Colonial wear and tear

July 28th, 2025

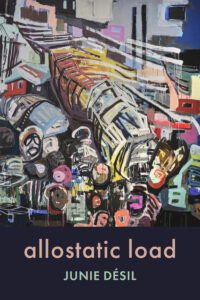

Following on from her breakout poetry collection about zombies, eat salt | gaze at the ocean (Talonbooks, 2020), which was shortlisted for the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize (BC and Yukon Poetry Prizes), Junie Désil’s allostatic load (Talonbooks $18.95) delves into the ongoing wear and tear of global racial tensions and systemic injustice. These new poems advocate for healing despite an inhospitable world.

A UBC graduate, Désil has worked in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and is currently employed at a financial organization as manager of diversity, equity, inclusion and reconciliation. She is also a mentor for The Writer’s Studio at SFU. Beverly Cramp conducted the following interview with Désil.

*

BCBookLook: How do your ideas emerge and how are they developed into poems?

Junie Désil: My process often begins with pressure—emotional, political, etc. An idea or “argument” I’m working through. Sometimes a phrase arrives, or an image won’t leave me alone. I carry it around, and see where it wants to go. I write in fragments. I rarely sit down to write a full poem in one go—though that can happen; instead, I gather lines over weeks, months—they might sit in my Notes app, or in a notebook, and when I feel like I have the space and time to sit and write, I’ll go through and start gathering those fragments. For both eat salt | gaze at the ocean and allostatic load, I had a theme and a poem and they were the foundation pieces for the larger collections and, for both of these collections, the title/foundation pieces first appeared in The Capilano Review, while I worked out what the shape of the collection would look like.

BCBL: Did you discover the term allostatic load first, or did you find the term after you had written your new poems?

BCBL: Did you discover the term allostatic load first, or did you find the term after you had written your new poems?

JD: I encountered the term allostatic load after the poems had already begun to take shape. At the time, I was reading Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake (Duke Univ. Press, 2016) and co-editing The Capilano Review’s “Weathering” issue with Phanuel Antwi. I was already engaging with Sharpe’s concept of “weather” and “total climate,” which she describes as the ongoing, atmospheric conditions shaped by Anti-Blackness. I was especially struck by her notion of “weathering” as both literal and metaphorical wear and tear.

When I came across allostatic load, it felt both revelatory and deeply familiar—like a naming of something I had long sensed. It offered a scientific and sociological frame for what I had been experiencing and observing for years: the cumulative toll of constant adaptation. These concepts—weather, weathering, and allostatic load—felt interconnected. Together, they gave me a language and an entry point to write about the compounding stress of living under systems that devalue Black life. They helped me articulate the chronic wear and tear, the slow violence and the pernicious toll these systems take on the body.

BCBL: Are these poems meant to be understood as coming from you personally, or is the narrator a literary composite?

JD: The narrator is deeply personal and also a composite. I originally intended the voice to be more diaristic, rooted entirely in my own experiences. And yet, as people read the collection, I noticed how often they recognized themselves in it. While I began in my own voice, I also considered making the narrator more of a composite—but I resisted creating too much distance, so there’s a balance of mostly me and incorporating others’ general/similar experiences. That said, it is important for readers to know this is me speaking, these are all true experiences. I could not have made them up. The narrator carries my voice, my questions, my memories; I wanted her to be specific and also porous.

BCBL: Does writing about racial micro-aggressions help you deal with them? Or is it a way of educating the broader world? Or both?

JD: Both, and more. Writing is a way for me to metabolize what might otherwise fester inside. It helps me name harm, resist erasure and sometimes even reclaim agency. My primary goal is not necessarily to educate—though if readers learn something, that’s incidental. When that happens, I try to offer enough context, but it’s ultimately up to the reader to explore further if they choose. I write to remind myself that I’m not alone. I write to connect with others who share similar experiences and to make visible what is so often dismissed or minimized. I write for those who genuinely want to expand their understanding of what it means to live in this world—for those who are willing to witness and hold the multiplicity and complexity of human experience beyond their own.

BCBL: What is your experience with “carewashing” and the impact of colonialism on healthcare? Doctors and other medical professionals don’t come off very well in these poems.

JD: I coined the term “carewashing” to describe how systems claim to care, through messaging, language or surface-level gestures, while continuing to cause harm. In healthcare, this is especially dangerous. I also try to highlight how systems of care are often underfunded, offloaded and structured to provide little more than bandage solutions. This is not about blaming individual healthcare practitioners. There are kind and committed people working within even the most harmful systems—but that’s not the point. The point is that these systems are extractive, colonial and often cause harm by design. Those working within them can become complicit—sometimes unwillingly, sometimes unknowingly and sometimes without concern. I want us to take off the rose-tinted glasses and recognize the need for truly caring solutions: ones that are holistic, community-rooted and not designed to serve profit over people. My own experiences include being dismissed, misdiagnosed and disbelieved. But these poems aren’t an indictment of individual doctors. They’re a critique of a system built on colonialism, ableism and racial bias, among other forces. I’m interested in what it means to survive and sometimes heal, within a system that wasn’t built for us. And perhaps, how we begin to dismantle those systems and imagine something better.

BCBL: The protagonist gets some relief by communing with birds and the natural world. Do you find time to replenish in nature? What else works for you?

JD: Yes. I’ve had the opportunity to live in a remote, off-grid community where nature has become a refuge. I’m surrounded by trees, I watch eagles, ravens, vultures and hummingbirds overhead and up close. I see feral sheep and their lambs grazing, go barefoot, swim in the ocean and sit in silence—immersed in a living, vibrant landscape. These moments help me return to myself. I bake. I preserve food. I nap in the sun. Read, write. There’s something radical about moving slowly, paying attention to the natural world and disconnecting from constant noise and urgency. For me, it’s not just about healing—it’s about remembering pleasure and care in ways that exist outside of capitalism, as much as possible.

BCBL: Compare the healing that comes from community to the quick fixes offered by pop culture and influencers.

JD: I understand why it can feel like the right thing—wellness gurus (and even myself, as someone trained in holistic nutrition) can sometimes be a bit evangelical about what works or what’s healing. But I also understand why it often does not feel like the solution. The mainstream wellness industry tends to offer tools and products that are unrooted—commodified, individualistic and often inaccessible. Many of these so-called solutions are also appropriated, taken out of cultural context and repackaged in ways that are expensive, extractive and exclusionary. Sure, some of it might help—until you run out of money, time or capacity. But we cannot fix deep-rooted, systemic harm with surface-level wellness practices. What works for me is relational. It’s my neighbour dropping off salmon. A friend sending a voice note to check in. In a system that often extracts more than it gives, healing—for me—happens in small acts of reciprocity. It does not come in a bottle or a hashtag. It lives in connection, presence and being witnessed. 9781772016062

Leave a Reply