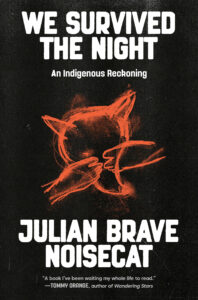

The beat of Julian Brave NoiseCat

A champion powwow dancer tells of survival and spiritual return via storytelling and the power of love and ancestors.

October 29th, 2025

Julian Brave NoiseCat is a writer, Oscar-nominated filmmaker and student of Salish art and history.

“Marketed as genre-defying, Julian NoiseCat weaves memoir, traditional stories and reportage into an unconventional whole. I found myself reading it one chapter at a time, often setting it down to absorb what I’d just read. It wasn’t a difficult read, so much as the shifts in form and tone moved me from my norm of reading cover to cover in a linear fashion. That’s the power of design: each section stands on its own, inviting—even demanding—reflection before moving on. The effect is less a single narrative journey than a series of deep encounters, cumulative rather than continuous.” –Odette Auger

Reviewed by Odette Auger

Within pages of Tsecwínucw-kuc, We Survived the Night: An Indigenous Reckoning (Random House Canada $39), the genius of the structure is clear. Just as Julian Brave NoiseCat (St’at’imc, Secwépemc) moves deftly from journalism to directing (award-winning documentary, “Sugarcane”), his book writing takes a circular, but steady path through oral history, father-son relationships, trickster tales, environmental reporting and love.

The opening scene digs deep, quickly. We’re brought to his father being abandoned in a residential school’s incinerator. It’s Julian NoiseCat’s choice of words that jarringly brings us into this moment as a watchman’s flashlight casts “rays of light onto rubbish and soot,” inside a garbage burner.

“Within was a newborn,” continues Julian NoiseCat. “The authorities called him ‘Baby X.’ And he was my father.”

“Within was a newborn,” continues Julian NoiseCat. “The authorities called him ‘Baby X.’ And he was my father.”

Babies in the incinerator is a familiar story to Indigenous people across the country. I grew up somehow knowing this happened more than once, in more than one place—despite being sheltered from even knowing my mom went to an Indian Residential School (IRS) until I was an adult.

Sliding like Sek’lep the shifting coyote, the story brings us to learning that Julian Noisecat’s father is Ed Archie NoiseCat, a renowned Secwépemc artist. Readers learn about Julian Noisecat’s talented father, whom he describes as a “combination of character, comedy and tragedy…He draws the eye and fills up a room,” and about being raised by his Harvard-educated Jewish/Irish mom who, Julian NoiseCat explains, has been his editor since day one and is “intellectually, emotionally, and socially brilliant.” Readers are taken on a journey into the Indigenous art world, community and NoiseCat family. His auntie is Martina Pierre (Lil’wat) who wrote the Women’s Warrior Song, gifted from a spider during a ceremony, to honour missing and murdered Indigenous women.

Julian NoiseCat brings fresh Coyote storytelling and shares lineages while simultaneously myth-busting (about topics such as Indigenous casino wealth, free education and that Indigenous people don’t pay taxes).

Marketed as genre-defying, Julian NoiseCat weaves memoir, traditional stories and reportage into an unconventional whole. I found myself reading it one chapter at a time, often setting it down to absorb what I’d just read. It wasn’t a difficult read, so much as the shifts in form and tone moved me from my norm of reading cover to cover in a linear fashion. That’s the power of design: each section stands on its own, inviting—even demanding—reflection before moving on. The effect is less a single narrative journey than a series of deep encounters, cumulative rather than continuous.

At times, Julian Noisecat’s hybrid form creates shifts in voice. There are moments where NoiseCat is writing from a mixed lens, for example, referring to “ancestral tongues… fast slipping from the Land of the Living to that of the dead … Salish languages are what linguists call agglutinative,” then circling back to the teaching when we “tell these stories…the Coyote truths they hold come back. Because death is not permanent—at least not this kind of death. No, this cultural and linguistic death is, as the trickster told us, like sleep.” Our ancestors speak the languages, “and they could bring it all back, if only we could reach them.”

In the “Exodus” chapter, there’s a biblical comparison of the Israelites’ forty years of wandering to the Ouje-Bougoumou Cree’s seventy years of waiting for land claim settlements. Yet I find linking the biblical Moses leading his people out of Egypt to Chief Abel Bosum leading his people to a new home after they had been cast out of their own land is oddly out of step. The bible story is an example of people lacking faith and engaging in rebellious disobedience, leading to a generation-long punishment from their God. The Ouje-Bougoumou Cree story is one of injustice against people who have been displaced by industrial activity.

In the same chapter, a later line that imagines the author’s great-grandmother as “a lot like” one of the Cree women profiled momentarily, blurs the boundary between witness and participant. These brief sudden jogs show both the reach and the risk of Julian Noisecat’s genre-defying approach. It’s a structure that invites empathy and connection, even as it sometimes unsettles the narrative.

The first chapter is titled “In the Beginning” (the first three words of the Bible) although Julian NoiseCat lets readers know “I don’t go to church.” These touches have the effect of underscoring Julian NoiseCat’s calling out of Churches working with the State to advance the imperialist, capitalist goals of extraction and which impact land, waters and people—dismantling communities, families, lives.

NoiseCat holds space for love, grief and renewal in equal measure. “At the end of each Coyote Story, the Coyote People have always understood that Coyote may die, disappear, or turn to stone, but he was never truly gone,” writes NoiseCat. “He is our ancestor. He will always be part of us. We will always be part of him. And in the end—some say any day now—he will come back.”

Rhythm unites the structure and Julian NoiseCat’s faceted style is executed with a steady pace and strong vision. As he is a champion powwow dancer, the comparison comes to mind of different dances having specific and unique footsteps, but which all move in time to the drum’s rhythm.

That beat is the spine supporting the varied chapters of Julian NoiseCat’s We Survived the Night. 9781039001336

Julian NoiseCat at a powwow.

Odette Auger, award-winning journalist and storyteller, is Sagamok Anishnawbek through her mother and lives as a guest in toq qaymɩxʷ (Klahoose), ɬəʔamɛn qaymɩxʷ (Tla’amin) and

ʔop qaymɩxʷ (Homalco) territories.

Leave a Reply