#69 Pete Loudon

January 21st, 2016

LOCATION: Anyox, Observation Inlet. 55 24′ 00″ 129 47′ 00 SE of Granby Point.

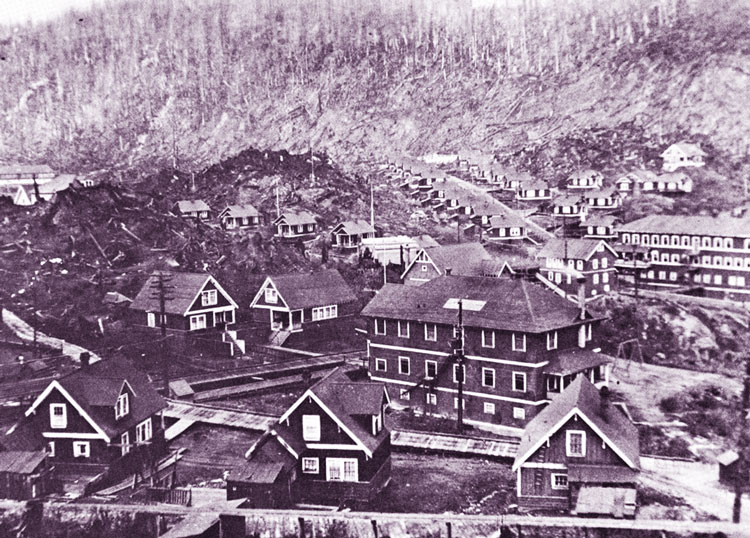

Of the numerous ghost towns in British Columbia, the most remote and bizarre is the former townsite of Anyox (pronounced “Annie Yox”) within spitting distance of Alaska, northeast of Prince Rupert, approachable only by boat. Here the Granby Consolidated Mining, Smelting and Power Company operated reputedly the largest copper smelting plant in the British Empire for twenty years, giving rise to a thriving community of 2,700 people at its peak. The mine was closed in the early 1930s, at which time nearly everyone left. A major fire in 1942 left the polluted site abandoned to bears and the elements. The veteran Vancouver sportwriter Denny Boyd was one of 480 people born in Anyox. Born in North Vancouver, another veteran B.C. journalist, Robert Peter Loudon, also lived in Anyox for ten of his first twelve years. Loudon wrote a book about Anyox, with a foreword by Boyd.

ENTRY:

Accompanied by his son, Gerry Loudon, and his nephew, Cliff McDonald, Pete Loudon returned to Anyox in 1971 on a Cessna 180 floatplane piloted by Prince Rupert logging operator Neil MacDonald who had also grown up in Anyox where his father had been the village shoemaker. For several days, Loudon and his two companions poked around the ruins of a community, resulting in The Town That Got Lost: A Story of Anyox (Gray’s Publishing, 1973), a follow-up to local historian Ozzie Hutchings’ Anyox (Hidden Creek) Mining District: The Largest Ghost Town in B.C. (1966).

The word Anyox is derived from a Tsimshian name for the main creek and Granby Bay area meaning “place of hiding,” because the Tsimshian were known to take refuge up Observation Inlet in order to avoid confrontations with the Haida. Observation Inlet, an extension of Portland Indlet, was named by George Vancouver during his survey work in 1793 when his his ships HMS Discovery and Chatham remained at Salmon Cove for almost a month of good weather in the summer.

After the company was town was founded, there were two visits per week by coastal passenger ships. CN Steamships sent their ships Prince Rupert or Prince George; Union Steamships sent either the Catala or Cardena. The town was divided between labourers and managerial staff; between the flats and the “town.” Whereas the miners and their families lived at the head of the valley, the office workers and business people lived two miles away on the waterfront. Socially, the community was also split between the “Geordies” (mainly Scots, Welshmen and miners from northern England) and the “foreigners” (Europeans).

An 18-bed hospital was built in 1913. A telephone system was installed a year later. There was a designated area outside of town for whorehouse facilities, connected with a Chinese grocery, as well as Anglican, United and Catholic churches, a movie theatre, a pool hall, the 45-room Pioneer Hotel and café, the company gymnasium and dance hall, the assay office and a separate bunkhouse for Chinese workers. A major fire demolished much of the town in 1923, but the citizenry and company were undaunted. The death blow came ten years later.

A brief but major strike was called in 1933 after union organizer Tom Bradley arrived to galvanize disgruntled miners for a newly-formed chapter of the Mine Workers of Canada, affiliated with Workers Unity League of Canada and the Red International Brigade. It was costing the miners more than half of their earnings just to eat. They went on strike on February 1 to demand a 20 percent reduction in their boarding costs, as well as bunkhouse and room rents; and a pay raise of 50 cents per day. The management cleverly asked for a brief cooling off period during which they were able to hastily arrange for a massive influx of police and hastily-hired strongmen to augment the town’s lone police constable. By February 6, the company was saying they had received orders to permanently close the entire facility. The heavily armed militia, sent by the provincial government, further intimidated the workers, 350 of whom gathered at the gymnasium for a conference. Only seven voted to continue the strike. About 320 mostly single men left town on the Prince Rupert and Prince George. The company offered some minimal improvements; and there was a ten percent increase in wages and salaries on July 1, but by then the heart of the community had been splintered.

A brief but major strike was called in 1933 after union organizer Tom Bradley arrived to galvanize disgruntled miners for a newly-formed chapter of the Mine Workers of Canada, affiliated with Workers Unity League of Canada and the Red International Brigade. It was costing the miners more than half of their earnings just to eat. They went on strike on February 1 to demand a 20 percent reduction in their boarding costs, as well as bunkhouse and room rents; and a pay raise of 50 cents per day. The management cleverly asked for a brief cooling off period during which they were able to hastily arrange for a massive influx of police and hastily-hired strongmen to augment the town’s lone police constable. By February 6, the company was saying they had received orders to permanently close the entire facility. The heavily armed militia, sent by the provincial government, further intimidated the workers, 350 of whom gathered at the gymnasium for a conference. Only seven voted to continue the strike. About 320 mostly single men left town on the Prince Rupert and Prince George. The company offered some minimal improvements; and there was a ten percent increase in wages and salaries on July 1, but by then the heart of the community had been splintered.

The town closed in 1935 when copper extraction was no longer sufficiently profitable. The company never paid a penny of compensation for the desecration of the surrounding timber and environment due to twenty years of smelter gases. The poison gases frequently caused sore throats and black dots of sulphur appeared on snow, combustible if touched by the flame from a match. A huge slag pile of black sandy residue is the town’s major landmark, so vast that residents built a nine-hole golf course on it in the 1920s, dubbed the most westerly golf course in the British Empire. According to the town’s Herald newspaper files, cumulatively Anyox accounted for 480 births, 320 deaths and 160 marriages between 1914 and 1935.

Many authors have written about B.C. ghost towns, notably Bill Barlee, Garnet Basque and T.W. Paterson. A brief A-Z summary would have to include Anyox, Blackfoot, Cedar, Eholt, Glacier, Krag, Miocene, Oceanic, Retallack, Sheep Camp, Tachme, Volcanic City, Weneez and Zincton. A similar study of ghost towns and mining camps of Vancouver Island covers Leechtown, Bamberton, Mount Sicker, Cassidy, Morden, Extension, Wellington, Red Gap, Powder Point, Union Bay, Cumberland’s Chinatown, Bevan, Headquarters, Fort Rupert, Cape Scott, Zeballos, Clayoquot, Fort Defiance, Port Hughes, Clo-oose, Kildonan, Hayes Landing, Barclay Townsite and Sechart.

Having served on North Atlantic convoys during World War II, Pete Loudon was a president of the British Columbia Press Gallery and he won five MacMillan Bloedel writing awards. Loudon worked as a reporter and editor in Vancouver, Victoria, Port Alberni and Nanaimo, settling at Hammond Bay, north of Nanaimo. In 1971 he was the editor of a Nanaimo daily newspaper.

Hello,

On or about October 28, 1967, Peter Loudon interviewed Roger Patterson, the maker of the famous Bigfoot (aka Sasquatch) movie, and published the story in the Times Colonist. Can you possibly find that piece in your files and send me a copy?

Many thanks,

Michael Wyman

We happily provide free reference information about B.C. books and authors. It sounds like you need to approach the Times Colonist for the information you seek.