The cool kids

Katharine Rollwagen shows how Canadian stores and marketers worked with youth from the 1930s to the 1950s to create the teen market.

October 22nd, 2025

Katharine Rollwagen is the Acting Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Humanities, VIU.

“By 1957, a Maclean’s magazine article on ‘The Scramble for the Teen-Age Dollar’ explained that retailers and advertisers were ‘out-hustling each other to cash in on the market that just grew up.’”

Review by Gene Homel

If you are a baby boomer old enough to remember the fashions and fads of the sixties, you might assume that the Canadian market began to cater to teenagers only then.

Not so. The sixties teen market had its origins in the 1930s, 40s and 50s, according to Katharine Rollwagen, author of The Scramble for the Teenage Dollar: Creating the Youth Market in Mid-Century Canada (UBC Press $110 h.c.)

In her interesting book, Rollwagen shows the remarkable ability in the middle of the last century of Canadian retailers, advertisers and the mass media to laser-focus on teens as a specific, special segment of the market. After all, eight million babies were born in Canada from 1943 to 1964, and a million immigrant children arrived over the same period. Concentrating on this teen market secured young people as a vital part of expanding consumer capitalism. By 1957, a Maclean’s magazine article on “The Scramble for the Teen-Age Dollar” explained that retailers and advertisers were “out-hustling each other to cash in on the market that just grew up.”

As a veteran of the fifties’ hula hoops and Davy Crocket coonskin caps, Rollwagen is on target when she explains that “Canadian retailers and advertisers worked to construct an image of the teenager that would appeal to young people and encourage them to associate consumer goods with their stage of life.”

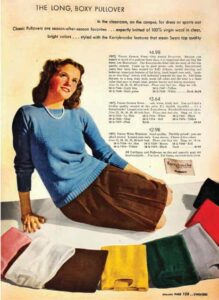

Sloppy Joe boxy and long sweaters for teens, 1946.

In this way, Canada’s consumer-oriented society tied us to the market and fixed our identity as commodities and citizens. To this, Rollwagen later warned of the ample evidence “that growing up in consumer society can be detrimental.” For example, keeping up materially with one’s peers can be negative psychologically, especially for teens from lower-income families. Gender expectations can also be problematic, as can discouraging independence from group think. Other detriments include environmental waste and poor working conditions overseas in lower-paid countries.

The author used archives of the T. Eaton Company, the dominant department store of mid-century, which had 48 stores in the 1960s and was the fourth-largest employer in Canada. Eaton’s proclaimed itself “The Store for Young Canada.” Rollwagen describes how the store solicited the attention and input of popular, “cool” high-school students by approaching the schools themselves. Eaton’s set up what it called the Junior Council for teen girls and the Junior Executive for teen boys to understand teens’ consumer desires and styles, and help with fashion shows.

The “Hi-Spot” in a 1940s store was an area “where you and all the ‘coke crowd’ can gather to gossip about clothes and listen to music.” Teens were groomed to become avid Eaton’s customers as well as paid, or volunteer employees—on a gendered basis, of course.

This two-way exchange is an important element to understand consumption under capitalism. Fashions were not just a product of dictation by business; instead, business had its ear cocked to what consumers at the grassroots desired; it was a complex, two-way street.

Some fashions from the grassroots provoked anxiety on the part of marketers and authorities—for example, Sloppy Joe sweaters popular with teen girls and Zoot Suits popular with male youths. The Sloppy Joe was an oversize knit sweater; the Zoot Suit was a distinctively tailored suit associated with the lower classes or delinquents. Some manufacturers capitalized by producing Zoot Suits and marketing clothing with the Sloppy Joe label. These fads from the Forties tied into marketers’ dual notions that teens were both reasonable and rational consumers, and immature and irrational fad chasers.

Not surprisingly, marketers emphasized sex appeal to teen girls: “Just listen to ‘em whistle when you go by wearing this [outfit],” proclaimed one ad.

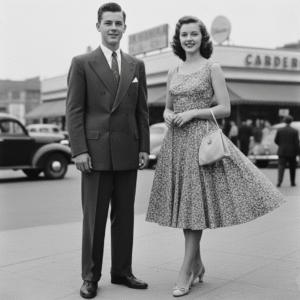

Marketers presented teens as ideally slender and their slim-fitting dresses were “plentifully supplied with the lively detail that rates second glances.” Teen males, on the other hand, were to wear suits that denoted preparation for responsibility and business.

Magazines also cemented the marriage of teens with the market, especially “co-eds” (high school and college girls). Co-eds could navigate adolescence, including menstruation and acne, with the

support of products and images provided by Chatelaine, Canadian Home Journal and Mayfair. With the “right” commodities, a co-ed in and out of the classroom could present herself as attractive and popular. “Go Back a Smarter Girl” referred to fashion, not book learning. Other slogans were more overt in what we consider sexism today: “Don’t get the idea that because you got a first in History you don’t need any lipstick.”

Rollwagen sometimes employs current faddish language in her analyses. The image of the co-ed, she writes, presents “the so-called typical teenager as a white, middle-class, cisgendered, heterosexual student, an image that excluded many Canadian youth.” Apart from class hierarchy, I don’t believe that many youths would be excluded by this description in the 1930s to 1950s in Canada. Of course, working-class young people were just as concerned with fashion and fads, and also had money to spend. Rollwagen also refers to urban Canada—Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver and so on— as “settler” societies, as in “white settler femininity.”

Quibbles aside, Rollwagen’s book will appeal to readers interested in fashions, marketing and youth culture, whether or not they played with hula hoops. 9780774869881

Gene Homel has been a faculty member at universities, colleges and institutes since 1974 teaching Canadian history and politics.

Leave a Reply