No map, just instinct

From near-death escapes to humanitarian missions, John Huizinga shares how instinct, courage and curiosity shaped his unconventional life.

October 15th, 2025

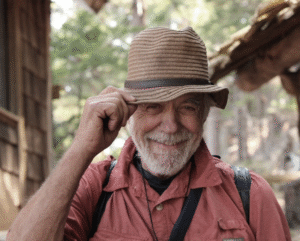

John Huizinga is a storyteller, a logistician, a mechanic and a humanitarian.

“When I am in an unusual or uncertain situation, I am supremely present. All other thoughts drop away—only the present exists.”

John Huizinga’s A Somewhat Incautious Life: The Many Near Deaths of John Huizinga (self-published $34.99) is an unconventional memoir chronicling a life lived on the edge—from surviving occupied Holland during WWII to clearing land for the Bennett Dam, tree planting, smuggling across the Mexican border and working with Doctors Without Borders in global conflict zones. Each near-death experience connects a lifetime of risk, discovery and humanity. A lifelong adventurer and storyteller, Huizinga now resides in the interior of British Columbia, surrounded by books and memories of a life fully—and incautiously—lived.

*

BC BookLook: Your memoir states, “I’ve almost died a lot of times. I’ve had a great deal of plain old good luck in my life.” Given the many near-death experiences that form the core of your book, A Somewhat Incautious Life, how do you differentiate between incautious living and simple good fortune? What is the most profound survival lesson you hope readers take away from your adventures?

John Huizinga: Experiencing great good fortune, time and again, encourages me to live less cautiously, to take chances. When I am in an unusual or uncertain situation, I am supremely present. All other thoughts drop away, only the present exists. The first thing is to orient—where am I, what the physical landscape is like. Secondly, observe what is going on. Is there a threat? What does it look like? And then decide what to do to counter the threat, what makes sense to stay on top of the situation. Or to just survive! Next, act! Take action! Do not wait for more information, act now! Re-orient right away! The situation had changed. Follow the loop, observe, decide and act. I believe that all of this comes naturally, following our instincts. The critical part is not to think through it too much—decide and act!

BCBL: Your life spans from occupied Holland during WWII to immigrant life and the early development of northern British Columbia. Can you describe the personal impact of moving from the intense environment of post-war Europe to the massive, wild landscapes of Canada?

JH: For me, I was eight years old when we immigrated. Coming to Canada was a huge adventure, we were four brothers, all in the same age range (six to twelve), explored endlessly and reveled in the wide open spaces. For our parents, immigration was an earthquake. It was a major upheaval of their lives. Nothing was familiar, not even the language. This new life was very difficult for them. In the end, my parents also lost their children. We, as children, soon learned a new language and learned a new way to see the world. By the time we were teenagers, our parents no longer understood us. We had become “them.”

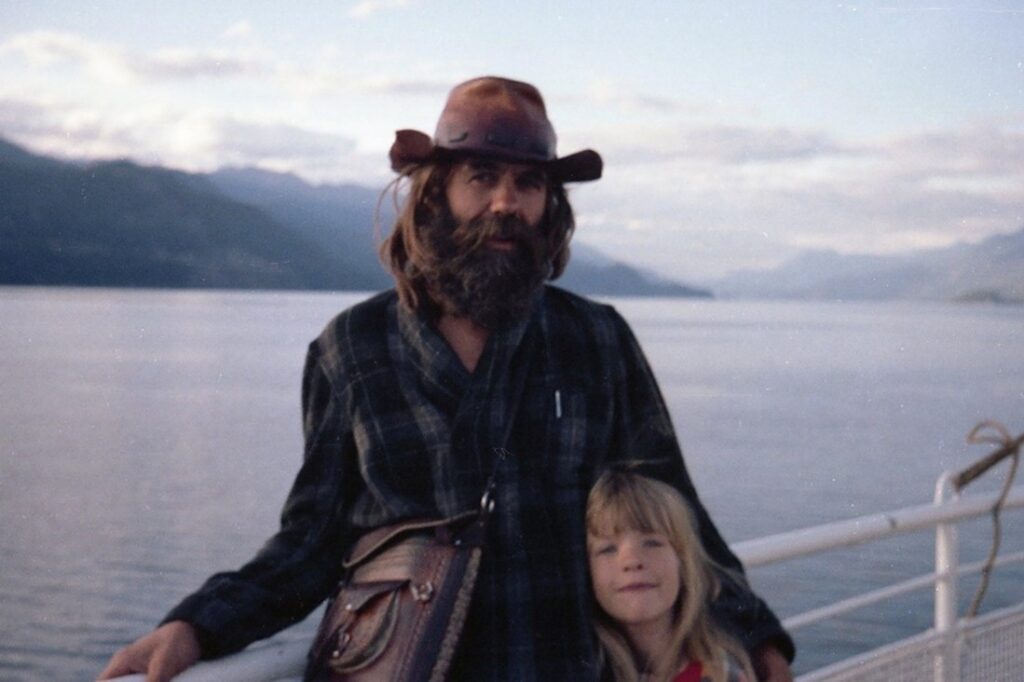

John and his daughter, Sjoukje, on the Kootenay Lake Ferry, 1979.

BCBL: You’ve lived in the Kootenays for over four decades, homesteading and building your own house on Elkin Creek. What initially drew you to the Kootenay Valley, and how did your various global experiences—from refugee camps to smuggling operations—shape the kind of deliberate, self-sufficient life you chose to build there?

JH: My friend from university days, Dirk Brinkman, had moved to BC and had been building a house on Kootenay Lake close to Riondell. We, my wife, Sara and I, drove to BC to witness the wonders he described in his letters. We fell in love with this beautiful place. A pristine Kootenay Lake ringed by towering, snow-capped mountains and the self-sufficient lifestyle, where Dirk was building his own house and planting trees to satisfy the demands of Mammon. That same summer, we bought an old apple orchard along with an old, falling-down farm house across the lake in Queens Bay. The skills I learned in becoming a mechanic, homesteading, building our house as well as working as a faller in northern BC, were essential to successfully do the work required of a logistician for MSF (Doctors without Borders). I believe that growing up on a farm, where we had to self-manage, was the foundation for a self-sufficient life. We never thought to call in so-called “experts” for anything—whether it was building something, fixing machinery, butchering a pig or delivering a difficult calf. We just figured it out and made it work!

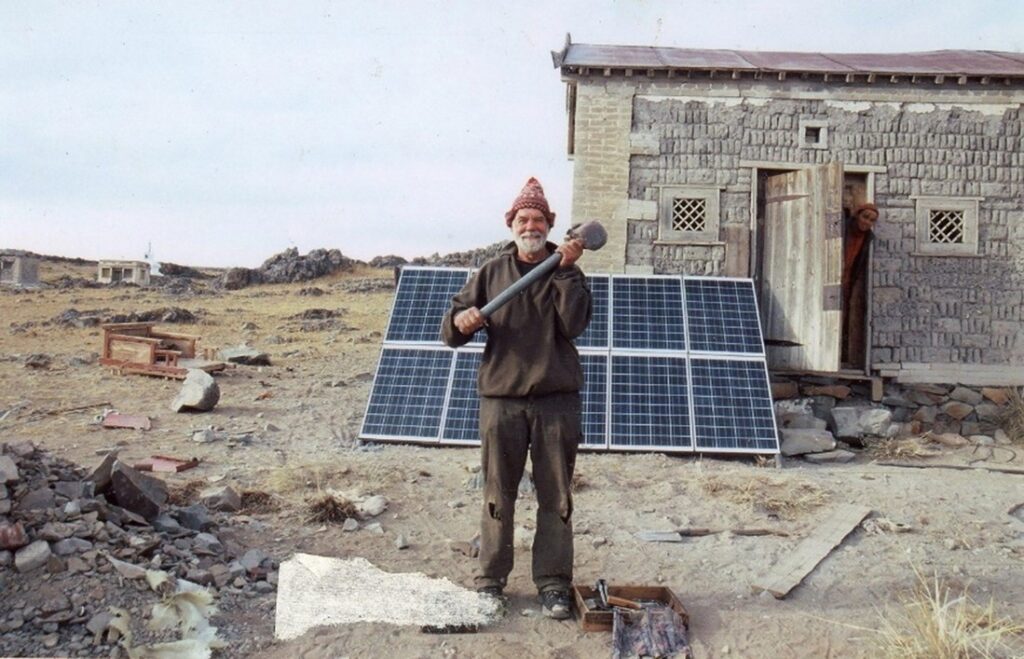

John Huizinga installed this solar system in the Gobi desert.

BCBL: Your career path is extraordinarily diverse, moving from the physical work in Northern BC to humanitarian work with MSF in Ethiopia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. What inspired this significant pivot to international aid work, and how did your previous skills translate to the world of refugee camps and logistics?

JH: My father possessed a wanderlust. I liked those footsteps. Had I been born in another time, I would have been an explorer or a revolutionary. The opportunity offered by MSF looked like one hell of an adventure. The humanitarian aspect was very satisfying but it was the icing on the cake.

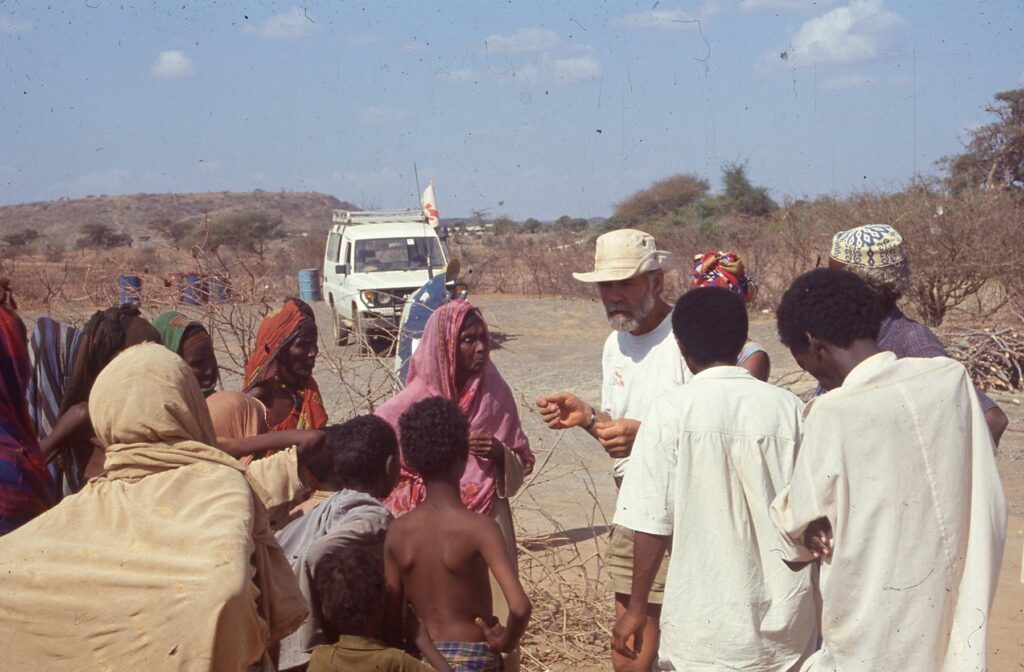

BCBL: You are currently writing a book specifically about your time with Doctors Without Borders. What will this new book focus on that the memoir might only touch upon, and what made you decide to dedicate an entire volume to your MSF experiences?

JH: The new book I am writing, expands on the stories in the memoir. As well, it is a more complete and thorough description of being a logistician on a MSF project, how a MSF project works on the ground and how different these projects can be. It’s like they were happening on different worlds. I decided to write a book on the MSF experiences because there are so many good stories that come from spending a year living with the project and then repeating this somewhere else, somewhere contrasting. Also, I believe that it’s important for people to learn what MSF has been doing for the world and how it works on the ground. MSF is an essential presence in our difficult and unjust world.

Huizinga worked at the MSF feeding centre in Somali.

BCBL: The excerpt from your book mentions trying your hand as a spy in Vietnam and Cambodia. Can you share a brief, compelling anecdote from this period that illustrates the kind of “incautious life” you were living at the time?

JH: I made a mistake answering a simple question from my minder. When I returned to the out-of-the-way place I was staying, the owner—an Australian man, himself in Cambodia, because there were no extradition treaties—rushed at me saying, “You gotta’ leave. The police were here looking for you. The really bad ones, you are dangerous. I went to my translator’s house. You must leave Cambodia immediately, all roads leaving Phnom Penh have checkpoints. But I can get you on a train that is forbidden to foreigners.”

The train took me to Sihanoukville on the coast. On my translator’s advice, I stayed in a whorehouse— safer for me than a hotel. The madame, who spoke English, arranged for a motorcycle driver, who drove me to the Thailand border, about one hundred kilometres away. He showed me how to avoid the customs booths for Cambodia and Thailand by taking a path through the forest. The essential aspect of my escape from Cambodia was that I was dependent on other people—strangers, no less. Any one of them could have turned me in. This confirmed my belief that most people are empathetic and want to do what’s right. It’s so important to know that there is no need to hesitate in throwing yourself on the mercy of strangers, to know that almost all the time, this will work out. I have other examples.

BCBL: Given the scope of your adventures—from a spy in Vietnam to a logger in BC to a logistics expert for MSF—what advice would you give to someone who feels stuck in a conventional path, or to a fellow writer trying to capture a life as sprawling and unconventional as yours?

JH: For those who feel stuck in their path, I’d say: “Close your eyes, take a deep breath and jump off your comfortable porch. Just go for it!” For a new writer, start small, pick a theme, begin to write, one story at a time. Find someone who will hold you accountable. I would like to advise you to call my daughter. Without her steadfast encouragement, my book would still be an idea or a partially finished project. The key is not to give up, to keep going. Writing a book is not an instant gratification sport. 9798329221800

Leave a Reply