Kelowna’s past and future

September 25th, 2025

Historian and former Kelowna city councillor Sharron J. Simpson has dedicated much of her career to preserving community and family stories. A fifth-generation Okanagan resident, she has published numerous local histories, including Kelowna General Hospital: The First 100 Years, 1908–2008 (Manhattan Beach, 2008) and Boards, Boxes and Bins: Stanley M. Simpson and the Okanagan Lumber Industry (Manhattan Beach, 2003).

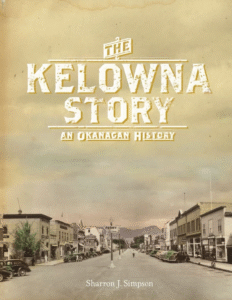

Her latest work, The Kelowna Story: An Okanagan History, Second Edition (Harbour Publishing $38.95), expands on her acclaimed illustrated history with new material up to 2025. Covering the full sweep of the region’s past—from Indigenous presence and the arrival of early settlers to the rise of orchardists, ranchers, and political figures like the Bennett family—Simpson recounts the extraordinary lives of “ordinary” people who shaped Kelowna.

*

Question: What prompted you to update The Kelowna Story? The first edition published in 2011.

Sharron J. Simpson: Kelowna has grown significantly since the book was first published, and the city has become much more visible on the world stage, sometimes because of our stunning landscape, our world-class wineries or, sadly, our tragic wildfires. The first print run of The Kelowna Story sold out, so when asked if I’d like to update it and create a second edition, I jumped at the opportunity.

Q: The history of settlers in the Okanagan began in the nineteenth century—not that long ago in human history. How has the city evolved? Has it always had that entrepreneurial edge?

SJS: It’s not a long time in human history, but the “crude and unpromising little place” in 1894 has transformed itself into a world-class destination. Those early settlers came with optimism, a sense of adventure, and a willingness to work hard and to make things work. They did and still do.

Q: Can you give us some of the history of the relations between the Interior Salish people and the European settlers?

Q: Can you give us some of the history of the relations between the Interior Salish people and the European settlers?

SJS: Father Pandosy and his party survived their first winter in the Okanagan because the Indigenous community showed them how to harvest what was at hand. They then worked with the priest and other settlers as they built their homes and established their businesses. When federal government policies created reserves in the late 1800s, there were many issues, all of which impacted—and continue to impact—our relationships.

Q: Cars arrived in Kelowna in the early twentieth century; before that, ground transportation was by stagecoach. How long would it take to travel from Kelowna to Vernon by stagecoach?

SJS: I’m not sure why you’d choose to travel by stagecoach or buckboard when regularly scheduled, beautifully appointed sternwheelers carried passengers and freight from the Shuswap and Okanagan Railway connection at Okanagan Landing, near Vernon, to Penticton, and would drop you and your worldly goods off anywhere along the way. The lake was the valley’s main highway for many of its early years.

Q: Part of Kelowna’s history is the racism directed at Japanese residents, immigrants from India and the Indigenous population. Can we talk about the impact of racism in the community?

SJS: The Okanagan thrived because its early British settlers built, financed, and populated the valley and brought their culture and traditions with them. Kelowna’s history of racism mirrors that of other settler communities, and while we may condemn it today, it’s essential we’re aware of its historical context.

Q: Kelowna has gone through many changes over the years. I guess the big one is, like everywhere, the cost of real estate. Is that the biggest change you see in this century?

SJS: Kelowna has always been about a succession of real estate “booms.” People came to this area to settle, buy land and prosper. Entrepreneurs come to subdivide, build and sell. They carved up large cattle ranches into small orchard acreages, built essential, elaborate and costly irrigation schemes to ensure the orchards survived, and then sold them. They created land development companies and syndicates in various countries to fund valley development. They’ve done this through Kelowna’s entire history and continue to do so.

Q: Climate change has certainly affected Kelowna in the past few years. The fires, the heat dome and unseasonably below-freezing temperatures had a huge impact on the wine industry. What do you think the future holds for the wine industry that became entrenched in the 1960s?

SJS: Calona Wines began making sacramental wines in the 1930s, and most of the wines produced in those early years were marginal at best, but the NAFTA agreement in 1980s resulted in most early vineyards being torn out and replanted with more suitable and popular varieties. This is the foundation of our current world-class, competitive industry. Now, along with the rest of the world’s wineries, Okanagan wineries are creatively adapting to the uncertainty of climate change.

Q: Can you talk about the influence of the province next door to the city of Kelowna? Lots of Albertans have chosen Kelowna as their home, or sometimes their second home! The Bennett family and their affiliation with Alberta’s Social Credit party certainly had a huge impact on the whole province.

SJS: Albertans enjoy many parts of BC, including the Okanagan, as both residents and visitors, likely because we’re neighbours, we’re accessible, and our climate is enticing. They add much to our communities. The Social Credit party is history and had little impact on WAC Bennett, who was a populist, a social conservative, and an economic liberal. Social Credit was a party of convenience, and he did not adhere to its “funny money” policies, among others. WAC transformed BC during his twenty years in office. Bill Bennett wouldn’t likely have called himself a populist, but he also changed BC and, more specifically, the Okanagan during his time in office. Social Credit was a recognized party when he succeeded his father, and there was no need to change its name, though he did substantially change the party.

Q: The city always had a “resort” type of feeling to outsiders. Does it feel that way when you live there?

SJS: It does, but I think that’s a more recent phenomenon. Until the train arrived in 1925, Kelowna was hard to get to, and even when the Hope-Princeton Highway opened in 1949, Penticton’s beaches were the first the visitors saw. But the opening of the Coquihalla Connector in 1991 transformed Kelowna into the resort community it’s become for all of us.

Q: One last question: Do you believe in the Ogopogo?

SJS: Of course! Doesn’t everyone? The monster’s name is really a settler’s dance-hall-ditty interpretation of the Syilx nxˇaxˇaitkw: a being who reminds the Indigenous people of the sacredness of the lake. We’d all be wise to keep this in mind. 9781998526208

Leave a Reply