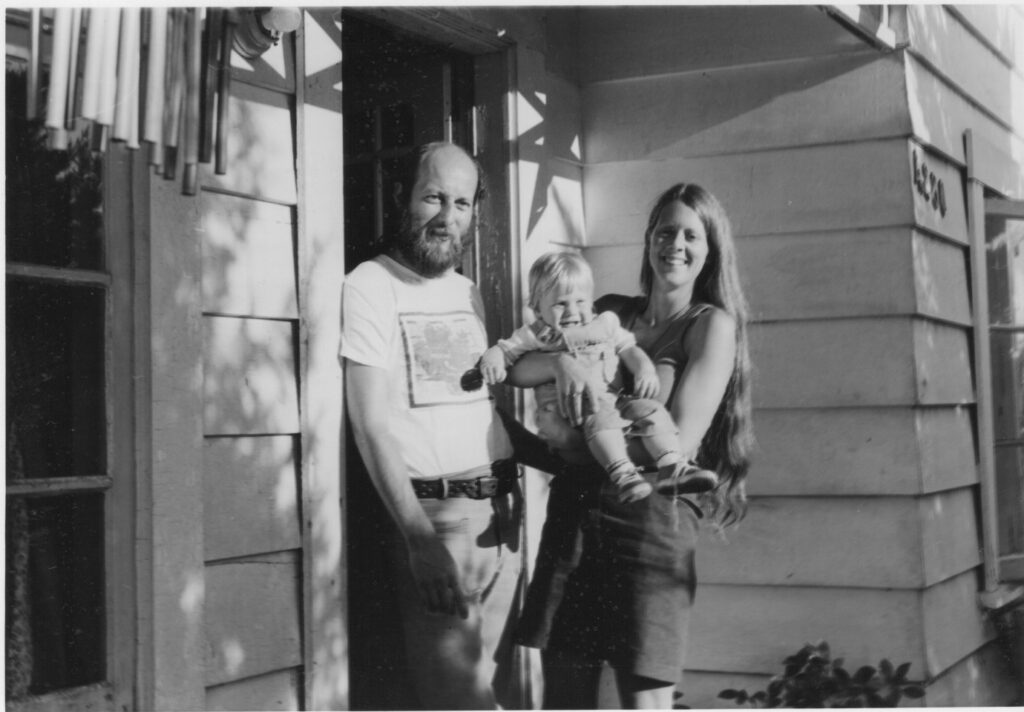

Jeff Hartbower and his partner Jo, in Vancouver, shortly after their arrival in 1967. “It was the Vietnam War ‘pure and simple’ that led to Jeff and Jo leaving the United States.”

“One thing that really affected me as a teenager of draftable age was the mainstream media’s coverage of the war,” recalled Oliver Clarke. “They had reporters in the trenches with American soldiers. We could see the effects on the soldiers first-hand. While one of the NBC reporters was waiting in a trench, a soldier who had been shooting at the enemy jumped back into the trench. The reporter asked, ‘Soldier, do you know why you are here?’ and the soldier answered, ‘I have no idea.’”

Manny Meyer, an aspiring musician whose father had a career in the military, could not see the point of the war. “We were going halfway around the world to kill the Vietnamese,” he said. “They were just people, and we did not even know them.”

Fleeing north often came after desperate bids to avoid compulsory military service. “They claimed medical issues, homosexuality, psychiatric conditions, allegiance to radical groups or intentionally flunked the aptitude tests,” Joline Martin writes in War Resisters: Standing Against the Vietnam War (Caitlin Press $26).

Tim Haley playing the mandolin with another student at a special school on a dude ranch he attended as a teenager. His wife Emma said she didn’t want Tim going to Vietnam to fight. “No way. We are going to Canada,” she said.

Having graduated in 1964, Meyer faced the draft. He claimed to have asthma, mistakenly thinking the condition made him ineligible. Instead, he was given 1-A status and cleared for military service. Before being sent to what he was certain to be a hellish assignment, Meyer and a buddy lit out for the West Coast to find paradise. He’d already had adventures in life, including becoming a pilot and learning banjo from a musician who would years later compose “Dueling Banjos,” the theme music for the 1972 movie, Deliverance. In California, Meyer’s neighbour was spiritual leader Baba Ram Dass, a former mental health professional formerly known as Richard Alpert. The novelist Ken Kesey, who wrote One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest before leading a band of “Merry Pranksters” around the US, lived down the block and Stewart Brand of the Whole Earth Catalogue, which would serve as a combination Bible and how-to manual for long-haired back-to-the-landers, including draft evaders in Canada, was in the neighbourhood.

To protest the war, Meyer flew a small plane over the Bay Area over which antiwar leaflets were dropped. Figuring he was going to be drafted, he tried to enlist in the Air Force Reserve as a way of avoiding active duty in the warzone. Instead, his asthma claim was accepted. His status went from 1-A to 4-F (meaning unfit for military service).

A friend of a friend who brought a delicious bag of apples from Denman Island convinced Meyer and his wife to head to British Columbia, where he joined a traveling hippie circus.

Meyer is one of a dozen resisters who wound up on Vancouver Island who were interviewed and profiled by Joline Martin. Many arrived here broke and desperate, relying on a loose network created by the earliest arrivals and Canadian sympathizers. The folks portrayed in the book survived, grateful for Canada as a refuge from madness, and several continue to contribute to their adopted communities.

Among the fascinating characters profiled is Marvin Boyd, a fugitive from the U.S. military, the American legal system and, most worrying of all, a bail bondsman with Mafia associations. Boyd comes to BC after being inspired to travel here by a textbook about the flora and fauna of what is now known as Haida Gwaii. He winds up getting a government job before losing it when the government realized he was not a citizen. Eventually, Boyd finds success operating a small airline.

Alternating chapters of War Resisters offer potted histories of the times, though these summaries are too perfunctory to offer much insight. An exception is a chapter on Canada’s changing immigration rules during the period, which helps explain why some of the newcomers sought to disappear into the Canadian wilderness like outlaws, off the grid and, hopefully, away from the attention of authorities.

U.S. president Jimmy Carter’s amnesty in 1977 allowed many of these war resisters to return to American hometowns and families some feared they might never see again.

From the Kootenays to the Gulf Islands, from Vancouver’s Kitsilano neighbourhood to far-flung resource towns, these 20th century war resisters followed earlier generations of arrivals in building new lives. They came seeking refuge from a turbulent world, having made a difficult decision with legal, as well as moral, consequences. 9781773861685

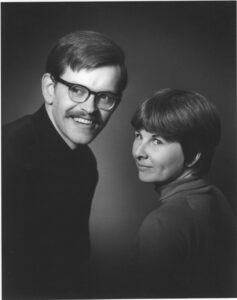

When given orders to go to Vietnam, Tim Fuchs drove to Canada instead. Above, Tim with his wife, DD in Vancouver, 1974. They retired on Denman Island. “We, at no time, ever considered moving back to the States. We truly enjoy our life in Canada,” says Tim.

Tom Hawthorn’s anecdotal history of professional baseball in Vancouver, Play Ball!, was published by Echo Storytelling earlier this year.

Good to know about this. And you should know about my novel Centre/Center (Talonbooks, 1992) which deals with this period.When I held a panel discussion with draft dodgers who live in our Sunshine Coast community, the room was packed to overflowing with those who had similar experiences or who sympathized.It is still an emotional topic. I am thankful to have joined the migration to Canada, arriving from California in 1970. Here’s what one reviewer had to say about Centre/Center:”Another novel about American baby-boomer angst over the 1960’s legacy and the repercussions of Vietnam, you say? But wait, this one is really good. In fact (Centre/Center ) is a wonderful example of a novel that both illuminates and transcends the plight of a particular group of people in a particular place at a particular time. Tolstoy would have been proud.” Language and Literature maryburns.ca